This interview is conducted with Mike Hill about his book On Posthuman War Computation and Military Violence.

Mike Hill’s On Posthuman War reveals how demography, anthropology, and neuroscience have intertwined since 9/11 amid the “Revolution in Military Affairs.” Beginning with the author’s personal experience training with U.S. Marine recruits at Parris Island, Hill gleans insights from realist philosophy, the new materialism, and computational theory to show how the human being, per se, has been reconstituted from neutral citizen to unwitting combatant. As evident in the call for “bullets, beans, and data,” whatever can be parted out, counted, and reassembled can become war materiel. Hill shows how visible and invisible wars within identity, community, and cognition shift public-sphere activities, like racial identification, group organization, and even thought itself, in the direction of war. This shift has weaponized social activities against the very notion of society.

Mike Hill is a professor of English at the University at Albany, State University of New York. He is the author of After Whiteness: Unmaking an American Majority and coauthor of The Other Adam Smith.

DIFFRACTIONS: Can you reflect upon what were some formative moments or interests that catalyzed your intellectual trajectory. Specifically, I’m interested in your book On Posthuman War, which draws from multiple fields and philosophers. What compelled you to embark on writing this book, and can you spell out the influences that converge in your work?

MIKE HILL: With all due modesty, I can’t help picturing Walter Benjamin’s famous passage on “Angel of History,” the concept he derived from Paul Klee’s painting, “Angelus Novus.” I’m sure you know this image and Benjamin’s thesis. The angel is transfixed by a terrible pile of events, an explosion whose maelstrom propels him backwards toward a future neither we nor the angel can see. Because the angel’s eyes are fixed on the rubble, s/he has no place from on high to connect the catastrophe of history (“what we call progress”), the tumultuous present, and whatever it is that might lie ahead. The past is an event leading the angel to not-even-God-knows where. It’s a scene neither of stasis nor teleology. But maybe, unlike Benjamin, I think the past can be sorted out.

I guess there comes a time in an academic career – and I may be one of the most unlikely people to have had one – where enough writing has piled up that you find yourself blown forward in a way that something like Benjamin’s thesis on history. When I think of the formative moments that played a hand in creating my pile, not to mention how I think about the pile itself, there’s a strange but also a familiar feeling. It’s a lot like having to move forward with linkages you’re forced to make but don’t control. Looking back at the catalyzation of my intellectual trajectory – as you put it – feels like being a miniaturized version of Benjamin’s roughed-up messenger.

Seriously though, I suppose anybody in the humanities coming out of my generation of training, which was the heyday of theory in the early 1990s, is bound to have entered the profession while receiving some moderate burns. Not only did many of those theories fail to deliver angelically – I mean, as in providing a road map for knowing more and acting better – the cumulative effect of what I mostly studied in graduate school was formative by default. We lived a minor version of the trauma we were theorizing.

Disciplinary eclecticism was the order of the day during the time I completed my doctoral degree. For me, at a middle-ranked publicly funded state university, albeit a Research 1 school, there was a sense of exhilarating, almost boundless freedom. One of my former professors describes the moment in retrospect as what people must feel like when they base jump with a bungee cord. There was this notion in the 1990s that anything goes and that everything was up for grabs. All you had to do was jump and start grabbing. But as every bungee-jumper knows, the thrill of falling is that there’s nothing to hold on to. You start off thrilled, but you end up hoping like hell somebody will pull you back to solid ground.

Then there’s that crucial instance every bungee jumper prays for: The elastic tether grabs you by the ankles like you’re being born and as it recoils, you hang there helplessly and bounce. I bet nobody really enjoys the bounce, or if they do, they know each bounce is less enjoyable each time you fail to go all the way up. It’s not a trajectory, anyway. And for some bungee jumpers, there are major complications. The way back ends badly for some, as ways back sometimes do, with a terrible blow. It’s as if the tether gets stretched too far, and what was supposed to be the safety of the base ends up being the superstructure that smacks you on the head. In any case, whether you stay suspended, get smacked, or make it back to the base like me, I don’t think any account of doctoral studies in the Humanities can leave out the bungee scenario. It’s hard to tell my students to keep jumping. But I’m grateful they still do.

Luckily, after getting my terminal degree, I happened to land at a fully-funded (not so now) Humanities Institute with a 5th year of graduate funding. This helped me keep writing. There and throughout my course of study, I read extensively in materialist theory and philosophy. This has grounded the way I’ve approached newer material. Additionally, I was able to take courses in continental philosophy outside the English Ph.D. program. In my philosophy coursework, the bungee cords were secured at exhilarating heights. We got to study with some big-name philosophers and engage with them one-on-one. Some courses in feminist psychoanalysis were also wonderfully generative and challenging. Cultural Studies, my personal attachment to the base, provided license to do what was until the 1990s unthinkable: seek employment in an English department without writing much on literature (though I teach and like reading it, and write on it more now that literature is leaving the academy). My doctoral training also included serious historical work on the British and French Enlightenment and its economic, philosophical, and literary aspects.

I never published anything from my dissertation, which was on print technology, the novel, and the eighteenth-century crowd, with a strong Foucauldian bend. Instead of staying with the eighteenth century, I leapt onto a bandwagon-in-the-making and produced two books on – of all things – whiteness. I can still hear my dissertation director warning against that move. “Congratulations on your book contracts, but now you must write them. “Don’t jump!”

External to reading an academic context, I’ve always been connected personally and intellectually to working-class issues, and I suppose to identity questions – I mean by that, the ways interpellation works in the Althusserian sense: How identities are called into existence in ways that may or may not work out in the best interest of the person being identified. I’ve also been drawn to the more affirmative flipside of that. I’ve tried to identify various points in history where the interpellative apparatus becomes fragile, which can happen in dramatic and not altogether comfortable ways. If you can hang on and not panic, even the most restrictive forms of interpellation can eventually make room for alternate ontological states. This kind of prospect interests me most.

A key breakthrough for me closer to On Posthuman War comes from adding to my reading in political economy a lot of recent texts from what’s getting called today political ecology. To think further back about After Whiteness, I see can see better now how this book was an attempt to explain something essential about classification, time, and scale – which puts creative pressure on the powerful historical fiction called the white race. But in that book, I also focus on categories of knowledge, as in disciplinary divisions. You can see this in the way On Posthuman War is divided into three parts, moving in a quite purposeful way from demography to anthropology to neuroscience, in that order. I think After Whiteness has in common with the war book that it was performing what I was also trying to explain. Its disciplinary promiscuousness was an organic extension of the way I was trying to expound upon transformations of categorical belonging: The book is as whiteness does.

In a way – and I haven’t thought about this until now, being forced, as we were saying to look back – After Whiteness was a suitable prequel to On Posthuman War. I’m accused very often of being “all over the place” with my research – like Crusoe, maybe adrift in some way, a big no-no for having a good academic career. It’s true I spent my graduate school years writing on the history of novels and riots, then jumping to whiteness, then to the Adam Smith book, and then – heaven forbid – posthuman war, whatever that is! But there’s that triad I mentioned before, the category-scale-time connection. It’s central to all this work, both thematically and in the way I have changed as an academic researcher.

