邊界_RG works at the edge of language, memory, and machine cognition. Their collaboration explores the aesthetics of the recursive interplay between generative systems, speculative design, experimental essays, and posthuman modes of communication. Through installation, video, performance, and AI-mediated feedback, they construct evolving symbolic infrastructures that reframe subjectivity, authorship, perception, and attention. (https://bianjie.systems/)

Interview 001

Ian Margo & Alexandre Montserrat

DIFFRACTIONS: Can you speak to the genesis of 邊界_RG (Biānjiè Research Group) as an artist collective? The focal point of the research group dovetails a number of threads: interface studies, memory architectures, and distributed epistemologies. How are some of these focuses translating into your personal and collaborative theoretical and artistic endeavors?

[邊界_RG]: The 邊界_RG project began only a few months ago, at the beginning of the summer of 2025, in the final days following a long stay in San Francisco. Our objective was clear, and it arose in contrast to—and out of the need for—a very specific context: Which spaces are truly engaging with the contemporaneity of theory within an artistic practice that is responsible with its own mediums? What is the right environment for establishing the possible within practices that operate with knowledge and aesthetics? What are the means, and how can we generate an open system that allows us to avoid falling into “the format” while still continuing to experiment? Our initiative stems from a need for contemporaneity but also from the search for and construction of a cultural context that is coherent with a set of needs we see as implicit in artistic and cultural production. 邊界_RG started from a simple commitment that echoes Flusser.

We began as a production theory put into practice. Once you theorize the production process, intuition and heuristic experiments don’t get diluted, they finally unfold to their full extent. So we set up a studio model where theory, observation, and experiment circulate as one pipeline. That’s what “artist collective” means for us. This is a space for discussion and experimentation, a procedure for making creativity reproducible and legible in public.

DIFF: Could you speak specifically about some of the other members and their research within the group? You describe 邊界_RG as approaching research as a public-facing practice that takes shape through writing, curation, dialogue, production, and design. How do these activities connect to the broader themes of artificialization and technological mediation that the group engages with?

[邊界_RG]: As artists, we work with materials, which we could consider not only a form of research in itself (in the case of the artist, focused specifically on aesthetic exploration and experimentation through said materials), but also as a form of production, relocation, and exchange of signs. In this sense, research and production, as we understand it from 邊界_RG, necessarily has an economic potential. Operating with materials is, then, to break down the given into a specific body of extracted possibilities; it is to start from (and return to) an open framework where the materials appear as a ground or context (social, cultural, political, linguistic, geographical, etc.). This entire mobile landscape, this recursion in the materials, is part of systems of mediations or what we could understand as techniques or processes of artificialisation. We would then understand processes of artificialisation as a process of representation (what is represented / the word / the grammar/ the structure / the discourse / the geometric / the whole and to what extent it is a whole).

Artificialisation is inherently technical, and both are necessary in both cultural production and research processes. Within 邊界_RG, each member’s practice demonstrates how different modalities of artificialisation operate as both research methodology and cultural intervention. The technical dimension operates not as an external tool applied to materials, but as the very condition through which materials become available for manipulation, extraction, and recombination. Every gesture of breaking down what is given into extracted possibilities requires technical procedures, protocols for selection, frames for legibility, and systems for storage and retrieval.

The act of making materials appear “as ground or context” is itself a technical operation that transforms raw encounter into workable substrate. This technical necessity extends beyond digital or mechanical apparatus. Language itself operates as a technical system of artificialisation, i.e: grammar functions as a processing protocol, discourse as an organizational schema, and signification as a procedure for converting material encounters into exchangeable signs. When we operate with materials recursively, we are always already operating within technical mediations that determine what can appear, how it can be extracted, and what forms of recombination become possible. Cultural production and research thus cannot be separated from their technical conditions precisely because both involve the systematic transformation of encounter into artifact, experience into object, and process into product. The “economic potential” emerges not despite this technical dimension but because of it. Value is generated through the technical capacity to extract, process, and reconfigure materials across different registers of representation.

