I : AGORA

For some time now, the AGORA has served as the implicit structural model for every legitimate democratic politics.

Historically, the AGORA named the public space in which Greek citizens contested, proposed, and reflected upon political decisions and possibilities. It was located in a physical place, like the Agora of Athens, and citizens congregated there, first, to argue and orate and, later, to buy and sell goods and services. Jean-Pierre Vernant writes:

“The Greeks found themselves with a certain form of social life and a kind of thought that in their own eyes constituted their originality and their superiority to the barbarian world: in place of the king who wielded his omnipotence without control or limit in the privacy of his palace, Greek political life aimed to become the subject of public debate, in the broad daylight of the agora, between citizens who were defined as equals and for whom the state was the common undertaking. In place of the old cosmogonies associated with royal rituals and myths of sovereignty, a new thought sought to base the order of the world on relations of symmetry, equilibrium, and equality among the various elements that made up the cosmos.” (11)

From the structural model of the AGORA (note here that the Ancient Greek word ἀγορά simply refers to “an assembly” or “a coming together”) comes the more contemporary sensibility of the marketplace of ideas, along with all its cognates and derivatives. Implied in this model is the assumption that providing such a space is enough to assure or promote the development of rational, or at least viable, decisional outcomes. Of course, the space the AGORA provides ostensibly imposes constraints or requirements on everyone who enters it. For example, open violence is forbidden in the AGORA, for the presence of undue compulsion disrupts the circulation and free exchange of both goods and ideas. Agon (from the word ἀγών, referring generally to “a competition,” “a contest,” or “a struggle”) must be bloodless in order to function properly here, in order to avoid degenerating into feuds, tricks, and vendettas, or else simply open warfare.

As such, the AGORA is supposed to foment two processes useful for regulating and sustaining a political community in the first place. On the one hand, there is the process of immunization. Displacing conflict into the AGORA is how a political community immunizes itself against (or even just delays) the outbreak of civil war. If you want your fellow citizens to pursue a course of action, then you have to persuade them, rather than force them. In contrast, instead of violence, the AGORA introduces a cross-checking method into the process of political decision-making. By opening up that process and incorporating all the relevant stakeholders, the decision (about whatever) gets cross-checked, refined or revised, and thereby legitimated.

A fundamental assumption here is that passing through the crucible of the AGORA filters or optimizes for fitness. The dysfunctional, or the false, or the undesirable, will be flensed away. Note that fitness can be defined variably here, without any alteration in the function being described. For example, you might argue that exposing a knowledge claim or a practice to robust review necessarily improves its performance (John Dewey, Paul Feyerabend) or its truth quotient (John Stuart Mill, C. S. Peirce, Karl Popper), or that groups of diverse problem solvers typically outperform both high-ability and homogeneous groups.

In this regard, we can see how the structural model of the AGORA undergirds or underwrites the democratic imaginary of what is politically possible. Insofar as democracy gets theorized, or democracy is invoked as the supreme regulatory value of the political, the AGORA provides its conceptual foundation. It serves as the limit horizon beyond which can exist only the writhing dragons of autocracy, tyranny, and violence. Here we can see how the AGORA, and how the agora of ancient Greece, both impose a similar constraint, for the “broad daylight” of the AGORA contrasts markedly with the dark domain of barbarian principles, the enemies of civilization, exotic despots, and nomadic steppe tribes. Despite the superficially wide spectrum of theoretical reframings (consider only a brief typology of democratic modes: deliberative, direct, liberal, procedural, radical, representative, etc.), the basic reference points of the Western democratic imaginary remain relatively invariant.

As such, the structural model of the AGORA can be defined preliminarily as follows: the AGORA is a public space in which stakeholders freely exchange arguments, ideas, and proposals that substantively shape downstream political decisions. Translated into the commonplace language of the democratic imaginary, this means that, in order for democracy to function properly, there must be an accessible public sphere in which citizens can be recognized and/or represented adequately, so as to implement the task of shared popular governance regulated by a common interest. Accordingly, citizens need access to informational channels enabling access to events and facts, which they then can process and refine in the domesticated agonistic space the AGORA at least notionally provides. The AGORA may not guarantee perfect outcomes, but it is supposed to guarantee viable ones. And if outcomes are suboptimal, they can be revised again, even continually, for such agonism iterates. Ostensibly, all that is needed for the AGORA to keep working is for enough, or the right, stakeholders to opt in, accept the minimal constraints, and contribute to its function.