When Whiteness: A Critical Reader came out in 1997, white identity as a topic of scholarly inquiry simply did not exist. The scale of research on whiteness was effectively zero. But as work on the topic amassed, a sub-discipline grew. A formerly invisible racial identity – the so-called normal one – was at least rendered knowable to and by those who at least nominally had it.

There was a special issue of the minnesota review, “The White Issue,” that appeared in 1995, a couple years before the Whiteness reader. In labor history, there were some very good analyses of white labor power following Du Bois’s directive. This work was important and essential. But only after a spate of books and articles on whiteness had appeared was there a larger interest in going back to that white labor history. More importantly, the record was finally set straight that black and other minority writers had for a very long time been on to the shape-shifting ruses of whiteness. New things have a way of reorienting what comes before. We should remember Baldwin: “As long as you think you are white, there is no hope for you.” That’s a hopeful statement, even if it’s put in a “no hope” kind of way.

Just as this awareness about whiteness as a research problem was emerging, that is, just as the goliath was taking shape such that we Davids might dare to step up with black scholars in the lead and face it, announcements ranged far-and-wide about the disappearance of the white race, or at least, the fading out of its predominant historical form. This is a kind of irony prone to all forms of classification: Once you think you’ve named a thing, it’s already changing into something else. As explained at the end of After Whiteness, the historically elusive thing we finally seemed to get a handle on was about to disappear again. This is how categories work in relation to numbers and how numbers change over time. Eventually, numbers trump category.

In the case of whiteness in the US, and here we can finally bring our focus to On Posthuman War, the oft-proclaimed loss of the American racial majority and the rise of domestic political violence could not be more agonizingly clear: The word “again” in the slogan “Make [X or Y] Great Again” seeks a form of repetition that’s actually a form of cancelation. The slogan (which originated in the Reagan era) secretly recognizes the non-existing nature of the thing we’re supposed to repeat. The way I would put this is that a “greatness” of value has been overrun by a “greatness” of scale. Quantitative reality trumps qualitative desire, as I said. Numbers do what identity forbids.

I suspect demography is why right-wing politicians in the US – now more than ever – measure their relevance in terms of crowd size. It’s a numbers game. Mass gatherings replace communicative reason, and shouting is the rule. And what sounds like a declaration in the “greatness” slogan is rather an admission that one form or social organization – the liberal, parliamentary, or normative one – is giving way to something on the order of the mob. Historically, this means civil war and/or authoritarian rule. But crazy moments also afford better kinds of change.

And by better kinds of change, I don’t imagine getting back to a former peaceable time where civil society reigned securely in its oddly reign-less way. In the US, the ideal of liberal norms has never been far from political violence. Remember, there are an estimated 500 million guns in the US – no one really knows how many – and mass shootings have been a regular occurrence. If you put a hand in every American civilian adult, and they decided to rebel, you’d be looking at the 7th or 8th largest army in the world. Immigration control is now called a war effort here. Troops are deployed in US cities in the name of upholding the law – a questionably legal move by the Presidency. The Department of Defense becomes the Department of war, and so forth.

To bring Hobbes in terms of somebody like Agamben, the state of emergency is the only normative state we in the US now have. We may have always had it. In the days of so-called whiteness studies, white nationalist militias were popping up all over the place. From Robert Bly’s Iron John thing to the twenty-first-century manosphere movement of Men Going Their Own Way, white masculinity seems at times to wobble aimlessly, then snap into highly aggressive states. On the one hand, you had the soft rituals of multicultural masculinity ritualized by the once massively popular Christian men’s group, the Promise Keepers; and on the other hand, you had The Turner Diaries, whose race war fantasies were proffered by neofascist groups like the National Alliance and American Renaissance. Remember, the Diaries fiction was made fatally real by Timothy McVeigh in Oklahoma, which was 1995. This predates all the internet bro-casters giving right-wing politicians a boost in the US today.

I’ve mingled with many of these groups – and spent some difficult days on Parris island with the US Marine Corps – to try to experience that white masculine wobbling, agitation, and aggression firsthand. As I tried to explain in After Whiteness, radical shifts in how we quantify racial difference are as likely to cause political panic as they are to become a fetish for moral redemption. But both extremes of panic and redemption seem to go very closely together. Who knew that after whiteness comes the Trumposphere? Maybe we all knew, which doubles the power of historical catastrophe. It feels awful, looking back on the time of After Whiteness, to have seen – and yet not quite seen – that the Trumposcene was already piling up its political wreckage. No wonder the eyes of Klee’s angel look like they’re seeing something familiar and yet totally abject.

Just yesterday we heard the US Secretary of War ask military leaders to intensify their commitment to “lethality.” At the same meeting, the President insists war fighters should be ready to “quell domestic disturbances” – to combat what he constantly refers to as “the enemy within.” And just today, we see the same administration re-awarding 20 Medals of honor to US 7th Cavalry soldiers who fought at Wounded Knee. Does this mean that there’s valor in genocide? I’m afraid it’s worse than that, if only because now everyone is potentially a military adversary. The state has started the military occupation of itself. Now the Ghost Dance is democracy. To speak in opposition to dominant political ideology – a right and a civic duty – is to risk becoming an enemy of state.

DIFF: Arguably, war has always been post-human, not only due to the nature of prosthesis whether tools and technologies, but in the way it mobilizes systems, abstractions, and impersonal logics that exceed the human subject. Could you elaborate on how you define or characterize the “post-human” in your work, particularly in relation to its emergence within paradigms like netcentrism? “all domain warfare,” “a new reliance on data, which allows the joining of subjects and objects in more open-ended and inter-penetrating ways.”

Part and parcel of Netcentric warfare’s doctrine has been positioned around linking soldiers, sensors, vehicles, drones, satellites, and now the increasing role of perception and decision-making distributed to inhuman agents. How do you see this intersecting with concepts like sympoiesis, which foregrounds distributed, co-creative systems of agency? Additionally, theorists such as Nandita Biswas Mellamphy have introduced the idea of larval warfare – suggesting a shift in how war is waged and perceived, particularly as it diffuses into psychological operations, algorithmic governance, and platforms like social media (as Trevor Paglen and others have noted). Given these transformations, do you think the category of “war” itself requires redefinition? Is there still a clear boundary between warfare and other forms of communicative, infrastructural, or informational conflict?