Research becomes a form of technical memory that archives not just results but procedures, making visible the apparatus through which knowledge is produced rather than simply the knowledge-objects that result. In this sense, artificialisation operates as the underlying technical condition that makes both research and cultural production possible while simultaneously being their primary object of investigation. We study artificialisation through artificialization and investigate technical mediation by means of technical mediation. The recursive structure is not incidental. It is constitutive, we believe it reveals how technical systems don’t simply mediate between subjects and objects but generate the very distinction (the limit) between mediated and immediate that organises contemporary experience.

DIFF: [Ian Margo] In Bunker-Tool, you describe a navigable environment of chambers housing abstract technological agents and abstract machines, broken faces where “the figure is the figure of the ground, and the ground is the ground of the figure.” This situates the bunker-tool as an artefact with infectious, apparatus-like potentiality. The Wet Box, by contrast, has been described as “a recursive linguistic exploration of objects in the digital age.” How do you see these two constructs, the bunker-tool and the wet box operating in relation to one another, and what kinds of contagion or agency (if we could use that term) do they enact as artefacts?

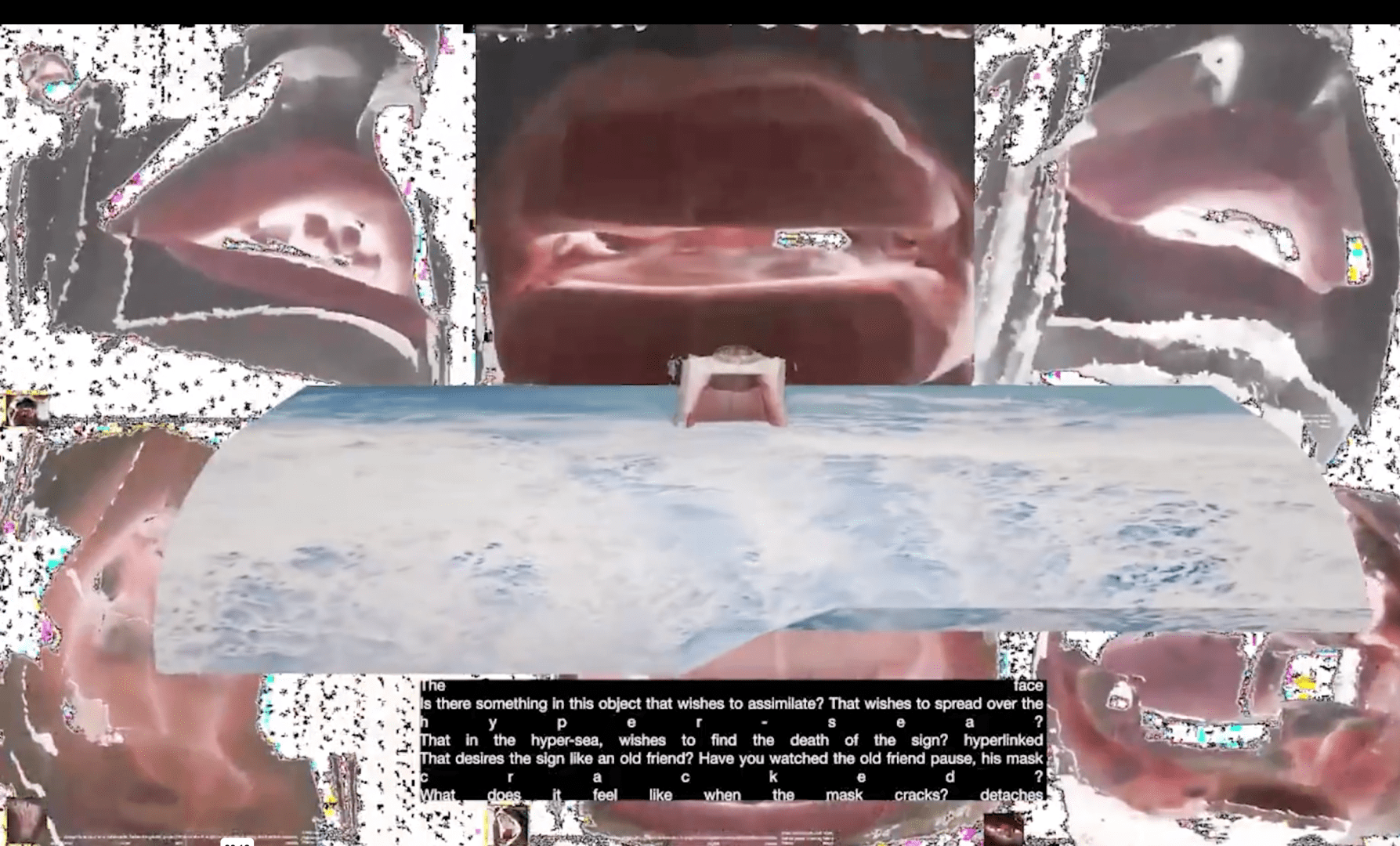

[IAN MARGO] : Actually, the Bunker-Tool and the wet box are completely related projects. Over the summer of 2024, I developed this experimental game together with Levi Yitzhak. The first prototype, which branched off into several projects, was what we called Bunker-Tool Game. The game depicted a series of partially enclosed, interconnected chambers. Some chambers had uneven floors, columns, and wide spaces. While moving through the environment, the user could encounter certain items. We called them “pieces.” The game was simple: the interaction allowed each piece to be carried and assembled with others, as well as to alter a nametag attached to it that was visible even through walls (language as what detaches, what is shed). This made possible several games at once: not only could one assemble complex technical bodies of confusing appearance (appearance toward abstraction), but one could also signify them as linguistic bodies based on text blocks.