II : AGORAPHOBIA

There is, however, a problem.

The AGORA is a bad structural model – or, at least, it’s a bad model for politics given the realities of political decay. There is a false dichotomy that haunts our thinking, which necessarily opposes the AGORA (in any of its superficially protean forms) to the specter of tyranny. So the story goes, tyranny is always threatening to materialize, and tyranny materializes whenever the AGORA is abandoned, or when it falls into extraordinary disrepair. Accordingly, and purportedly, for so long as the AGORA remains populated by active, vigilant stakeholders, it cannot really fail. It cannot fail because all it requires to do its work is the ceaseless flow of inputs from stakeholders, inputs that optimize and transform simply by means of their circulation and free exchange. Cross-checking always wins. From this perspective, as long as the AGORA exists, it functions like a grand and self-perpetuating alchemical engine, refining the base material of inchoate chatter into ever more optimized forms over time. (You can map any number of live issue areas today onto the structural model provided by the AGORA: the arc of history, free speech, market efficiency, moral progressivism, the raw power of innovation, technological development, the waves of democracy, etc.).

So, why is the AGORA a bad model?

It is a bad model because it can function as described only if a specific set of disruptions never manifest inside the AGORA. Call these disruptions the three pathologies of the AGORA, which are themselves always major drivers or factors of political decay: cacophony, hegemony, and sovereignty. All three terms – perhaps especially the latter two – have complex conceptual genealogies attached to them already (e.g., see Frantz Fanon and Antonio Gramsci on hegemony; see Georges Bataille and Carl Schmitt on sovereignty). That being said, disregard those genealogical attachments for now. Instead, consider the three pathologies of the AGORA as follows:

Cacophony refers to the oversaturation of the AGORA with noise. You can figure noise as abstractly or as concretely as you like. It is the excessive volume of conflicting or random signals that disrupt and overwhelm an agent’s ability to parse and process information. Signals may presuppose background noise, to one degree another (François J. Bonnet, Michel Serres), but too much noise increases signal degradation unto death (aka signal loss). At the very least, it makes identifying or locating a specific signal difficult or even impossible. When cacophony comes to the AGORA, the “free exchange of ideas” stops immediately. Exchange becomes impossible, because the receipt of transmissions is interdicted. Signals can’t be swapped anymore, so the AGORA, effectively, shuts down. In principle, spam disrupts the very possibility of meaningful information exchange by overwhelming agents with noise. Note the core irony here. Cacophony can also be the byproduct of an overexpression of the AGORA’s core function. The AGORA needs a multitude of signals, or voices, but too many signals and everything starts getting noisier a̶̧̼͎͂̆̽́̚n̵͕̿͌̚ḑ̷͊̀̋ ̵̘̃̓̎̽̕n̴̖̪̟̲͚͊ǒ̶̪į̷̖̞̏̚͜͝s̶̺̻͆͗͠i̶͍̗͆̕ę̵̟̹̥͖̊͛̾r̵̲̘̤̙͌́̈́…)

Hegemony refers to the overwhelming domination of the AGORA by a single stakeholder (or group of stakeholders), which self-constitutes the hegemon. Domination by the hegemon entails the effective capture of the medium of propagation itself. Call this controlling the field, or owning the terms of the debate, or stacking the deck, or weaponizing the media (media being conceived here in the broadest possible sense). Under hegemonic conditions, the array of conceptual or discursive options available to a subordinate stakeholder is subject to the controls and directives of the hegemon. When a hegemon captures the AGORA, you could say that it’s as if a cloud of unknowing descends, such that all subordinate stakeholders can make their contestations and submit their proposals only by employing or rearranging the terms imposed upon them by that hegemon. Hegemony obliterates or occludes the inputs the AGORA needs to do its work. Indeed, it transforms those inputs into yet further extensions or even iterations of itself. And note the degree to which the most effective hegemony camouflages itself. The camouflage is useful, even necessary, as the hegemon’s invisibility precludes any meaningful contestation of its power, much less the abrogation of its reach. Fish can’t see water. Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen (whereof one cannot speak, thereof must one be silent): these are truly the magic words of power.