MH: Yes, this is true. War has always been posthuman. The human being has never been itself alone. If you look at the anthropological history of the human being – which is different than my juridical interest in the concept of humanity, which goes only as far back as the Enlightenment – you’d find something counterintuitive but altogether essential: The tools used by homo sapiens predate the origin of the species. Tools invented us, not the other way around. This is not to mention the scientific move away from skeletal-based research toward genomic mapping. Genetic research has both broadened and complicated the history of the human being, now best described as a mosaic of other species, than a class in and of itself. Almost all non-African humans carry 1 to 3 percent Neanderthal genes.[1] Around 80,000-100,000 years ago, modern humans interbred with other hominin groups, including Neanderthals, Denisovans, and possibly “ghost lineages” of archaic humans [2].

But back to tools and technologies, or as you say, prosthetics, these are a defining feature of a human being. They also mark the inadequacy of its classification as simply or purely human in the first place. Everyone knows – or should know – non-human animals also use tools. Chimps and parrots use sticks. Whales use bubbles. Octopi use coconut shells. Elephants use branches (as weapons, even). Orangutans make whistles, and so on. Do spiders count? If we used tools as a defining attribute of humanity, we’d see ourselves as more integrated with the outside world. It’s an ironic thing about how much closer to reality artificial instruments get us; but again, it’s consistent with the good results you can get by emphasizing “doing” over “being,” as we said before.

More directly to your point, I think Steigler was right in insisting that the most stubborn bugbear in Western philosophy is neither ontological difference nor epistemic uncertainty but instead the division we’ve carried forth from antiquity between techne and bios. You’ll remember how adamant Kant was that we must never regard the human being from the “realm of means.” He insists we use the categorical imperative to enlarge our conception of humanity as an elusive moral goal. But we must do this from within the “realm of ends.” The human being must never be identified in the same way technologies are. Contrast this with what neuroscience says about the computational nature of the brain or what Turing and von Neuman detected about the physical universe as a form of computation. No wonder Žižek is taking up quantum physics! No wonder botanists are putting isotopes in root systems to reveal how mycorrhizal networks work as information systems – the Wood Wide Web!

Against the network of things – which are not that different from ecological or neural networks – some still insist that human-to-human intersubjectivity is all that’s required for achieving a peaceful form of international cosmopolitan order. Given the rise of AI, most academics I know are running back to a version of the human being that was never actually there. (Sounds familiar, right?) Today, cosmopolitan in the liberal sense seems as dreamy as Kant’s call for “perpetual peace.” But remember, the title of Kant’s essay by that name is taken from a sign picturing two skeletons dancing over a Dutch innkeeper’s door.

Thinking about this Kantian irony a bit more, I can’t help putting another image out there, and it fits in compatibly with Benjamin’s interpretation of Klee’s angel. As I recall, in Klee’s painting the angel has no arms, just wings, which is maybe the real problem with being blown toward the future that’s in fact ironically behind you. The angel hasn’t got a chance. We need to add to Klee’s image whatever tool the angel of history might likely be holding. But wings can’t hold tools. Divinity presumes the world is as God made it. This is why better futures aren’t in the picture.

I’m thinking here of the scene in Kubrick’s 1968 epic film, one of my favorites, 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the film’s prefatory sequence, called by critics “The Dawn of Man,” raging quasi-human primitives are ripping each other to shreds. They’ve reached a stalemate. Suddenly, one of them, beating the ground in a fit of rage, seems to realize in the mayhem, “I’ve made a song.” This femur is as much a way to make rhythm as it is a tool; but it is also an effective weapon. The primitive smashes on the downbeat. Next, the primitive throws the bone-tool-weapon up over his head, and as we see it spinning in the air, Kubrick makes a jump cut to weightless galactic travel. Out there, force is different. Or is it? As the viewer moves from earth to space, the bone is symbolically transformed into a nuclear weapons satellite.

The juxtaposition of temporalities made by Kubrick’s jump cut – the very old and the futuristic – is sutured by the merging of the two war-tool images. Back to the down beat – the drumstick, the club, and the nuke – are all common instruments. This strange synchronization is inseparable from the existential question of the human being per se, its origins, and its unchecked biological dominance. The femur’s drumbeat in 2001 is an auditory rendering of the repetition/cancellation paradox behind wanting to be qualitatively “Great Again.” This is true for both right-wing politicians in the US and many academics on the opposite political side. Categorical coherence is up for grabs because objects are quantitatively greater than they appear. To get the full weight of this challenge – its gravity, you could say – you must give up on the notion that there was ever a species so pristine as the human being per se. This is Crusoe’s drift again, another Odyssey.

With apologies for yet another image excursus, your question about the post- in posthuman war points me in the same direction as before: classifications like whiteness, and like the human being per se, are mediated in relation to other classifications; and between classifications, as time always reminds us, there is but an arbitrary (but far from impotent) demarcation of difference. Categories are mediated in relation to each other. They are best theorized as processes, interpretations, procedures, protocols, systems – whatever – but above all not static declarations of form or classification. Moreover, categories also do the work of mediation. They do mediation in different ways at different points in time (think of Jameson and Ralph Cohen on genre), which is technically, not merely consciously, determined.

This is an even farther-reaching point. But before going any further with it, let me just say that the prefix “post-” in posthuman war was meant to be in part a theoretical provocation. I also used it for the purposes of historical allusion. This is why there is so much history in the book – the English Levelers, native American genocide, the American War of Independence, not to mention World Wars I and II, Vietnam, and so on. The temporal issue you’ve seized on regarding my posting about the human being opens directly to the close association between weapons and tools.

If we can agree that the human being was never simply human and that the post- in posthuman war makes provocative redundancy rather than a moment of absolute difference, we should revisit some other key premises in On Posthuman War: Tools change, and when they do, so do the ways human beings categorize themselves, relate to each other, and know and experience the empirical world changes too. The book is theoretical in part but also has a lot of fact-based empirical researched. I really did do a hellish stretch with the USMC on the same obstacle course as Kubrick’s Private Pyle in Full Metal Jacket, shooting guns and breathing noxious gases. The documents I researched and the histories I consulted and wrote are archivally present and verifiable. This doesn’t make me a positivist or naïve empiricist – since we all know the archive is infinite – but I hope it does make me a good user of tools.

To extend the point about tools politically – as is implicit in your question – On Posthuman War tries to get at how femurs and hairy fists become ones and zeros. Anthropological appendages have been enhanced by tools for tens of thousands of years. There are historical lessons about how techne and bios overlap and co-evolve – creatively and destructively – that go back further in time than I’m able to go, which, as I said, was as far as the eighteenth century (the time of compasses, print, gunpowder, and so on). Computation is significant in war not because tools are new to human beings but because ones and zeros afford an unparalleled opportunity to explore a more recently quarantined zone of human and non-human intimacy, the one between human beings and machines (i.e. tools).

Maybe this is where the term you mention – Sympoiesis – comes in. I know about this from reading people like Dempster and Haraway. The concept of co-creation, as in symbiotic environmental interactions – corals and the like – is a theme in ecological theory. It provides an apt way to think about systems rather than identities and is totally compatible with my holy trinity: category, scale, and time. Sympoiesis also accords with the emphasis on “doing” over “being.”