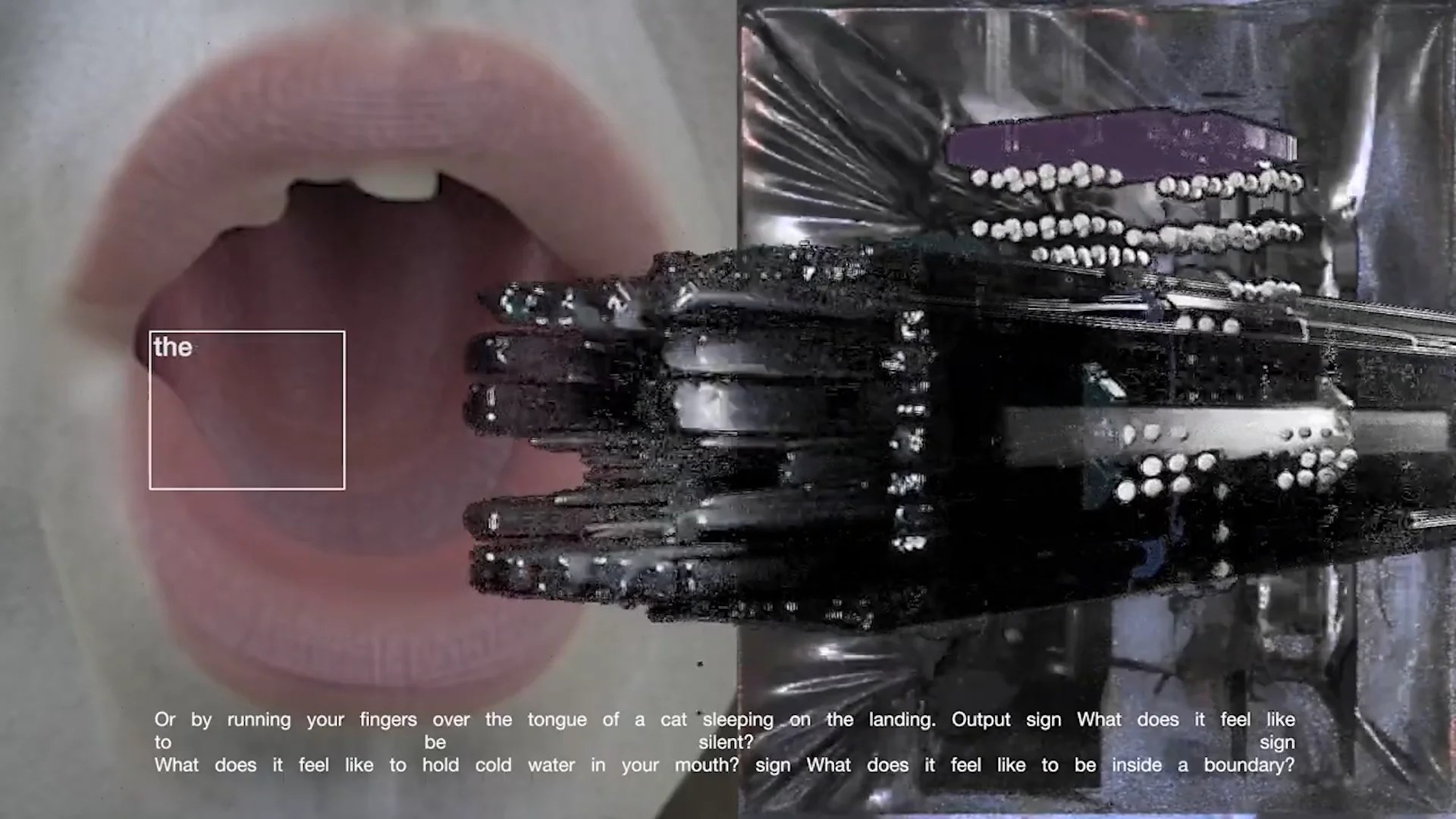

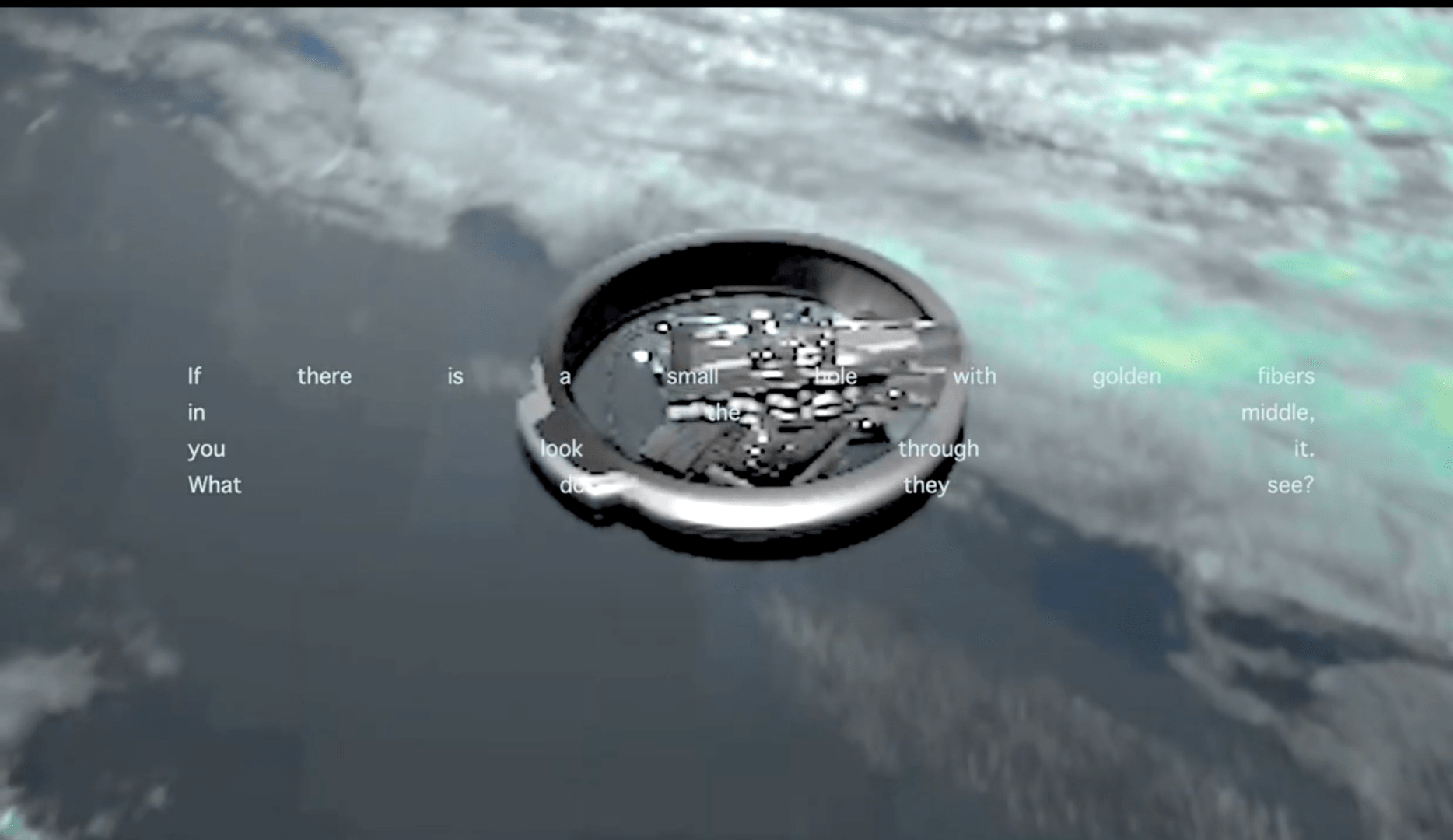

This game eventually changed after deep research into abstraction and faciality to a new version where the pieces had been replaced by masks, two hands, and a sphinx. A dark chamber was also added, where, through the walls, one could only read the text of the blocks attached to each item. The assemblage here was a mask-complex, a cult of embodiment (the content requires a body / what is given is proposed by a representational system / what is presented is presupposed). The wet box emerged shortly after, through a series of readings that sought to work through abstraction, interaction, systems, language, medium, and technology. (The system tends toward the object / the possible is what is contained, the potential is what is shed / the contained that sheds itself). At first, the wet box focused on forms of limit, on the frame, what it attempted to grasp as closest to the non-representational.

One could say that the theoretical investigation behind Bunker-Tool and the production of some of its graphic elements were later reused to assemble the wet box. Practically speaking, the wet box is a flight, a tension (the tense system) toward a limit or frame. This appears as the center of discourse, on the basis that it is impossible to escape this limit, the limit of representation. From this, something is shed (is produced), that is, a space is reconfigured, and language is reactivated. The wet box, then, seeks