This is the third part of a 3-part series The Left Hand of All Creation: How To Repurpose Whole Worlds by Michael Uhall.

In this regard, to repurpose an object of whatever sort entails an experiment or a gambit insofar as doing so is an attempt to test what an object can do beyond its apparent function, limitations, or purpose (i.e., its current prospectus) as inscribed in its descriptive apparatus. Consequently, to repurpose an object means two things: (1) we transform its prospectus into another prospectus and (2) we thereby change its place within the ontological networks that produce and sustain it. Repurposing always requires the intervention of speculative reason – that is to say, of positing a different world than the world we think is given.

On the one hand, repurposing is always a function of symbolic translocation (i.e., redescription), which refers to practices of reinscribing or shifting our symbolic formations (e.g., arguments, concepts, injunctions, metaphors, phrases, texts, words, etc.) into jarring or novel contexts. (In at least one sense, we already do this whenever we coin a neologism, fashion an idiolect, mix a metaphor, or even commit a malapropism.)

On the other hand, repurposing always effects a functional or material shift in the object as such. Either there’s a shift in what it does, or there’s a shift in what it can do. We err terribly when we think possibilities are irrelevant or unreal, because every object (and every subject, for that matter) is traversing a distribution of possibilities from instant to instant. That something is possible does not make it actual, but its possibility is a necessary precondition for its actualization. Hence, mapping and remapping distributions of possibility is the work of speculative reason. Because thinking is not a ghostly operation that supervenes upon the world without touching it, speculation remains a form of efficacious action – or, rather, it always and irreducibly accompanies what we identify as action in every case.

Accordingly, here’s a speculative attempt at an informal algorithm for repurposing objects (and therefore object worlds).

Step 1: Identify the target object.

Step 2: Explicate the descriptive apparatus attending the target object. (Note: Look especially for sticking points in the descriptive apparatus, which block or impede further negotiations and revisions.)

Step 3: Craft a redescription.

Step 4: Project possible effects of your revision of the descriptive apparatus (i.e., try to determine how the redescription affects the object’s prospectus).

In a preliminary fashion, let’s look at four example objects subjected to repurposing on this model: two technical artifacts (the Phillips screwdriver and earthships), a social construction (the family form), and a temporal category (the future). Hopefully, selecting such disparate objects will indicate something of the wide range of applications of this algorithm and, thereby, its usefulness as a means for conceptual salvage and (re)engineering.