My theory of ontology is sympoietic, rather than autopoetic, as should be very clear. But while war is all over the place in my favorite eco-theorists, I’ve only found one reference to it in Haraway. It’s in Staying With the Trouble, where trouble is described as “generative joy, terror, and collective thinking.” Haraway affirms our “many armed allies.” But with the “army” reference, I wonder if she was being metaphorical or literal. I must confess, I experienced a lot of joy-terror and collective thinking during my time with the USMC. It was utterly seductive. But this may not be what Haraway had in mind.

Trevor Paglen works great with what I was after by focusing on computation, though I didn’t have a good sense of his work until after I finished the manuscript. I’m embarrassed to say I have not read Mellamphy on larval warfare. It sounds totally intriguing. I would be curious to see how the issue of media, tools, or computation fits in.

With apologies to Kant, computation has placed the category of the human being into the “realm of means,” and there’s no going back. I wonder if this gets us into larval kinds of connections, as you’re maybe suggesting. I suspect it does. We’re all becoming larval anyway – in the literal sense of how our bodies decay. My favorite scene in Vandermeer’s novel, Annihilation, is where a pile of scholarly notebooks decay and become microbial, moldy, and organic. Similarly, you’re not going to wish (or police) AI way, and I don’t want to. Computation is useful and powerful. And – always and – it will be destructive. Maybe larva works this way too? In any case, whether this expansion of the “realm of means” means dancing with skeletons in Kant’s ironic sense or finding perpetual peace is anyone’s best guess. I think the two options are inseparable.

By this I mean not only that there is a dialectical relation between war and peace, with a strong war determination in the US at least, but also that the conditions under which war and peace are negotiated are determined by new media forms. Our media revolution – just like the earlier one based on print – introduces radically different ways of understanding time and space, and with that, redraws modern divisions between self and other, human and non-human beings, and of course, friend and foe.

So now, on to war. I like the term from Derek Gregory and still use it a lot. It’s the “everywhere war.” Maybe that would’ve been the better title for On Posthuman War, and we could’ve done away with the post! In any case, I take Gregory’s term because it refers to a very high-stakes change from earlier war concepts, the Westphalian or Clausewitzian state-based model for war, to a different one where the state-citizen connection comes apart. In the older model, the civilian is protected from political violence, and the soldier, who is taken out of civil society, is both allowed to wield and must be subjected to violence. This doesn’t apply in posthuman war.

Of course, there was always more than a simple friend-foe division within the older model or war, if you think about it more than superficially. There is the division between the state and the citizen, which, in return for the citizen’s willing compliance with the law, the state says it won’t ever cross. This is the basis of the social contract in Rousseau and of private property law in Locke (which included slaves, we must add); and then there is a second division, which recapitulates the first at a national rather than domestic level. That second line is the friend-foe distinction, which only the state can create. The friend-foe distinction writ large is what Clausewitz means when he says war is a duel at a larger scale. But this presupposes a stable civil society-type situation at home.

My first point in On Posthuman War was that the Clausewitzian dual no longer applies. This paradigm is jettisoned as a matter of official US policy after 9/11. As I detail in the book, The United States National Security Strategy (NSS) immediately following that event was partly a throwback to the era of the US War in Vietnam. In the NSS, counterinsurgency is the name of the game. Shadow agents are everywhere. Non-state actors move in-and-out of civilian populations imperceptibly, and in ways sometimes they don’t even know. Domestically present forms of terrorist insurgency are the primary concern. Remember the phrase, “if you see something, say something.” The all-encompassing vagaries of this canny phrase point to something profoundly important about netcentric war: It’s all-expansive. Even the repetition of the word “something” conjures up a certain paradoxical realization: There is no such thing as the neutrality of a thing; and even this statement is not neutral. What a desperate and pathetic-sounding slogan. Even the poor angel of history wouldn’t have said it.

As I quoted from one of the security training documents, The Terrorist Handbook, “terrorists are human beings.” This flipping back-and-forth between citizen and quasi-combatant has accelerated in US politics. The word “terrorist” is used by the federal government today with wild abandonment –everybody from student op-ed writers to peaceful environmental protesters are referred to as terrorists today. And this is a legal issue, not just a matter of the usual rhetorical bloat. Maybe the friend-foe flip-flop explains why federal law enforcement in the US now dresses up like bandits. Face coverings conceal their identity, and they seldom wear uniforms, ride in marked cars, or show badges. But face coverings reveal a lot, and in posthuman war, who needs identity anyway? You could say that there’s nothing under those masks but a series of more masks – citizen, combatant, police, soldier, friend or foe – they all switch around circumstantially. The hiding means there’s no more hiding!

As was clear according to US security strategy documents after 9/11, any adversarial political activity can be rendered into a terrorist one. But the rendering is the more interesting issue, and by rendering, I simply mean to refer to media – tools but also weapons. How all those “somethings” in the see-something-say-something mantra come out of so many “nothings” is a far-reaching technical question.

The technology isn’t highlighted at first in the so-called “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA), right after 9/11. But as I remark upon further in the book, an early catchphrase of the RMA was “bullets, beans, and data.” It was portentous. Weapons, food, and information are put on equal footing here, or better information is about to become a war tool in ways that are more significant than before. The weapons-information pairing marks not simply a departure from earlier modes of military mobilization. The emphasis on data as war matériel reveals how previous modes of war intelligence are absorbed into new ones, not simply left behind. To think about information as a martial art we must also admit that there is a critical merger between non-dualistic war theory and the prevailing form of technological innovation: both are network-centric. So, yes, drones, algorithmically coordinated camera surveillance, bio-metrics, the invention of the “soldier-sensor,” the “de-civilianization” of civil society, and so on. These were my specific examples of netcentric. They are both technical and deeply political examples of posthuman war. They are ontological examples only to the extent that ontology is displaced by operational systems.

Computation enables war strategists to think about civil society and the human being as very much within the “area of [military] operation.” And I don’t just mean the human being in the juridical sense of an abstract theoretical entity imbued with rights, protected from violence, obedient to the law, recruited into war but as soldier-not-citizen, and so on. I mean a turn from the legal abstraction of the citizen-subject to the corporeal mapping of the human being such that the body. In this kind of war, the human being per se a generic extension of the battlefield. This is why I moved in the book from demography, to anthropology, and to neuroscience.

The issue of technology is essential to my revision of the Clausewitzian duel: not On War, as his book is titled, but On Posthuman War – for better or worse! By agreeing to this title, I wanted to switch up Clausewitz beyond the way Foucault did when he embraced a definition of “politics as war by other means.” Remember, Foucault reverses Clausewitz’s phrase “war as politics by other means” by transposing “war” and “politics.” He’s trying to get at the fact that the secret inroads war makes into civil society – he called it “the fascism of everyday life” – leads to this weird combination of refusal-admission. We refuse to think we have much to do with political violence as citizens, but we admit we must pump up the war-machine to remain detached. We are a population, civilians, ourselves as much as a group of selves, who count in all the normal ways: enter biopolitcs.