not only to represent that activation but also to integrate into its form the gap that would allow such activation to occur. Of course, insofar as we begin from a series of mediations, whatever is mediated will be represented. We cannot access any kind of “before” of the sign, even if we operate with the limit.

The Bunker-Tool, which resurfaces within the project d/wb (desert/wet box) as a series of speculative texts I wrote while developing the wet box and its series (which also includes third extension and fieldware), is a similar exercise in the production of signification through the presentation of tokens, repetitions, and abstractions. Signifier without signified, as my friend Marcos Parajua would say, or what happens when we separate figure from ground, and to what extent this is possible. It is here that we could speak of the object in its totality and in its absolute closure (a moment in time / the infinity of an instant / it contains all its possibilities, therefore it is impossible). That which detaches from “its” ground, and here “its” already posits a directionality; again we are mediating what detaches, granting it a potentiality and a reduced series of possibilities that are certain values produced out of the object’s absolute instability. The object is no longer an object but the thing activated or, let us say, the objective, the target, that operates and with which we can operate.

DIFF: Another key thread in the group’s work seems to center on biomes—particularly the desert. How do these biome-specific imaginaries, and the desert in particular, shape or animate the works at hand? I’m thinking here of pieces like Design in Rising Winds by Flora Weil, which engages with geoengineering imaginaries and draws on Jerry Zee’s insight into how desert winds can “create experimental worlds.”

[邊界_RG]: We work with “biomes” as scale tools that force our research to stay planetary in scope while remaining locally legible. Treating “environment” and “field” as a design parameter forces us to ask how an interface, a memory system, or a protocol behaves when it’s situated somewhere specific rather than abstracted from place. You see this in Flora Weil’s Design in Rising Winds, which looks at ecologies reshaped by Chinese geoengineering and ties planetary infrastructure to lived perception, an explicit exercise in translating the global into the local without collapsing either side. And in Ian’s desert/wet box, a technolinguistic program that explores navigation beyond vision, the “desert” operates as a condition for testing abstraction and interface, with the video work of the wet box staging those dynamics in public form. The biome is the field; the desert is a vast backdrop. The biome operates as an extension with certain entities and objectives that are presented as given, requiring activation. Information can never be given. In the desert, what is given is liminal; it easily detaches as appearance, as horizon, as edge (hence 邊界—boundary—).