Example 1: The screwdriver

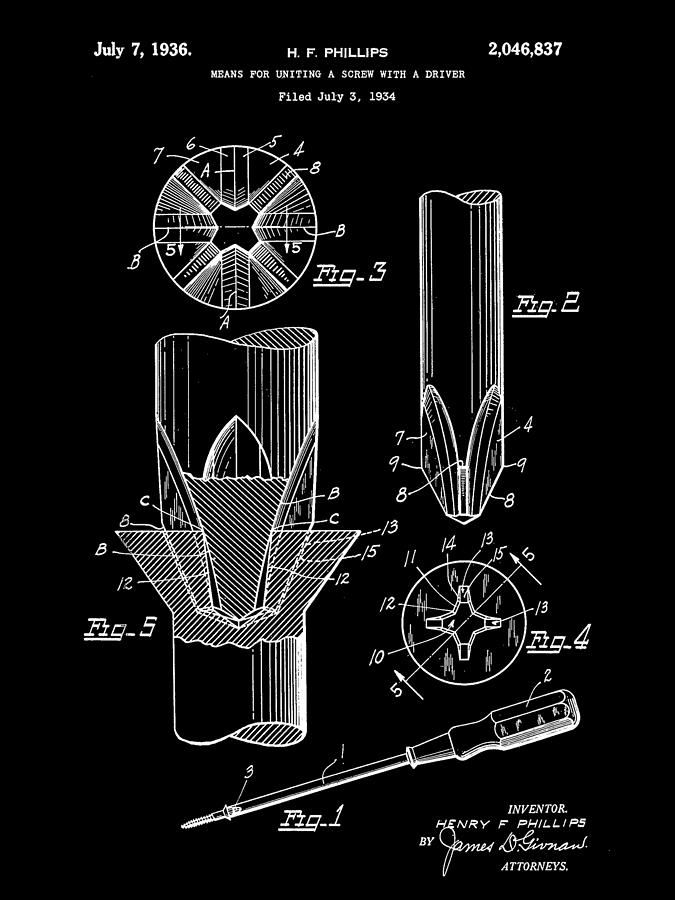

The Phillips head screw drive is a type of cruciform screw drive invented in 1932 (by John Thompson and later sold to Henry Phillips). Phillips head screws have a specific shape, namely, a cross-tip recessed socket, and Phillips head screwdrivers have tips engineered to fit that socket. In contrast to simpler slotted screws (which have a single slot socket suitable for flathead screwdrivers), Phillips head screws have several distinct advantages. Specifically, the Phillips head forces more precise alignments, because the screw and the tip need to be aligned properly in order to reduce angular offset (and, therefore, consequent irregularities in fit), and Phillips head screw drives also reduce the cam out potential (camming out refers to the tendency of the screwdriver tip to exit the screw socket after exceeding a certain amount of torque). In short, the physical form of the Phillips head screw and the Phillips head screwdriver imply each other. They also developed in tandem. They emerge from the same historical timeline of industrial invention and from the same processes of machine-tooling. Attending this abstract object – the Phillips head screw drive, of which any set of matching screws and screwdrivers is an instance or token – is a vast machinic ecology of practices and standards, as well as path-dependent sequences of accidents, decisions, other inventions, and various technical innovations. The Phillips head screw drive doesn’t have a mysterious additional property called its end or purpose, which magically accompanies it, but it does have a specific causal-industrial history that encodes its function heavily into it.

So take a Phillips head screwdriver as our target object. To explicate its descriptive apparatus, we don’t need to understand its history in great deal, but we do need to have a phenomenologically legible sense of what this artifact is – and what it’s good for. That’s part of what it means to live in a culture that knows what a Phillips head screwdriver is. If you can identify one, and you can articulate in use or words what it’s for (i.e., tightening and loosening Phillips head screws), then you’ve already identified it as a target object (Step 1) and (Step 2) explicated its descriptive apparatus (well enough to use it, anyway). Now say you’re not trying to tighten or loosen screws. Instead, you’re trying to pry up a bit of wood. It might well be that prying up a bit of wood would benefit from a prybar, but, if you decide to use a Phillips head screwdriver for prying, it may well suffice. But this necessitates Step 3. In order to use it for this other purpose, you have to craft a redescription of the Phillips head screwdriver, however inarticulately or informally. Here you can see how Steps 3 and 4 often coproduce each other. You want to pry a bit of wood, so you craft a functional redescription of the Phillips head screwdriver by applying it to a problem in a novel fashion. Now it is an artifact whose use has been expanded – that is to say, the object we call a Phillips head screwdriver, which encodes the Phillips head screw drive in the physicalist details of its material composition, is freed up for use and then used.

This is a simple yet paradigmatic case of repurposing in my sense: what an object is changes when its prospectus changes, and the change of prospectus may attend or follow from an alteration in its descriptive apparatus. Redescription is an active maneuver. We navigate object worlds and we negotiate with objects, in no small part, by redescribing them. Note that this does not imply that calling an object by a different name makes it so (names are only a very small part of the descriptive apparatus). Nor does it suggest that a redescription is guaranteed to be successful just because it is a redescription. To the contrary, failures in repurposing are common. A Phillips head screwdriver might work as a prying device, but it isn’t going to be a very good pillow.

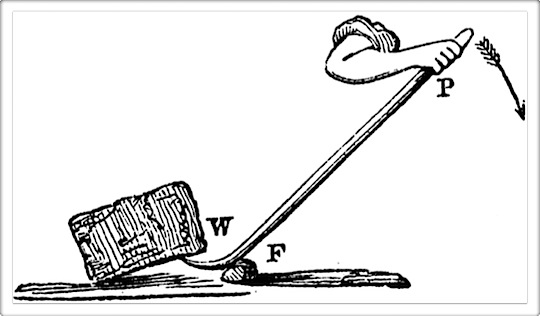

The principle of leverage.