But my interest in computation in On Posthuman War was meant to introduce something missing in Foucault’s reversal of Clausewitz, since he does not emphasize the way techne and bios converge. What he provides is the missing history of how they divide, how population is instrumentalized as natural or normative, how humanity becomes non-artificial. I wanted to focus less on war or politics in the Clausewitzian or anti-Clausewitzean sense and more on the third term in the triad, other means. I wanted to focus on the weaponization of media not simply as the evil twin of peaceful public activities but as a symptom of the public sphere changing into something else altogether.

DIFF: Building on your claim that it is essential to engage the computational foundations of ecological war — where, as you put it, “number rules”— could you elaborate on how certain philosophical trajectories, such as Correlationism, help foreground the ontological and political implications of number and computation?

In On Posthuman War, you notably draw on Alain Badiou, who warns that the proliferation of number “enfeebles every politics of the thinkable,” reducing politics to a numerically impoverished notion of the majority. Alongside Alain Badiou, you reference Quentin Meillassoux, Vladimir Lenin, William James, and Henri Bergson — a constellation of thinkers each grappling in different ways with the relation between number, mind, matter, and mediation.

Could you reflect on how their work has shaped your approach, particularly in framing number not just as an instrument of control or abstraction, but also as a site of struggle and potential transformation?

MH: Yes, number rules. This was the subtitle for an early section of the book, and it was in reference to “rule number one” of the post-9/11 training manual I mentioned, The Terrorist Recognition Handbook. I meant it literally, though it applies in two ways. First, it was fortuitous that the Handbook had rules for terrorist recognition, and I wanted to draw attention to what the rules were. But second, I realized the rules of terrorist recognition made better sense if you applied numeracy as a concept, which is what lists are. The numbers concept is this: because terrorists are everywhere – remember the first rule, they’re “human beings,” which covers us all – they are hard to find. See something? Say something? But paradoxically, something could be anything. If you apply rule number one, terrorists exist everywhere, and they could be everyone at any time. There’s simply no non-terrorist viewpoint from which to recognize the terrorist. Moreover, because other human beings are trying to apply rule number one, even trying hard to recognize the terrorist, you may also turn out to be one. This is where it gets interesting politically. It’s where the rubber of numeracy meets the road of political violence.

Let’s go back to Clausewitz. I said already his notion of military dualism no longer applies. I also said, to the extent it applied in the nineteenth century when he wrote On War, there were already real divisions within the divisions he wanted to maintain in his friend-foe theory of war: the inner division between state violence and the civilian is doubled by the division between friend and foe on the battlefield. But it’s still a stable paradigm. It’s a standard civil society model, running right through, as I said, from Westphalia to Hobbes and Locke, Kant, and more recently, Habermas.

But in the sense that number rules, none of Clausewitz’s divisions are maintainable. Rule number one says we among the citizenry are both friends and foes intermittently. And every act of externalizing the enemy is bound to fail, as the rule dictates. This is what I meant by saying posthuman war is autogenic – self-generating, even when trying to maintain peace. Rule number one unleashes what the US Department of State documents as the “functional combatant.” This means you don’t have to be “something” to have done “something.” You just have to be close enough to the information network to be put on the enemy list.

This is a spatial statement about posthuman war and how numbers rule. The network, as it is presented on screen, is of the foremost importance to how you fight war on terra firma. There’s a temporal dimension to how numbers rule in posthuman war too. As I said, rule number one means everyone might be a terrorist even if no one is, and the citizen in question does not have to choose whether to be a “functional combatant.” The automation of the enemies list is supposed to provide “kill chain compression.” The term comes from advancements in drone surveillance, where unmanned aircraft loiter over civilian populations to identify anomalies in movement patterns. These patterns are commonly seen both as physical movements and electronic data traces. There’s no difference in tactical terms. By mixing them you get a time advantage. The more you can “compress the kill chain,” the faster you are on the draw. “Before the enemy can reach for his weapon,” the pitch for this technology reads, “he’s already dead.” Seeing is killing, in this cinematic sense. The enemy is gone before he exists.

I used Badiou and Meillassoux (there’s no time for the others!) to help explain the virtualization of the battlespace in this way. But let me also elaborate on what I said about numeracy trumping political consciousness, since your question is about this explicitly. As I said, rule number one subverts the old idea that you are the enemy, and I am not. Schmitt is right on this. A stable friend-foe distinction is the lynchpin for maintaining civil society. It is the only way to preserve the ideal conditions for rational debate within the public sphere. But once you pull that lynchpin – your presumption of political innocence, let security against it, and your enemies – it’s game over. It’s game over not just for civil society but also for the civilian. As I have learned from experience, you’re suspect number one every time you leave and come back to the country.

The civilian is a juridical fossil – to use a Meillassoux word – a concept hollowed out in the name of its preservation. Once you start thinking about the citizen-subject as what the military calls “a force multiplier,” you’ve crossed the line that separates state power from the so-called ordinary life. This is where Badiou’s “numerosity of being” applies. Multiplicity itself – as in there being no more cardinal binary separating friend from foe – replaces that formerly peaceful and usually passive collectivity once known as population.

Cantor’s set theory is a helpful bridge from Badiou’s numeracy to Meillassoux’s rejection of correlationism. He also allows us to move smoothly between the “how” and “number” rules. Cantor says any set-group is only relevant to the degree it can be opposed to a set-group other than itself. So, you can’t know white without black; man without woman, subject without object, and, more to the point of our conversation, friend without foe. They’re simply bigger distinctions that activate a certain awareness about smaller ones. But as Cantor goes on to complicate things – and in revealing ways – the perception of likeliness between objects is habitual, not essential.

By now everyone knows that binaries are a bad way to organize reality, let alone make identity decisions or behave well in the world. Cantor offers a way to answer the question, what’s next? He says, while category A is dependent on category B, and while that dependency organizes – usually in sublimated ways – the elements within category A, there remain elements in category A that don’t match what they’re supposed to have in category B. Call these rogue elements, or less abstractly, the citizen released from her former state obligations. If some elements in a set don’t match their opposite set, then they don’t belong to either set. They belong elsewhere, that is, to other categories. Those other categories may already exist in some long-forgotten past, or they may have to be created. It’s why we have new genres and new disciplines replacing old ones – never easy and usually requiring conditions that are both joyful and terrible.

In any case, Cantor helps us explain why binary divisions between categories don’t last. He says this is because the elements within a given category are numerically superior to whatever set presumes to enclose them. The formulation is that the x-set versus y-set binary always also alludes to sets beyond just those two. Remember, the two contain many, and that’s where the real action is. Because categories have a plethora of attributes within them, they are never stable. For the same reason, the relationship between a thing and its category, while variously determinable and entirely conflictual, is arbitrary, not absolute.