Finally, sovereignty refers to the overconcentration of procedural or regulatory influence that enables direct intervention in the structural composition (the νόμος, or nomos) of the AGORA itself. “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,” an old book says. In other words, the sovereign alone possesses the power to change the “rules,” the rules that process and structure all inputs from other stakeholders. Deciding on what constitutes an exception means deciding when a given rule obtains, or when that rule is to be modified (or suspended, for that matter). When the sovereign comes to the AGORA, the flow of inputs from stakeholders gets redirected, revaluated, or even shut down as if by fiat. Insofar as the structural model of the AGORA presumes to be self-regulating in some capacity, then, a sovereign captures the regulatory apparatus and distorts that apparatus for its own purposes. Sovereignty thereby disrupts the function of the AGORA because it rewrites what is possible and impossible, precisely by virtue of the sovereign intervention.

Notice how each of the three pathologies of the AGORA derives from the overaccumulation of technical debt. Respectively, each pathology refers to the following: too much noise, too much capture, too much intervention. So, technical debt in the AGORA will compound itself forever. Meanwhile, defenses of the AGORA tend to return again and again to the structural model of the AGORA itself. Whenever a pathology gets acknowledged, it is always again the structural model that is invoked in order to correct, ward off, or warn against the pathology in question. (Consider the following analogy: Imagine if your doctor only provided colorful descriptions of health and then proposed such descriptions as the remedies for any sickness afflicting you.) This rapidly leads to an infinite regress – an auto-immunitarian spiral – in which redressing the pathologies of the AGORA requires merely a return to the AGORA, which intensifies the pathologies of the AGORA, which necessitates a return to the AGORA, and so on.

My point is that the three pathologies of the AGORA preclude ultimate resolution inside of the AGORA itself, at least insofar as the pathologies have intensified to such a degree where they genuinely disrupt its ability to function. From the perspective of the AGORA, of course, this observation constitutes a form of apostasy, because it is suspending the AGORA, or departing from it, even temporarily, that ostensibly invites or even guarantees the return to tyranny, the incursion of dangerous and primordial exteriority.

To clarify the role played by the three pathologies of the AGORA, consider this analogy, then: Imagine you’re playing a game. The game has pieces you move about, and the range of possible moves is constrained and produced by the rules. No pieces, no rules, no game. Here are three possible disruptions of the game: (1) The other players scream constantly at such a high volume as to preclude any of your moves. Maybe the other players are oblivious or rude, or maybe it’s a strategic ploy intended to impede your plans. In any case, after a certain duration or intensity of the screaming, the game can no longer proceed. (2) You get no pieces, or you are forbidden from moving, or your moves are even decided by other players. Constraints are necessarily part of every game, of course, but if there are too many constraints, or if they’re imposed too asymmetrically, then any game will founder. (3) Other players get to adjust the rules continually to their benefit and your disbenefit. You always remain obligated by whatever rules currently apply.

Cacophony, hegemony, sovereignty. Faced with any, or all, of these disruptions, what’s a body to do?

III: ARCHIPELAGO

In contrast to the AGORA, we need an alternative structural model of political possibility. Call this alternative model ARCHIPELAGO.

Geographically, an archipelago is a chain of islands that coexist in the same oceanic region. In the most generic sense, an archipelago is just the collective noun for a group of islands. Most archipelagos, however, consist of oceanic islands originating from volcanic activity. They form when volcanoes erupt on the seafloor, close to tectonic plate boundaries. As tectonic plates shift, lava forms mid-ocean ridges, and when parts of these ridges break the surface, volcanic islands emerge. A chain of such islands, also known as an island arc, is the paradigm case of an archipelago.

Abstracting away from the strictly geographical register, we can derive a number of distinct conceptual and speculative features that characterize ARCHIPELAGO as a structural model.