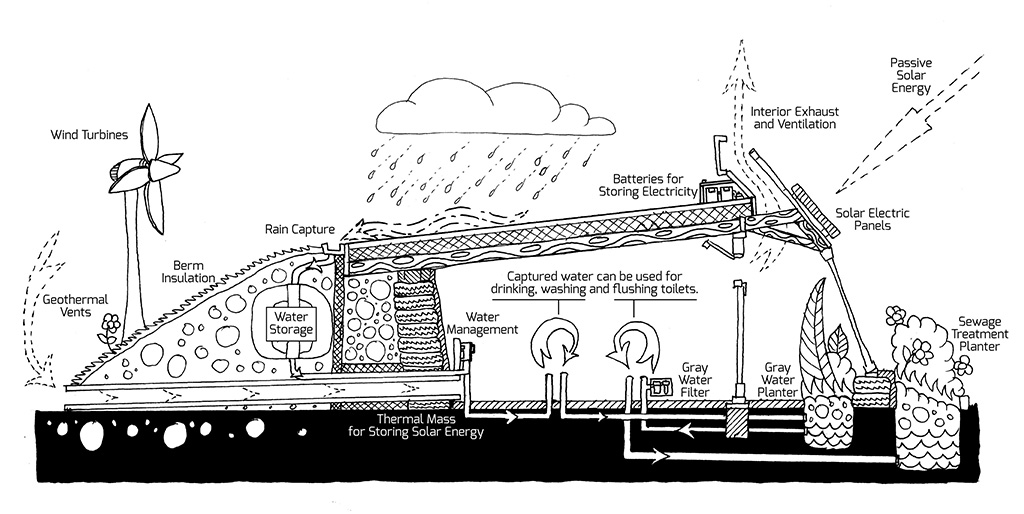

Example 2: Earthships: Paradigmatic “house” design: “a machine for living in.”

Let’s look briefly at a second technical artifact: the earthship. An earthship is a type of passive solar structure built out of various materials. Their inventor, the architect Mike Reynolds, has a pretty expansive vision of what earthships can do, or what they’re good for, but let’s look at just one dimension of the earthship object. First, there are the facts of their material composition. Consider an earthship largely constructed from soil and upcycled bottles. The old bottles are postconsumer waste products, initially produced in order to function as cheap and easily portable drink containers. After consumption, many of them are lying around as garbage. We can identify used bottles, and we know what bottles are typically for. Knowing what they’re typically for, we can start to play around with redescribing them. Filling the bottles with compacted soil, they become useful as construction materials. They can be repurposed. Redescribing them as construction materials enables the building of earthships, and this redescription, in turn, enables a redescription or repurposing of those objects we call buildings or houses. Hence the expansiveness of Reynolds’ vision (make of this what you will).

In any case, this illustrates how redescriptions tend to have multiscalar ripple effects throughout the object world. By contrast, the Phillips head screwdriver example I discuss above is artificially isolated in the extreme – on purpose, as if we didn’t already know that a screwdriver has lots of possible uses. Nevertheless, my point has little to do with epistemology, or what we already know or think we know. In the simplest sense, we know what a screwdriver is for, and we have to suspend what we know in order to repurpose one effectively. But I’m not really interested at the moment in whether or not we’re familiar with a given descriptive apparatus. Instead, my concern is with how repurposing works and, ultimately, how to effectuate or stimulate the repurposing of objects in the broadest possible sense.

Identify a target object: the nuclear family form, which is still commonly assumed to be among the most given or natural forms of human association. It’s irrelevant that, empirically, families often disintegrate or fail, or else serve as vectors of dysfunction. On the standard assumption, we’ve decided almost unconsciously that blood is always thicker than water. Even many critics of the nuclear family form hold this assumption, and seriously challenging or criticizing it tends to provoke a variety of defensive responses. These range from anecdotal counterassertions (e.g., “well, my family’s not like that”) to scientific misappropriations (e.g., invocations of some assumed genetic imperative) to kneejerk social conservatisms (e.g., claims to the effect that the traditional nuclear family is the core or essential or indispensable unit of civil society).