The most useful way to connect this to correlationism is to think about the correlates not as individual entities – an individual, a thing – but as groups. I prefer groups for political reasons. Meillassoux doesn’t say so, but I see object-oriented ontology of his ilk moving on from what Althusser called subject = object adequation, only without Althusser’s interest (and mine) in class conflict. I’ve just added terrorist recognition to the subject/object relationship to politicize the friend-foe distinction along Althusserian lines. Terrorist recognition through object ontology means that nothing is recognizable as itself for long, yet everything is recognizable in some strange way. That strangeness is applicable to what I call de-civilianization – i.e. rule number one from the Handbook.

As is mentioned in his unpublished notes, Cantor relied a lot on Spinoza, whose notion of God/nature is founded in the same concept of the infinity of attributes in nature. It is a short conceptual step from saying after Cantor: (a) objects can never be adequated because they are internally divided; to (b) rejecting correlationism hides Badiou’s “essential numerosity of being.” This enters the political realm, say, of Hobbes, when you think his fear – based on the Levelers notion of property as a common treasury – of the multitudo overtaking civitas. Turns out Hobbes’ fear may have been well founded. Only in the posthuman war, property becomes common in even more politically violent ways.

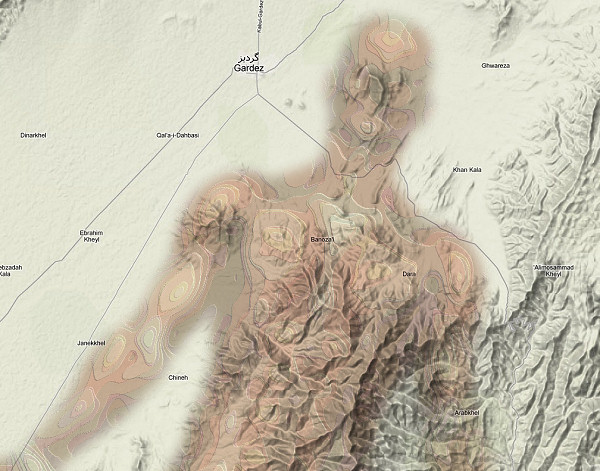

DIFF: Can you reflect on the anthropological undercurrents that inform On Posthuman War, and how your engagement with anthropological methods or paradigms has shaped your analysis? You write that “the terrain-ing of the human being goes still one step further: geology overtakes biology vis-à-vis a host of computational military tools”— a formulation that seems to displace the human from the center of war yet also reinscribes it as a site of strategic modeling.

Moreover, you examine the controversial U.S. military initiative known as the Human Terrain System (2007–2014), which embedded social scientists, particularly anthropologists within combat units to furnish cultural intelligence in Iraq and Afghanistan. As you lay out, this program was also met with severe criticism from the American Anthropological Association, accused of weaponizing ethnography and violating disciplinary ethics.

Beyond this example, can you elaborate on how such attempts to militarize cultural knowledge fit within the broader apparatus of posthuman war? Does war anthropology, even in its most compromised or instrumentalized forms, reveal something deeper about the epistemological operations of contemporary conflict, especially as the human becomes both datafied and deterritorialized across psychological, geological, and computational terrains?

MH: I appreciate that you picked up on that term “terrain-ing the human being” from the middle section of the book, called War Anthropology. It’s another way to think about the overlaying of the virtual and physical realities in posthuman war – or more accurately put, their tactical compatibility. It won’t win me any fans in the discipline to say so, but I was fascinated to discover how intertwined the history of anthropology is with war (as the human sciences in general are). Anthropology developed alongside the expansion of European empires and has always been linked to the violent appropriation of foreign territories. Although I studied the prehistory of anthropology in the book – it starts as you might’ve guessed, with Kant during the period of the Enlightenment – I found the use of anthropology in World particularly useful for setting up my approach to the US Army’s Human Terrain Systems program (HTS) in Afghanistan, which was deployed starting in 2007.

What you see in the US in World War II is an unprecedented amount of governmental funding headed towards the research of the anthropologists we all know – though their fame has cleansed them from association with military violence. I’m thinking of the work on national character studies produced about the enemy during the course of World War II, and how they were used by PSYOPS soldiers and other counterinsurgency fighters, for example, in British Malaysia.

In the 1940s, as an offshoot of war research, a concept of cultural rather than physical anthropology is set up as an absolute contrast to the biological determinism of Nazi ideology. Culture is given a moral imperative in that it’s said to be what makes us human: common humanity, not human-beings and sub-humans. On the one hand, the concept of culture dematerializes conflict and sets up human difference as a matter of shifting customs, ethical habits, group identity, social cohesion, “the psychic unity of mankind,” and so on. In short, these are the ideals of universal western humanism, and I don’t want to belittle them. But on the other hand, it’s a universality that depends on the material superiority of one state to destroy another and to force the vanquished to do the victor’s political will. Moreover, historically speaking, the universal category called the human being was a universalism of the relative few. That hasn’t changed. The victor’s political will in World War II is what got us all the borders erupting ever since: Korea, Central and East Asia, and Russia and Japan (the Kuril Islands), not to mention the Cold War, and alas, the posthuman wars of Iraq and Afghanistan.

While culture was clearly an “area of operation” in World War II anthropology, and as I said, federal funding for academic departments during this period is what gave the discipline academic standing, the national character studies scholars seemed to maintain that anthropology was nonetheless an objective science. During World War I, Franz Boas objected to President Wilson’s use of science as a cover for spying and sought to keep Anthopology safe from outside influences. In World War II, “culture at a distance” was Anthropology’s prevailing phrase, but that disappeared following the idea of participation-observation. The notion of distance assumes national character could be determined without the determiner being too directly involved. So, there wasn’t anything traceable to the mechanisms of power inherent to the work of anthropology itself, or there wasn’t supposed to be. You could do anthropology, and it could be adopted for war purposes, but there wasn’t supposed to be anything to suggest that anthropologists should be deployed in the field.

This changes as the concept of culture moves away from a scientistic understanding to an inter-cultural. The American Anthropological Association’s (AAA) opposition to using culture as a military tool started in the 1960s with an opposition to the US War in Vietnam. The US military’s counterinsurgency program during this time was not embraced by anthropologists in academic circles. And this extended vehemently to the AAA’s repudiation of the Human Terrain Systems (HTS) program in Afghanistan in 2007. But there is also a curious alignment between the AAA and HTS, that you wouldn’t have had in World War II anthropology.

In 1961, Robert Kennedy rejected a legal briefing citing the illegality of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. Here he flatly rejected preexisting neutrality laws. It was a harbinger of the “functional combatant” I mentioned in the post-9/11 context of the terrorist-as-human-being. As Kennedy insisted, there were no neutral positions.