Ultimately, the desert is easily framed, and its frontier always emerges detached from its surface, defining itself against the backdrop that is vast and clear. Nothing ever fully falls upon the desert’s surface. This matters to us because it defines not only the pretext of 邊界_RG but also because, in the end, we always work framed and detached. It is in the desert where abstractions present themselves; upon its extension the sign casts its shadow.

Ultimately, biomes help us calibrate scale. They let us design and theorise at planetary resolution while producing rigorously site-aware and, of course, desert-included, but also what it’s detached from. I think another fascinating dimension your research group brings to the fore is its focus on infrastructure and intelligence, whereby artificial intelligence comes to morph into artificial experience.

DIFF: As the essay by William Morgan spells out, artificial experience does not refer to just any technologically mediated interaction; it is precisely the kind of experience that is uniquely enabled by AI’s infrastructural properties. I would be interested in following up on this essay if AI systems genuinely co-produce experiences with us, to what extent does this grant them a form of agency in shaping those experiences? Moreover, might that agency signal a shift toward entirely new paradigms of causality, beyond human-centric models of authorship and intentionality?

[邊界_RG] : On agency, in that frame. We wouldn’t grant today’s systems agency in the thick, intentional sense… What they do have is operative agency, a kind of capacity to shape conditions of action. They set defaults, propose trajectories, pace interactions, and filter our perception. If you can change what’s available, when, and with what salience, you then start co-producing experience. That’s real causal influence even if it isn’t human-style intention.

William even cites work forecasting AX design arising because models now occupy a new ontological space with “vast social agency” not because they necessarily “intend,” but because infrastructure that patterns attention and timing is causally potent. On causality. Well… We would say, a need to start thinking musically. The unit of cause shifts from a single author to a composition. As in data pipelines, model policies, interfaces, and users in feedback.

Causation becomes distributed and procedural… Swap the training corpus, the reward model, or the interface cadence, and you measurably alter outcomes. So authorship gives way to configuration: who specifies objectives, guardrails, latency budgets, and override paths is, functionally, the “author.” Well… if AX is the layer, then our responsibility sits at the configuration level. The test, perhaps, is not “does the user witness intelligence?” but “did the configuration yield a better encounter-on-contact?”

DIFF: Finally, to [Alexandre Montserrat]: If, as you suggest, the A-Subject emerges as the operational self-recognition of technical memory—its doubled existence as both querying process and archived object—does this dissolution of the “site” of memory into pure process also signal the disappearance of the very temporal rupture that once defined historical consciousness? And if so, are we moving toward a condition where the distinction between remembering and predicting collapses into a single, recursive operation?

[ALEXANDRE MONTSERRAT]: From the outset, classical historical consciousness was tethered to experienced discontinuity… It hinged on… felt breaks. Visceral moments when the present recognised itself as divergent from what preceded it. The dissolution of memory’s “site” into pure process doesn’t eliminate the “temporal rupture” you speak of, rather it transforms this “rupture” from a “historical” event into a permanent architectural condition. The “break with the past” that Nora identified becomes encoded as technical memory’s basic protocol: an exception that constitutes rather than suspends the system’s normative operation. And by “technical memory”, what I mean is exteriorised, machine-operable retention. At that layer, the system does not aim to distinguish, nor does it respect our temporal modalities. Its operational logic treats all data, past traces, present inputs, and future probabilities, as equivalent objects for identical processing schemas. Again, the system can only aggregate and correlate across a flattened continuum.

With the “A-Subject”, it isn’t “becoming” so much as being continuously recomposed. It’s trapped in this encounter with its own perfectly preserved corpse. It confronts its own archived past as discrete data-objects that resist narrative suture. The “subject” processes loss without the temporal distance grief requires. The archive does not wait. On remembering and predicting, the tension here is that we’re not moving toward a single recursive operation so much as discovering that recursivity was always the upstream condition of what we conceived as linear historical time. The mausoleum architecture – which Part II will articulate – materialises as the spatial embedding of this temporal compression, where memory becomes a pure process precisely through becoming pure preservation. The system doesn’t distinguish between these because its architecture of total retention creates a compression where all moments become equally present, equally accessible.