However, it’s worth noting that there’s something fundamentally accidental and necessarily nonconsensual about the nuclear family form. For example, it’s impossible to consult a child prior to her arrival, so family formation involves random assignment. Therefore, the nuclear family form can be in nowise elective. So how might we redescribe the family form (say, in structural terms), so as to enable or propitiate its repurposing and use? As I’ve argued elsewhere, withdrawing our emotional and social attachments from the nuclear family form as the primordial unit of human association frees up the ability to construct elective affinity groups that can do more – that is to say, that can accommodate more types of affective bonds, service opportunities, and social ties than can the nuclear family form. Our attachment to the nuclear family form undermines our ability to invest in novel associations that cohere firmly or reliably.

In contrast to the nuclear family form, and its implicit reliance on accidental associations and nonconsensual obligations, consider alternative and repurposed family forms that operate on the basis of bespoke relational options and voluntary obligations. In fact, even suggesting this (and it’s worth noting that, in reality, people already tinker with the family form all the time – although doing so with a consciously or vocally experimental attitude is still generally disincentivized and frowned upon, if not actively discouraged or punished) already constitutes a pretty strong redescription of the family form. If we find it difficult to imagine such an alternative (i.e., denuclearized) family form surviving, then perhaps this is because our culture rabidly perpetuates the narrative that all forms of elective affinity ultimately fail, whereas only the nuclear family form endures, despite its flaws (ironically, especially insofar as it gets ratified in terms of property holdings and their sequestration and transmission).

Let’s try it with the future. On one view, the future is a temporal category characterized by its not yet having arrived. On this view, there are three temporal categories or tenses: the past, the present, and the future. Time’s arrow moves forward in a linear fashion, such that the present turns into the future as it proceeds forward and what had been the present becomes the past. As such, the futures we imagine both sponsor, and derive from, our comportment and conduct in the present.

By contrast, consider the projection of a future that will retroactively determine its own past – that is to say, the very present from which we project futures (the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has it this way: “What is realized in my history is not the past definite of what was, since it is no more, or even the present perfect of what has been in what I am, but the future anterior of what I shall have been for what I am in the process of becoming”). This is a fancy way of saying that we can view the present not as mere openness or submission to a plenitude of amorphous futures, but, instead, as the necessary prelude to some specific future. “What is to be done?” becomes “What did we do?” and anxiety about the future becomes retroactive necessity. Consider this in more formal argumentative terms. At time t0 there is a specific state of affairs X that is open to a range of possible transformations of X from X1 to Xn. At time tn, X has transformed into some specific state of affairs X’ (being any X value between X1 and Xn). Between t0 and tn, X has changed – but, critically, it’s changed retroactively. At t0, X is the state of affairs that supported a range of possible transformations (from X1 to Xn). At tn, X is the state of affairs that precedes X’. It is only possibly but not patently this X’ at t0. In other words, the future does not have to be pre-scripted, either in terms of its content or its form. In this regard, I suggest that we need to destroy this object called the future: we need to learn to think like an apocalypse. As the apocalyptic imaginary takes shape for us, we foresee Anthropocene futures afflicted by catastrophe, devastation, and failure. However, the future as such – the real object – will survive its apocalypse. As James Berger notes of the apocalyptic imagination more generally:

“[…] nearly every apocalyptic text presents the same paradox. The end is never the end. The apocalyptic text announces and describes the end of the world, but then the text does not end, nor does the world represented in the text, and neither does the world itself. In nearly every apocalyptic presentation, something remains after the end. In the New Testament Revelation, the new heaven and earth and the New Jerusalem descend. In modern science fiction accounts, a world as urban dystopia or desert wasteland survives. […] Something is left over, and that world after the world, the post-apocalypse, is usually the true object of the apocalyptic writer’s concern.”

Through the work of the apocalyptic imagination, then, the future as an object can become freed up for its use in the present. My claim here is that using the future as an object makes possible political forms of life that can potentially address, recuperate, and survive the trials and tribulations of the present. This is a way of saying that it’s as if the apocalypse has already occurred – not because all is lost for us, but because our catastrophes and revelations alike make manifest the underlying logics driving us into disaster.

:: (PART 5): POSTFACE ON CHIRALITY ::

Günther Anders’ philosophy of technology (as developed most fully in his two-volume monograph Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen [The Obsolescence of the Human] [1956, 1980]) has yet to be translated in full, but it’s nevertheless a productive exercise to read its title against Anders’ own intentions – that is to say, the obsolescence of the human as a possibility or a promise rather than as something to be forestalled or mourned. In part, this is because we’re already quite familiar with his argument, so it serves as a useful foil. For Anders neatly encapsulates many current anxieties about the status of the human faced with the inhumanist dynamics of modern technics. In this regard, Anders is a prime representative of the very influential German critique of technology (see also Martin Heidegger, Arnold Gehlen, and Hans Jonas).