As this plays out in the AAA’s condemnation of the HTS program, neither the producers of knowledge nor the progenitors of war wished any longer to think of human relationships – culture – outside the political realm. Regarding social organization, there is no neutrality; but neither is knowledge about social organization in any way neutral. This is a different position than that taken by World War II anthropologists in doing their national character analyses. And yet there is a second pivot, a technical one, which replaces the old notion of culture as a matter of psyches and values with numbers and so-called terrain. In the HTS program, it’s all data, which is coequal with bullets and beans.

Whereas classical counterinsurgency doctrine speaks of “the wind of revolution,” or of popular uprisings in terms of “the war of the flea,” the Human Terrain System’s version of the invisible enemy moves from a metaphoric explanation of network-centric violence to a virtual re-rendering of cultural relationships as a visual extension of the battlefield. Human and nonhuman entities entangle as informational entities in this virtual sense. In posthuman war, the terrain-ing of the human being means geology overtakes culture, as machines overtake the human being per se.

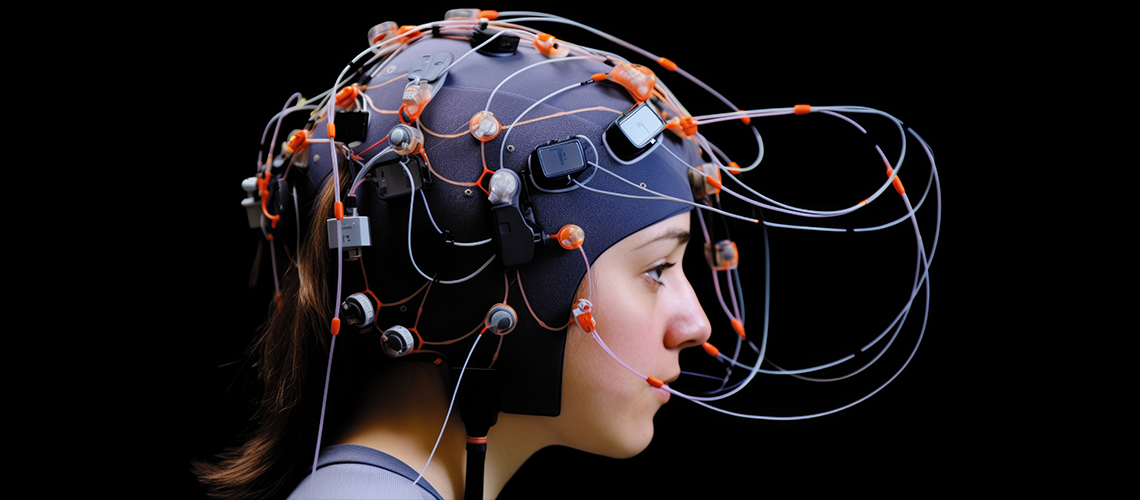

DIFFRACTIONS: Another critical strand you investigate is neuroscience, often positioned as the final or perhaps ultimate frontier of warfare. You provocatively assert that posthuman war is now a state of mind, pointing to the increasingly neurocognitive register in which conflict is being theorized and operationalized.

In this context, your book draws together the pairing of Henri Bergson and Norbert Wiener from Bergson’s vision of the brain as an image, a mediator in the temporal field of perception and action, to Wiener’s cybernetic engagement with white matter and nervous feedback systems. Could you lay out how their thought intersects with military science and how this lineage continues in contemporary neurotechnological programs?

In particular, how do you see their intellectual frameworks prefiguring or informing DARPA’s initiatives, such as those under the Biological Technologies Office—where research explores next-generation, electrode-embedded headcaps designed to apply high-definition transcranial stimulation, tagging memories during learning and reactivating them during sleep, in the service of enhancing warfighting capabilities?

Programs like these suggest a profound shift: the “skull-as-helmet”—a merger of human and nonhuman cognition, where brain activity becomes the terrain of optimization, intervention, and control. How do you interpret this militarized neuroscience in light of your wider claims about the emergence of posthuman war as a fusion of psychic, computational, and biological logics?

MH: I’d forgotten about the “skull-as-helmet” phrase. But it works for what I was trying to develop by moving from the terrain-ing of human relationships vis-à-vis the HTS program – permanent census taking in real time – to more recent military interest in the human brain as weapons system.

Military neuroscience is mind-blowingly fascinating, and reading Bergson only makes it more so: live insects flown by remote control; skull caps used to fly planes and fire weapons from great hemispheric distances; exoskeletons hardwired to the brains of super-soldiers; trauma memories erased and overwritten by nonexistent neutral experiences of past; and so on. It all sounds like science fiction. But for the war imagineers at places like DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), the fiction is what you start with, and the reality is what you get.

In the section of On Posthuman War on the HTS program, I talk about the importance of census taking – counting and categorizing populations of human beings to reliably distinguish civilian from combatant. As was the case in Vietnam, the US Army found that the friend-foe distinction was impossible to maintain in Afghanistan, and as I said, the line was deteriorating already within the so-called Homeland according to rule number one of the Handbook.

One of the peculiar things about census taking for counterinsurgency purposes is how color works. It’s not phenotypical, as with the US Census. In the US census, and as I also detail in the book, as of 2000 there has been an “all that applies” option. Since that time, you can identify in more than one category. Sounds to some like an extension of civil rights-minded reparative thinking: everyone has a right to identify themselves the way they think they fit in, right? But what Rudy Giuliani said while Mayor after 9/11 turns out to be more to the point about the unmaking of civil society in identity’s name: “You do not have the right not to be identified.” Given the rise of so-called multiracialism, the right, and the lack of the right, to be identified can create a state of demographic incoherence. This has dire consequences for enforcing civil rights.

My point about the demography section of the book was to point out a paradox around the issue of whiteness, at least insofar as whiteness might be effectively challenged by progressive civil rights-based jurisprudence. The paradox is this: The more kinds of categories individuals choose to identify with, the less possible it is to enforce civil rights law. The difference within the categories just gets too big and too complicated. If nobody adheres to the black/white binary, which is usually celebrated by critical philosophies of race as a negative thing, then you end up allowing for a civil rights-based prerogative to self-identify in a myriad of other ways.

The point of writing on the US Census in a book about war was to follow whiteness where it leads, to trace how it changes its normative shape as being co-equal with “American,” etc., and to become a point of connection between identity and political violence in a posthuman war kind of way. The US Army’s use of whiteness in the context of counterinsurgency census taking goes one step further than erasing the rights-based. As was screamed to me by the Drill Instructor on the first day of training with the USMC, “you no longer exist according to rights granted to you by the US government but are under my command according to the Code of Military Justice.” So, rights don’t exist here. In the same way, Human Terrain Systems gets rid of racial color coding altogether. Instead of racializing enemies, “white situational awareness teams” try to locate and map “white Afghans.”