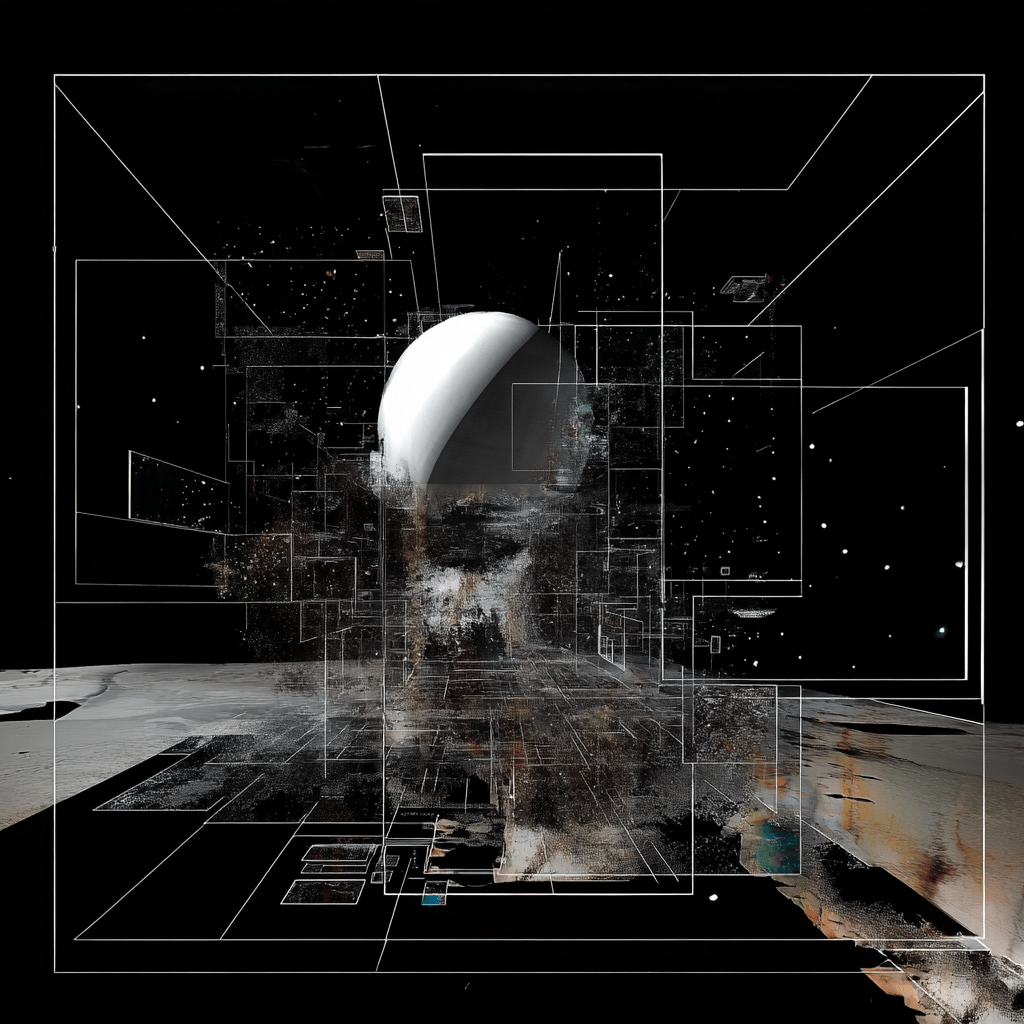

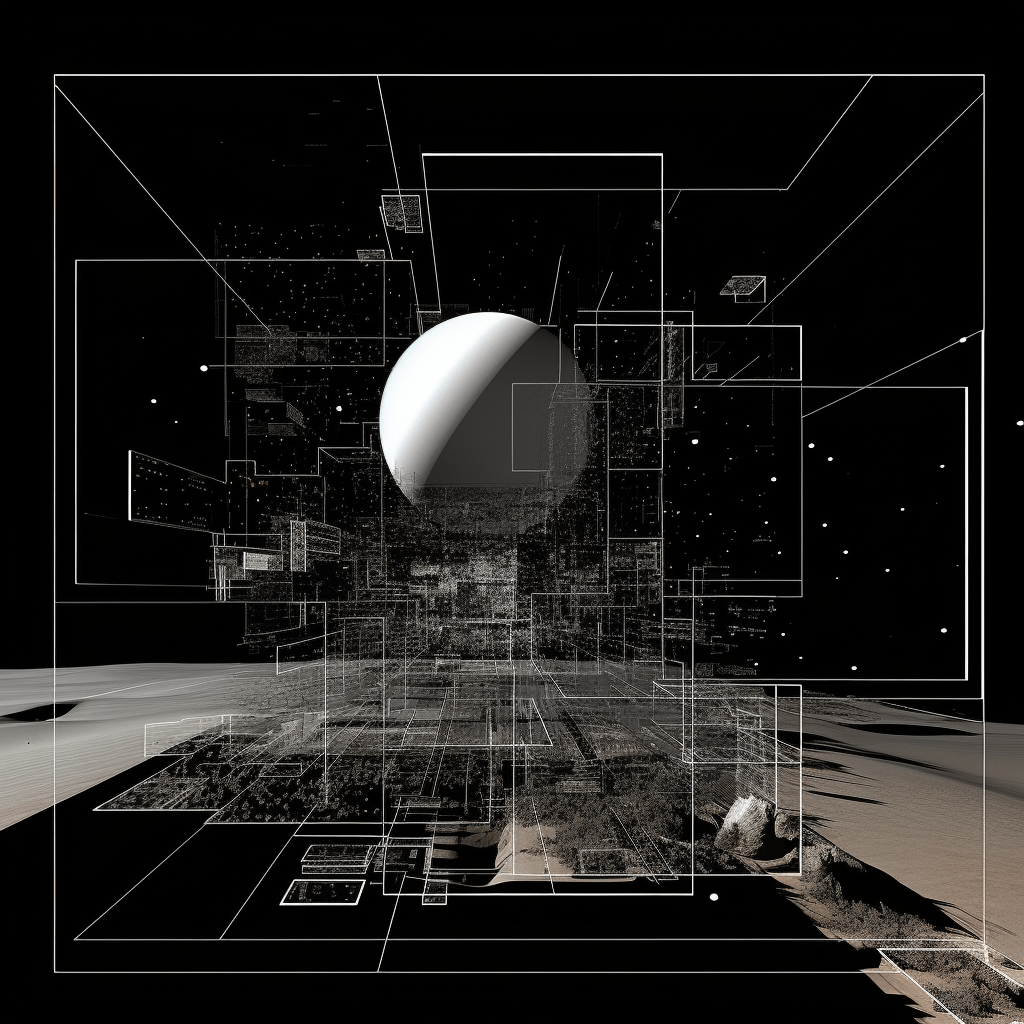

At the uppermost level of the ARCHIPELAGO model, there is the discrete colocation of individual islands. Each island is discrete, that is to say, distinct from every other island in the island arc. The watery passages, or straits, between islands separate them, yes, but, like borders, such passages simultaneously divide and provide sites through which the meaningful circulation of bodies, goods, symbols, and weathers transpires. Water is a fluid boundary, a zone of transit; the seas have depths. Accordingly, the colocation of islands in an archipelago refers to the discontiguous continuity of the island chain or grouping itself. ARCHIPELAGO is a kind of network structure: it is neither merely a coming together of disparate elements, nor the just the background or site for such a coming together. Islands in an archipelago are colocated because they exist in the same locality, as part of the same island arc, but they are also discrete insofar as you need more than one island in order to have an archipelago in the first place.

One level down in the ARCHIPELAGO model, we discover the subterranean mode of association that constitutes the physical structure of the island arc. The discrete quality of individual islands (along with their respective biogeographies, cultures, and microclimates) largely takes place on and around their surface land mass. But there is an occult network beneath the surface of the sea. Leave the marvel-shadowed islands, swim out past the brooding reefs, and dive down through black abysses. Go deeper – slip beneath the obscuring waves – and you will find many-columned Y’ha-nthlei, the secret geological affinities