Throughout his work, Anders makes three central claims: (1) the technical artifacts we make can now outstrip us functionally – that is to say, they can do what we can do, only “harder better faster”; (2) the technical artifacts we make are made faster than we can (collectively or individually) accommodate, comprehend, model, or take responsibility for them; and (3) we find ourselves compelled by the imperative to make or do whatever we are able to make or do, regardless of consequences and considerations. Ultimately, this leads Anders to lament what he intimates is a new human condition, characterized by what he calls “Promethean shame,” or the experience of shame at the fact that we (humans) are born and not made (i.e., machined or produced in the manner of technical artifacts). For Anders, this new condition is inane and self-destructive. Even worse, it proceeds on the basis of a fundamentally erroneous apprehension of what it actually means to be human. On Anders’ view, to be human is to have your conditions given to you (by the accident of birth) rather than to make or remake them (as the so-called Prometheans desire or envy).

Against Anders, consider the icy black inhumanist rationalism of Ray Brassier, articulated rather cuttingly in his “Prometheanism and Its Critics” (2014). Brassier argues that critical or negative portraits of “Prometheus” (for a quite orthogonal reading of this figure, see Bernard Stiegler’s vertiginous reconstruction: 1, 2, 3) rely upon hidden and undesirable assumptions. For Brassier, philosophers like Anders (and Heidegger and Hannah Arendt and all the other philosophers of finitude) “presuppose that there is a neutral, which is to say, transcendently ordained equilibrium” inherent to the world at an ontological level. In other words, the following idea is simply assumed by such philosophers (and then weaponized, insofar as it is used to shut down inquiries and revisionary programs): that humans, in fact, have their conditions given to them (by Being, or existence, or God, or nature, or whatever, or whoever), such that introducing disequilibria (i.e., modifications or strong redescriptions) is arrogance and foolishness incarnate. For them, the very idea of repurposing ourselves, much less the world, is dangerous, indefensible, inhuman.

Brassier writes:

“But the world was not made: it is simply there, uncreated, without reason or purpose. And it is precisely this realization that invites us not to simply accept the world as we find it. Prometheanism is the attempt to participate in the creation of the world without having to defer to a divine blueprint. It follows from the realization that the disequilibrium we introduce into the world through our desire to know is no more or no less objectionable than the disequilibrium that is already there in the world.”

Principally at issue between Anders and Brassier is whether or not and to what extent our negotiations with objects (and, consequently, our navigation of object worlds) cashes out into a program of prescribed nonintervention or else warrants the program of strong redescription and repurposing I propose. This leads us to ask: Can we be pragmatists about everything – about ourselves, about whole worlds? In part, I’d like to suggest that we’ve already been issuing forth the kinds of revisions that critics like Anders lament. This isn’t because of some specific historical or technological turning point. Nor is it because humans are radically or uniquely “open” or underprogrammed in the way that quasi-existentialists like Heidegger and Arendt (or even poststructuralist figures like Jacques Derrida) sometimes suggest. To the contrary, it’s only insofar as we’re able to access or exercise rationality (and rationality is something you do, not something you have) that, as Paul Feyerabend famously claims, “Anything goes.”

But this is the fundamental insight underlying the operation of reason itself, because reason is a contingent, error-tolerant, and interminable process according to which any prior belief or statement undergoes tests that machinically produce its own revision. If reason matters, then we don’t have to commit to some immaterial voluntarism, but we also don’t have to cite whichever mythologies of givenness in order to secure our tools and workspace. In other words, “to understand the commitment to humanity and to make such a commitment, it is imperative to assume a constructive and revisionary stance with regard to the human.”