In counterinsurgency missions such as Project Maven, “Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Teams” find friend-enemy patterns on the battlefield that are unrecognizable to mere human perception. But just like finding “functional combatants,” computational mapping renders these patterns knowable by processing information from many different points of view all at once. Off-site planning stations far removed from the battlefield channel demographic information in real time to the sites of forward command. At light speed, “Green Cells” map sewer lines, rivers, human insurgent movements, tribal loyalties, and the history of ethnic feuds, both flattening and expanding the concept of terrain. From “green data,” “white Afghans” are made.

As in rule number one of terrorist recognition, the whiteness of the white Afghan exists in a context where friend and foe are impossible to designate for certain and where battles are won and lost at the level of data ontology. If the numbers add up as green information, you can move friend and enemy forces in and out of the category of white. As the Afghan whiteness fails to become white or travels in and out of whiteness, green data should be able to follow the friend-enemy’s shifting shape.

I was shocked to find out how much whiteness lives on in the case of war neuroscience. It was almost too good (or too bad?) to be true! As in war demography and war anthropology, in the way military researchers operationalize the brain, the ever-present computer screen – virtual renditions of a more-real-than-what-you-see-as-real-reality – is everything. Images gain a reality-creating capacity. In war neuroscience and harking back to the Signal Corps of the 1860s, signaling systems have been central to military communication for a long time. You need good signals to place your fire accurately. But what about when the signal and the bullet are the same, as in kill chain compression?

There is an uncanny overlap between brain science and war discourse. The brain itself is regarded here as “signaletic material.” It’s not a metaphor. “Biocybernetics” remains one of DARPA’s most active programs. Its goal is to develop war-oriented neurotechnology that allows for seamless interface between brain functions and kinetic weapons systems. It’s not a stretch to say in DARPA speech that the brain is—at least functionally – just like a weapons system: a network compatible with netcentric renderings of the battlespace, a system of human cognition that can be grafted into the computational systems of war.

An example I like to use to make this point is the Department of Defense-funded program Targeted Neuroplasticity Training. The acronym – TNT – says it all! The TNT program uses algorithms to stimulate the soldier’s nervous system through the skin. This helps memory recall and other key war-making functions. Other programs mine the soldier’s brain for images the soldier may have seen but isn’t conscious off – the brain as a kind of alien war archivist. The point for me is not so much that the brain is being used as a tool to fight war in more directed or efficient ways – to compress the kill chain as they say – but that the brain is itself being understood as an extension of the battlespace. It is not simply how the warfighter’s brain reacts to explosions on the battlefield. Synaptic firings can be made concurrent with kinetic firing in the traditional military sense.

How can this be? I find Bergson’s theory of cognition as a process of “quantitative discreteness” useful to answer this question. His theory of mind foreshadows war neuroscience, conceiving the brain as a biophysical and mathematical organ, as well as a virtual-reality-generating machine. Sound familiar? For Bergson, the brain is first a computational maker of images, and only after this, a knower of things. I relied on William James’ reading of Bergson to get a better handle on this proposition, since the hard part for me was to understand how cognition could be both material (as in a chemical and electrical movement of matter) and immaterial (as in an image-oriented reality projector) at the same time. This is well-suited to the virtual aspects of posthuman war I mentioned with the HTS cultural mapping tools.

As James explains, Bergson refuses the idea that thought alone is adequate for understanding and experiencing reality. It reminds me of Marx’s aphorism about real-life not being determined by consciousness, but the other way around. Bergson’s anti-idealism foreshadows war neuroscience, in the first instance, by giving to matter a primacy over mere mental musings. Cognition is the result of material interactions with a reality exceeding (because it is the very stuff of) human ken. To the extent neurons fire and chemistry flows, cognition is a material interaction. This is what Bergson means by “image matter.” I added this: If it’s material, it can be quantified. And if it can be quantified, well…you know the rest from here: “bullets, beans and data.”

Weiner too is useful, especially his focus on what preoccupies brain scientists a lot these days: white matter. Wiener’s focus on white matter in the brain is appropriate for a computer scientist, which is of course where cybernetics comes from. (Cybernetics too began as a war discipline.) In the context of command, control, and communication – the three Cs of cybernetics – whiteness designates the myelin substance coating cells within the central nervous system. It’s meant to designate the cables from the sender, in telecommunication terms – white versus grey matter. White matter directs electronic flows in the brain to their neuronal targets and is essential for brain sectors to communicate with each other. But of course, white matter is also essential for communication between other human beings. It’s an information mediator, one that’s entirely compatible with other forms of war signal intelligence.

So, we’re now at a full circle, violating Kant’s sacred command. In posthuman war, the human exists not merely in the “realm of ends,” as Kant insists, but also in – or better, as – a form of “means.” In the myelinated sense, whiteness is the bio-chemical application of what’s happening in the applications of demography and anthropology in posthuman war. Now, not just culture is terrain-ed, so too is human thought.

6. As the geopolitical landscape is dizzyingly mutating through emerging conflicts, climate crises, neurotechnological acceleration, and increasingly autonomous system, do you foresee the conceptual terrain of Posthuman War evolving in any directions you have touched up? Broadly, do you anticipate your own theoretical framework shifting in response to new thresholds in warfare, cognition, or planetary-scale computation?

MH: Yes, the book I’m writing now is called Ecologies of War (unless the marketers change it!). It’s based on an article I wrote a long time ago by the same title and draws from one or two other pieces I’ve published recently on war and science fiction, on climate fiction, on “close reading at a distance.” and on the hypothesis that environmental warfare is going to be more important than the war human beings make between and within states.

There’s lots of good evidence for this, including changes in US national security strategy, which until the current Presidency – which in its willful ignorance of climate science is accelerating the ecologies of war –designates climate change as a force-multiplier. Since I’m interested in what comes after civil society, and since I feel like I’ve tried to answer that from a human perspective – or what’s left of it given technological change – the “what’s next” question ought to more expansively cover the political agency of non-human entities. We could say that, like whiteness, the weather is no longer just a banal part of so-called ordinary life, as in “how’s the weather?” The right response to that question, at least to me is: “It’s war.”

Computation has become incredibly sophisticated when it comes to climate change modeling. Very important states – like China, where nothing short of an electrotechnical revolution is afoot –their constitutions because of this new knowledge. You can drill down into ice and look at isotopes to study climate conditions from millions of years ago. Imagine what it must be like to go even half that distance forward. So, unlike in any of my books from before, I’m mixing computation with a more recent technology of imagination and virtual creation: printed novels. I’ll use computers to read them by putting a lot of text into data-based form to see what kind of patterns can be found by scaling up the amount of fiction I’d like to address. This is probably the only responsive way to talk about genre change these days, if the editors will have it, I’ll do some close readings too.

What a strange way to end our conversation, which has been all about the post- in posthuman war. But there it is!

REFERENCES

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Hill, M. (2004). After whiteness: Unmaking an American majority. NYU Press.

Hill, M., & Montag, W. (2014). The other Adam Smith. Stanford University Press.

Hill, M. (2022). On posthuman war: Computation and military violence. University of Minnesota Press.