that link all the islands in the archipelago together. Mid-ocean ridges and volcanoes form seafloor mountain ranges, of which the visible surface islands are only peaks. Most of an archipelago (sometimes called the archipelagic apron) is actually submerged. This is what I mean by a subterranean mode of association, then: ARCHIPELAGO is a network, and nodes in the network are linked. Indeed, their linkage is a necessary condition for ARCHIPELAGO in the first place. But the network links between each node are not readily visible. They have been encrypted.

Go even deeper now – take your Iron Mole and penetrate beneath the subaquatic striations of ocean crust – and you will find the geotraumatic origins of every ARCHIPELAGO. As tectonic plates shift, tensional stress fractures the Earth’s lithosphere, resulting in a variety of geological phenomena, from magma activity to seafloor spreading. This is the truth of things: everything visible on the surface of our world is but the jagged remains of its infernal interiority (“the repercussion of a primal Hadean trauma in the material unconscious”). We live among the blackened and scattered bones of the Earth. Directly below your feet at all times, far down below the crust, is the black blazing world that birthed you from its violent womb. Accordingly, high island formation is always the result of geotraumatic activity, and island arcs, or archipelagoes, are the ellipses and traces of that ongoing primal trauma… How does Heraclitus have it? “War is father of all and king of all.” The subterranean mode of association that composes ARCHIPELAGO leads us down to the dramas of the depths, to the shearing tensions and torsions that ultimately produce the world of all visible forms.