Call my stance a form of wild pragmatism. The purpose of a wild pragmatism isn’t to propose tentative solutions that we consequently reject or shelve when they fail to immediately transform the world. Instead, its purpose is to serve as a speculative engine that can’t stop generating affects, concepts, hypotheses, programs, questions, and regimes of description and redescription, all intended to emphasize and reprogram the exigencies at hand. This is precisely why, from the start, the sinister pathway of the object figures so prominently in my account. It avoids parsing the world out into passive objects on the one hand and active subjects on the other. Taking the object seriously in this fashion helps to avoid getting stranded in the desert of ontological exceptionalism (any ontology that starts off by asserting that “The human being is absolutely and constitutively different than everything else in the universe” is desertic). But note that meaningful ontological distinctions are nevertheless preserved, indeed, vivified – that is to say, distinctions between different objects and kinds of objects and object worlds. The flat ontology I describe doesn’t eliminate verticality. Mountains and valleys are part of the landscape, not radical breaks from it.

Practically speaking, perhaps the most important distinction of all is the distinction between the sinister pathway of the object and the workspace of the subject. Workspace here refers to the domain of possible activity (constrained in all sorts of ways, yes, but open to expansion and revision) that each subject occupies. Think of the workspace almost as a peculiar type of prospectus attending the peculiar type of object we (for now) call a subject. Objects pass through the workspace all the time, and it’s in the workspace that object use takes place. This opens up a new model for conceptualizing object use. Instead of mere dexterity, for which passive objects get manipulated by a more or less dexterous subject (what Winnicott calls object relation), the workspace model allows for the agency and autonomy of the object as a precondition for its use. It even leverages that agency and autonomy in order to make repurposing the object more feasible and flexible.

In closing, consider chirality: the property that describes non-superimposable mirror images. In mathematics, chiral knots refer to knots (i.e., to circles embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean spaces, or in 3-spheres, which are higher-dimensional analogues of spheres) that are not equivalent to their mirror images. A relatively simple real-world example of a chiral knot is the trefoil.

Chirality also informs biological and chemical structures (like the bilateral animal morphology, or enantiomers, which are chemically identical molecules that nevertheless evidence chiral differences in atomic placement, leading to surprisingly varied interaction effects), as well as gene expression. Another way of thinking about chirality is that it is the constitutively structural asymmetry inherent to the handedness of the world. Handedness – this is not to imply that the world was made by hand, much less that it was made for human hands. Chirality, or handedness, is a way of characterizing productive asymmetries. Think of chirality as a conceptual scheme or a toolset that can be leveraged; the only way to follow a sinister pathway is by crabwalking in thought. Coordinate the right hand with the left in order to repurpose the world. Recall an old dictum from the early days of structuralist anthropology: “The right hand stands for me, the left for not-me, others.” Or, as an old book says, sheep on the right, goats on the left.

GLOSSARY

agency: The capacity to produce effects (in the most general sense).

activity: The production of effects (in the most general sense).

autonomy: Irreducibility (which does not imply inexplicability).

causal strangeways: See “On Causal Strangeways.”

chirality: The property that describes non-superimposable mirror images; handedness.

descriptive apparatus: A semiotic complex; the contingent and historical penumbra of signs that attends or contributes to an object.

dexterity: Exogenous direction or manipulation of objects.

object: An intersection, or a nexus, of various ontological strands. Note: Think of an object like a knot consisting of various strands complicated or entangled in a certain way. An object world is a set of differentiable objects that “hang together.”

object use: Coordination with objects or object worlds in order to produce intended or patterned effects. Navigation of object worlds; negotiation with objects.

progeny: The objects or object worlds that occur in the wake of other objects or object worlds. Note: Crucial here is (1) the temporal order (progeny come after; they succeed their predecessors) and (2) a nondeterministic processual linkage (progeny uptake elements or resources from their predecessors in novel ways).

prospectus: The apparent function, limitations, or purpose of an object; the range of what an object can do.

redescription: Altering the descriptive apparatus in order to change the prospectus of an object; a preliminary step to repurposing an object.

repurposing: Altering what an object is by changing what it does; may require preliminary steps of redescription.

sinister pathway: The inherent, specific tendencies of objects; their agency and autonomy.

standard assumption: A background assumption (or set of assumptions) that exists relatively commonly, which both constrains and purports to legitimate the descriptive apparatus to which it belongs. For example: “objects do not act; only subjects act” or “the future will resemble the past.”

workspace: The domain of possible activity each subject occupies.