Consider here J. G. Ballard’s 1964 short story “The Volcano Dancers.” The story follows Charles Vandervell, a British expatriate living in a house situated on the slopes of an active volcano. The locals have largely evacuated, save for a mendicant “stick-dancer” temporarily living just outside of Vandervell’s house and performing his apotropaisms and venerations to the burning mountain. Vandervell is fascinated by the dancing man, one of the few other humans who remains in the increasingly blasted landscape – and who seems, like Vandervell, to bear an active, if obscure relation to the geotraumatic site that looms increasing visible. Throughout the story, Vandervell announces his search for another volcano enthusiast (or, perhaps, fetishist would be more apt), named Springman. For Springman has already committed himself to the fiery wound, or so it seems: “‘I’m looking for Springman. I think he came here three months ago.’ ‘Where is he? Up in the village?’ ‘I doubt it. He’s probably five thousand miles under our feet, sucked down by the back-pressure. A century from now he’ll come up through Vesuvius.’ ‘I hope not.’ ‘Have you thought of that, though? It’s a wonderful idea.’ […] Cinders hissed in the roof tank, spitting faintly like boiling rain. ‘Think of them, Gloria – Pompeiian matrons, Aztec virgins, bits of old Prometheus himself, they’re raining down on the just and the unjust.’” The story ends as the volcanic activity continues to intensify, approaching a full-fledged magmatic eruption, and Vandervell’s companion, Gloria, discovers him absent. Fire licks at the rim of the crater. Even the volcano dances.

Define the structural model of ARCHIPELAGO like this, then.

ARCHIPELAGO is a discontiguous network space, neither public nor private, and it is populated by discrete stakeholders (or groups of stakeholders) in variable and various conditions of colocation, stakeholders whose modes of association are subterranean yet manifold.

(Recall here Herbert A. Simon’s parable of the two watchmakers. Lovisa Sundin summarizes Simon’s concept of “near-decomposability” like this: “Imagine two watchmakers constructing equally complex watches that each consist of 1,000 elementary units. One watchmaker constructs his so that if he had assembled some parts and then was disturbed the watch would fall into pieces and would have to be reassembled from scratch. As a result, he quickly runs out of business. The other watchmaker organizes his watch into stable subassemblies of ten parts each, to make up a super-assembly of ten, and so on. If he is disturbed, the watch would fall back on the last intermediate subassembly level. His work loss is therefore smaller by orders of magnitude. Needless to say, he prospered. The gist is that systems analyzable into successive sets of subsystems evolve more rapidly than non-hierarchic systems, because the time it takes to achieve complexity depends on the number of potential intermediates. In the survival of the stable, only hierarchies have time to evolve.”)

Underlying or even producing every ARCHIPELAGO is the shifting inorganic lifeworld of geotrauma. There is therefore an ineradicable instability or unruliness lurking underneath the very foundations. This fact is ineluctable; you could say the very pillars of the earth are magmatic flows. So, nothing can be fully secured – at least not forever – but this very unruliness in fact gives rise to all islands and to every ARCHIPELAGO. Indeed, it gives rise to the continents themselves, to all their dramas, hordes, and ruins.

Contrast the latent, productive, and even violent instability of ARCHIPELAGO with the instability of then AGORA, which cannot presuppose the exclusion of cacophony, hegemony, or sovereignty, but rather only falters whenever these disruptions and pathologies manifest and make their leprous, regal faces known to the crowd. Where the AGORA falters, ARCHIPELAGO enables the projection of political force. It does so precisely on the basis of complex, partial, and shifting dynamics of occlusion, association, and formation.

In other words, the ARCHIPELAGO dances.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Michael Uhall is a political theorist at Indiana University East. He works on ecopessimism, geopolitics, philosophical anthropology, psychogeography, and the politics of outer space. His academic and nonfiction work appears in 3:AM Magazine, Contemporary Political Theory, Nature and Culture, Rhizomes, SYNTHETIC ZERØ, Utopia District, and Vault of Culture. His first book, Noir Materialism: Freedom and Obligation in Political Ecology, is now available from Rowman & Littlefield. His second book, Theory of the Alien: Astropolitics, Spacepower, and the Outside, is forthcoming from Routledge. Other projects under development include a philosophical study of CIA counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton.