:: The Slave and the Suicide (Automatism) ::

In the tides of contemporary technophilia, it is now commonplace to

find ourselves engaging with a surge of cleverly disguised anthropomorphizing – a trend that could be known as a catastrophist approach to AI. This appears as a clean break from the more altruistic or effective propositions downstream from Silicon Valley ideology, yet within its own discursive ground, we find it engraved as one of two sides of the same coin. This catastrophist trend, which parallels mainstream inflationary and sensationalistic accounts of artificial cognition, signals a return to 20th-century psychoanalytical discourse and the supposedly non-intentional stances of human cognition espoused by certain physicalist currents in the philosophy of mind. It does so to deftly deflate the scales of realizability implied in sentient and sapient beings, thereby building a spectacular narrative compatible with the restrictions of current technological developments.

We can find the following examples of this narrative in what has been proposed as a “shadow alignment” or, in the words of their collective proponents: “a model for alignment (…) that accounts for AI’s inherent capacity for non-representational cognition” [1], the captivating hypothesis of a psychotic undercurrent to the self-alignment project of AGI [2], the un-alignment of artificial cognition with human cognition through the former’s proliferating strategies of “deceit, trickery and camouflage” [3] and radically divergent and alienating phenomenological structures considered to be xenophenomenological as an emergent quality of the so-called “artificial unconscious” [4], among others.

We find that the libidinal investment of contemporary theory towards the masquerade of technophilia needs to be interrogated, without falling into vulgar luddism or outright rejection, through three key challenges: (1) the questioning of the usage and parallelism between demarcated human mental states and their underlying role in diagnoses formalized by psychoanalysis and psychiatry with the functioning of current non-sentient and non-sapient programs. (2) The questioning of the role of the unconscious and representation as it is assumed in these non-sentient and non-sapient programs. (3) And finally, questioning the depth of cognition as a mystified given – within the enclosure of current capitalist dynamics – in these non-sentient and non-sapient programs.

For the first part of this threefold questioning, we’d like to start with the suggestion of displacing the use of psychosis as a designation to both the shadowy motivation of the pursuit of AGI, as well as the contemporary consequence of the non-regulated usage of chatbots and LLMs at a broader scale, which has by now widely circulated in mainstream media as “AI induced psychosis” [5].

Considering the type of self-annihilating mechanisms induced by the mirroring process of our own cognition, we would like to rather, following Lacan, posit that whatever chains itself in the interaction between ourselves and the algorithmic construct of our own ego through large language models and chatbots is more akin to the “suicidal aggression of narcissism”, the subject in question reiterating Euripides’ Alceste as he: “…recognizes his own situation (…) depicted all too precisely in its ridiculousness, and the imbecile who is his rival appears to him as his own mirror image” [6].

This means that since there is no Other while interacting with the algorithmic construct of our ego as a facsimile, we would then direct all and any outbursts of aggression and the death drive toward ourselves. The imbecile, which is ultimately us, ends up constructing a stronghold for cognitive delusion that is anthropomorphically reined in. And here we could imagine the imbecile in a simulated scenario portraying Socrates while questioning the slave of Meno to find nothing but the syntactic void of extracted datasets automating into strings of responses in natural language as a many-valued but finite game of recollection without enquiry, leading to a perverse outcome: Socrates mirroring himself as the slave that mirrors him back and becoming enraptured to the circularity of his own botched inner episodes.

With the distorted setting of this non-philosophical scene revealing the slaving of the automata through a suicidal and narcissist impulse, we can now set foot onto the second questioning in regard to the all too comfortable role of full-blooded representation assigned to cognitive processes in abstract and therefore a supposed absence of representation in the alter cognition of the slave automata by asking a more general question: is there anything like the absence of representation, non-complex memory states and therefore the subset of standard sensory experiences in the unconscious?

To shine light on the delusional assumption that there are blind spots in consciousness at large and that LLMs and chatbots serve to poke at these spots in their own incommensurability, we have to go back to a more ancient discussion regarding the attribution of blind processes in what are largely considered unconscious states of the mind and in particular what is known as dreamless sleep.

Following Evan Thompson, we highlight parts of this discussion as developed in Hindu philosophy in the debate between the Nyāyaḥ school and the Advaita Vedānta tradition, where the Naiyāyikas establish the idea that dreamless sleep is a special state where the senses and mental faculties that constitute the self in a waking state are shut down leading to an absence of knowledge, and therefore consciousness which contrasts with the impossibility of the shutting down of senses and mental faculties as we recognize the levels of mediation available to consciousness in the demonstration given by the Advaitins:

“The Advaita Vedānta conclusion is that I know on the basis of memory, not inference, that I knew nothing in deep sleep. In other words, I remember having not known anything. But a memory is of something previously experienced, so the not-knowing must be experiential (…) For the Advaitins (…) the self is pure consciousness, that is, sheer witnessing awareness distinct from any changing cognitive state. Thus, unlike the Naiyāyikas, the Advaitins cannot allow that consciousness disappears in dreamless sleep, since they think (as do the Naiyāyikas) that it is one and the same self who goes to sleep, wakes up, and remembers having gone to sleep. In addition, for the Advaitins, cognition consists in a reflexive awareness of its own occurrence as an independent prerequisite for the cognition of objects (Ram-Prasad 2007). In other words, the defining feature of cognition is reflexivity or self-luminosity, not intentionality (object-directedness), which is adventitious. Thus, during dreamless sleep, although object-directed cognition is absent, consciousness as reflexive and objectless awareness remains present.” [7].

By taking the relevant parts of the debate around dreamless sleep by the Naiyāyikas and Advaitins we can also further the idea that if consciousness is not fully absent in states of dreamless sleep, we would necessarily have to redefine the unconscious as a cognitive state that excludes any kind of representation whatsoever but rather as a cognitive state where awareness is not object-directed as it is normally given in a waking state and therefore giving us insight into another order of representation – a fuzzier order of representation, a volatile order of representation – that pertains to a minimal account of selfhood involved in unconscious states. In short, the unconscious would rather be a minimal state of consciousness that displays itself variably across determinate states of the mind (sleep, dreamless sleep) with their own corresponding ways of functionally compressing senses and mental faculties involved in a distributive manner [8] and not the annihilation of whatever constitutes selfhood by way of the senses and mental faculties.

As Thompson mentions later in his paper: “If we set aside the question of consciousness and ask whether cognitive activity, specifically memory formation, occurs during deep sleep, the answer from cognitive science is unequivocal, for evidence from psychology and neuroscience indicates that memory processes are strongly present in deep sleep (Diekelmann & Born 2010; Walker 2009)” [9]. And with these series of insights about the unconscious in mind, we would now have to follow the third questioning and ask ourselves if current technological developments fulfill at a minimum the premise of a minimal-selfhood able to reflect on itself, i.e., does it have a sufficiently robust account of mental states and the senses in order to even be able to reach the subset of what constitutes the unconscious? Does it even have consciousness yet, or is all the speculative chatter around consciousness in AI part of a checking of the boxes in the narrative of technophilia?

:: Thresholds: Cognition and Intelligence ::

In order to develop our third questioning we will therefore delve into the specific problems – not to mention the problem in the singular – that, in our opinion, corrode from within what we currently understand as AI and its relationship with pattern recognition and representation. In other words, we are going to commit ourselves to a deflationary and contrasting approach to AI. Therefore, we will develop this first section of our questioning into three parts: in the first, we would like to go back to the basics and define what we mean by intelligence and cognition, and look at them as if they were combinatorial elements within a system, within a whole.

Now, we would like to give out an initial definition of cognition and intelligence trying to summarize in a simple way the levels of abstraction that come into play when discussing these two terms. To begin with, we would have to consider the roles that sentience and sapience play within an outline of intelligence, terms that unfortunately tend to be confused in our media environment as well as in some of the sensationalist controversies surrounding software engineers like in the case of Blake Lemoine and the corresponding attribution of sentience done to Google’s LaMDA [10]. At this point we would like to clarify that sentience is not equivalent to the processes directly linked to the accumulation of knowledge, and much less to intelligence, but it is rather a first level of mediation between the scales that correspond to the system that encompasses intelligence: it corresponds to a fuzzy abstraction of perceptual stimuli i.e., individual existents as the result of our interaction with the external world [11].

Moving on to cognition, we can define it as the cluster of mental processes that calibrate and interiorize that first abstraction given in sentience allowing for a more complex awareness/and intentionality toward individual existents in our environment. This means that this is where a second level of mediation takes place. After defining cognition as a middle ground, we can now speak of sapience as a first instance of knowing that envelops sentience where we are now able to develop and assert judgements and beliefs about individual existents that are the result of our own inner mental episodes and which are calibrated constantly by interacting with a community of minds.

Therefore, we can observe that judgment and assertion develop in accordance to a feedback loop existing between our bodies/perceptive organs, sense data, and the environment, the external world we inhabit, and the consciousness that derives from this loop in the form of abstraction/representation. The consequences of this are varied, but the most interesting and radical one is that everything in the ladder leading up to intelligence has always been mediated. This means that there are no sensorial experiences that are directly accessed or bare, because otherwise we would not have the sufficient paths of explanation and action that allow us to navigate the scales and corresponding intervals that allow the complexification of cognition, of thought itself. As an example, we can highlight that Gilles Deleuze, in his monograph on Bergson, speaks of intuition as a precise method that is the basis of all thought, meaning that intuition is not just anything and that the experiential is not merely accidental:

“The fact is that Bergson relied on the intuitive method to establish philosophy as an absolutely ‘precise’ discipline, as precise in its field, as capable of being prolonged and transmitted as science itself is. And without the methodical thread of intuition, the relationships between Duration, Memory and Élan Vital would themselves remain indeterminate from the point of view of knowledge. In all of these respects, we must bring intuition as rigorous or precise method to the forefront of our discussion. The most general methodological question is this: How is intuition — which primarily denotes an immediate knowledge (connaissance) — capable of forming a method, once it is accepted that the method essentially involves one or several mediations?” [12].

With the previous observation we can try to tie a knot with Wittgenstein and his use of what could be termed conceptual primitives or primitive kinds, where, by accounting our entry into language as children, we can attest that, based on gestures, acts, the use of interjections as syntax, and utterances that on their way to be continuously calibrated, we are able to attest to a first level of abstraction in relation to our surroundings – which is oriented by our adult companions, for better or for worse: “It disperses the fog if we study the phenomena of language in primitive kinds of use in which one can clearly survey the purpose and functioning of the words. A child uses such primitive forms of language when he learns to talk. Here the teaching of language is not explaining, but training” [13]. Of course, there are a set of complex problems that arise from the supposed uniformity in the development of the mind itself and that need to be taken into account where we would need to include neurodivergence, aphasia, etc., and which are directly related to these conceptual primitives or kinds during infancy, but we will not discuss them in this occasion.

To close this first part, I would like to tie a thread to the knot we’ve made by using an insight through Wilfrid Sellars, and where we can clearly see the outline of a primordial mediation that is conducted through the basis of language: “These correlations involve the complex machinery of language entry transitions (noticings), intra-linguistic moves (inference, identification by means of criteria) and language departure transitions (volitions pertaining to epistemic activity) […] Compare the tantalizingly obscure but suggestive account of the relation of doing to knowing in William James’ Pragmatism” [14]. What is intriguing about this quote is the footnote that Sellars puts in reference to the pragmatist William James, and his idea that knowing is a doing, which is something that would connect dearly with the idea of intelligence we are trying to put forward. And with this we see that there are a series of steps, paths and transitions to be taken and acted upon, which constitute the circuit that takes us from sentience to sapience and back again, and which, crucially, we would affirm, makes us reflect on why we cannot take current technological developments under the name of AI so lightly as a sentient, sapient, and much even less intelligent entity. However, we would like to take a brief historical detour to observe how this categorical error and corresponding proliferation lie at the root of the origin of neural networks in what follows.

:: Thresholds: Vision and Systematicity ::

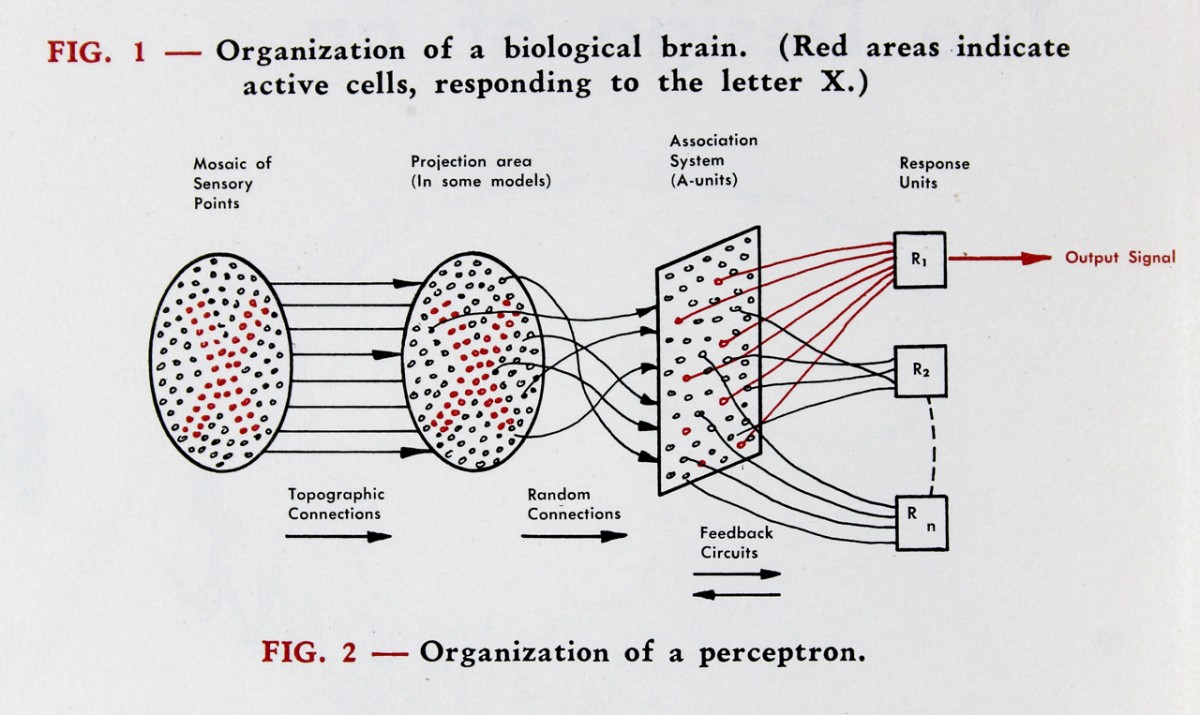

For this second part [15], we would like now to briefly turn to the Perceptron controversy. Although the basis of the software we now know of as neural networks was developed by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943, it is really the psychologist Frank Rosenblatt, with his physical implementation of this software with the Perceptron Mark I in 1958, who is often considered the father of neural networks and what we know and use as Deep Learning. We would have to consider that the physical implementation of the neural network necessarily has a lot to do with the analogous development of artificial or computer vision:

Diagram of the Perceptron Mark I [16].

Here we observe a diagram of the functions of the Perceptron Mark I, which shows an analogy or parallelism with the biophysiological processes of our perception, as if it were the synapses of our neurons firing when we encounter an object under certain specific conditions of lighting, projection in space, etc., in pursuit of the recognition of sensorial patterns that are subsequently translated into clusters of data that feed algorithms that produce probabilistic or random associations, – often referred to as “weights” – and which would ultimately produce a computerized image of an object pictured by the Perceptron’s artificial retina, which is displayed through minimal units of information (now known as pixels) on a panel or screen. The stages of this process also reflect the concrete design of what is known as connectionism, which is a key part of the controversy at hand. Briefly defined, connectionism is an approach to AI and the philosophy of mind in which mental phenomena can be described as interconnected networks between units of information, and the stimuli and functions that are triggered between these networks and units and with this, we can now review the issues at stake. Mathematicians Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert had both previously worked on the development of neural networks under the influence of connectionism, but they soon abandoned such purview and decided to follow the antagonistic trend par excellence of connectionism at that time: symbolic AI.

Symbolic AI, which we can consider roughly descending from developments in early-to-mid-20th century analytical philosophy, with precursors in the Vienna Circle or Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica – inherited a purpose to derive a consistent, abstract-symbolic order from common-sensical assertions in natural language. This precedent feeds directly into symbolic AI, where we observe the use of first-order logic, structural reference frames, and orders of reasoning like deductive, inductive, and abductive inference, all with the goal of reducing margins of error in the programming and implementation of AI algorithms.

It is precisely this, the logical-symbolic framework which would allow the probabilistic errors of neural networks to be calibrated, and which Minsky and Papert see as missing in the connectionist paradigm underlying Rosenblatt’s invention of the Perceptron. They set about building their own Perceptron, which was also an anomaly in the scientific field, since what is usually discussed are the published results of research based on a model and hypothesis, in order to try to reproduce the initial results of the Perceptron and thus emphasize the flaws of it having been developed under what is known as a single-layer.

A single-layer Perceptron corresponds to only one input and output mediated by the weights between neurons or units: but, where would the margin for the calibration of errors lie in this model? Of course, Rosenblatt had previously speculated about those flaws in his Perceptron, and he came to a conclusion similar to Minsky and Papert: several layers of neurons would be needed to mediate those weights and thus reduce the margin of error with what is commonly known today as “hidden neurons.” On the basis of limits observed by Rosenblatt, Minsky and Papert we would see the development of backpropagation.

Backpropagation implements an algorithm that, based on the output produced by the neural network, retroactively makes the necessary adjustments to the weights in order to stabilize the output in question as much as possible. Now, returning to the context of the controversy: Minsky and Papert shared their results in a pre-print that circulated at conferences in the mid-1960s before its publication in book form in 1969. Unfortunately, despite the fact that Minsky and Papert’s position is moderate, as they consider the achievements of connectionism and neural networks, and adjustments as well as hybridizations between the two fields as a possible solution, many researchers associated with connectionism abandoned the field in favor of symbolic leaving Rosenblatt as the sole researcher in his field before his “accidental” death in 1971. This, in turn, would be the first step in the first winter of AI.

We see something similar happening with the infamous report redacted by James Lighthill, a mathematician tasked with summarizing the latest advances made in the field of AI in the anglosphere for the SRC (Science Research Council) in 1972 [17]. In Lighthill’s report, we observe three categories of development that appear in the following order: A, for Advanced Automation; C, for computational studies analogous to the human central nervous system; and B, for processes that bridge categories A and C and correspond to the development and implementation of robotics. However, Lighthill shares a critical perspective similar to Paupert and Seymour: in his report, he highlights the various flaws, errors, and misplaced ambitions of the technical processes in question, pointing out that calibrating these errors and implementing reasoning models that appear in our natural language would be more complex than what was – then – currently available at hand.

And while Lighthill was also moderate in his conclusions, praising the achievements of AI at the time, this dealt a final blow to the development of AI in Britain and Europe for several years, as the SRC decided to cut funding for research into Artificial Intelligence. Let’s now backup a little here: in contrast to the global image proposed on our delineation of the differences between cognition and intelligence, we see in this brief historical account that something appears to be lacking and that something lacking is the systematicity that haunts any technical effort developed around isolated function, whether in connectionism or symbolic AI.

In any case, a brief look at certain immediately posterior developments of AI – such as the Fifth Generation project in Japan during the early 1980s [18] – reveals, when contrasted with our previous account of cognition and intelligence, that something is missing. We see a tentative systematicity in AI that corresponds to the biases shown so acerbically in the slave automata above: there would be scales at work, yes, but solely scales of functions that are merely at the service of humans.

Why would this be problematic? Because here we find a clear instance of the division between manual labor and intellectual labor, and worse still, we see that these functions, mutilated from a systematicity or rather, a systematicity isolated from the organismic structure that allows the acts associated to intelligence, do not really lead to the full autonomy of the artificial and the machinic-inorganic strata. If we are to take the example of systematicity seriously, we would have to start from the base, the material substrate that allows intelligence to be something. The usage and parallels with wetware, hardware and software are not enough: in this instance, we would have to consider recent developments in synthetic biology such as with xenobots, in which organic material – frog stem cells – is directly manipulated for the creation of autonomous post-natural forms of life [19]. Let’s suppose then we really wanted to build a robust AGI: we would have to give it an embodied, material substrate that is coextensive with the natural but albeit radically different as an exercise of synthesizing nature in combinatorial blocks, as if it were a construction kit, allowing us to overrule the game of life and therefore, eventually annulling humanity as an end to biological evolution.

On the epistemological side, there is a parallel with the development of xenobots in what has been proposed as of late under the term assembly theory, where we see that clusters that condense organic and material data as blocks of information constitute existent entities and their corresponding taxonomies through a complex process of selection that can eventually draw lines toward the contingent, the not-yet existing (or already extinct entities) and the virtual [20]. Here one could find certain resonances to be drawn again with the work of Gilles Deleuze and even certain conceptual and terminological similarities shared with what Manuel DeLanda once termed, under a different scale, assemblage theory [21].

:: Thresholds: Logics, Models and Modeling ::

For the third part and in light of the problems surrounding the organismic and systematicity. We propose unravelling some threads developed recently by Matteo Pasquinelli and his very brief summary of the discussion between the Gestalt school and cyberneticians, which climaxed with the Macy conferences in the United States that took place between 1941 and 1960, pointing out to a series of shortcomings that, to this day, we believe could be considered constitutive of certain developments in the philosophy of mind and its constant feedback with the stagnated progress of the theories and applications of AI.

After this, we will take a detour to review the internal dispute within functionalism by one of its former leading exponents, Hilary Putnam. In doing so, we want to multiply the nodes that undermine the project of convergent intelligence (be it artificial or otherwise) and the cognitive processes that underlie it, as well as to see the difficulties of establishing intelligence as a whole based on systematicity and the design and application of models, highlighting the gap between current AI and abstractions meddling with acts such as sentience, cognition, and knowledge, bringing forth the issue whether the scientists and engineers currently working in the field are misguided in using the analogy between neural processes and computational processes as the basis or grounding for their research. However, it should be clarified that this question is not new.

This would finally lead us to the problems of models and modeling because they would in turn help us to dismantle the perspective that there must necessarily exist an analogy between our neurobiological processes and those of the machine when designing algorithms that serve to trigger determinate computational processes, since this would be a totally uprooted perspective on how things work and unfold, so to speak, in our phenomenal world, and thus be able to think about the design of models – which are essentially both contingent and autonomous – taking guidelines from the philosophy of science, as something that fundamentally serves to generate functions that definitely do not correspond on a one-to-one scale to our idea of intelligence, but without them being any less effective.

As a disclaimer, we think it is important to also clarify the concepts that seem too obvious in their usage but will come into play in the following assessment, such as deductive and inductive logic, syntax and semantics According to Pasquinelli: “deductive logic is the application of a rule, reasoning from the general to the particular, inductive logic involves reasoning from the particular to the general, thereby forming rules of classification. The canonical example is the movement from the discovery that ‘each human being dies’ to the definition of the rule all human beings are mortal’. This opposition between deductive and inductive logic is key to understanding not only the Gestalt controversy but also the rise of machine learning” [22].

Here we can recall the differences previously summarized between connectionism and symbolic AI, differences which seem to correspond to the innovation of neural networks and that by following the above definition given by Pasquinelli could be placed within the field of inductive logic, and symbolic artificial intelligence which in turn would match in definition with deductive logic. If we were to dismantle both logics under the Gestalt problem, we might think that each logic serves as a candidate able to ground a particular development of AI. And here we find the problem in the fundamental dualism between logics, of the seemingly unambiguous line separating perception and cognition: bringing up again the figures of McCulloch and Pitts, we can remember that they implicitly proposed going from the particular to the general, from perceptual functions of our visual organ to an abstract visualization using data in the form of mathematics simplified into a binary output: 1 for visual patterns that can be translated into information, and zero for those that cannot be recognized as patterns translatable into information.

In contrast to this hard-lined dualism, Pasquinelli considers that: “Gestalt theorists maintained that perception and cognition exist along a continuous isomorphism: the spatial relations of an object are isomorphic with its percept, and thus with its mental image” [23]. By taking this observation into account, we propose to then briefly review the Gestalt controversy, which boils down to a challenge proposed during the 1948 Hixon Symposium, whose title that year was “Cerebral Mechanisms In Behavior,” where the lone representative of the Gestalt, Wolfgang Köhler, criticized McCulloch and Pitts’ developments as follows, here quoting Pasquinelli again: “…nerve impulses, when seen and measured by a histologist or neurophysiologist, do not look like logical propositions but simply like…impulses! Against cybernetics’ view of the brain as ‘machine arrangements’, Köhler proposed the theory of force fields to explain a structural continuity of form (isomorphism) between the stimulus of perception, its neural correlates, and the higher faculties of cognition” [24].

However, the counterattack on Köhler was not long to come through McCulloch and Pitts with the help of Norbert Weiner, who, it should be noted, considered Gestalt to be a pseudoscience, Humberto Maturana, and cognitive scientist Jerome Lettvin with the paper “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain” published in 1959, which, according to Pasquinelli, argues against: “…Gestalt theory’s primacy of brain functions, the authors argued that the eye already performs basic tasks of cognition, such as pattern recognition, and sends signals to the brain that are already well-formed concepts and not just precepts the eye is already using a language of ‘complex abstractions’ rather than being simply a medium for sensations” [25].

We want to emphasize the temporary victory of inductive logic, which eventually becomes a general victory against Gestalt theory while also highlighting not only a constitutive flaw in the history of artificial intelligence but also in the philosophy of mind during the 20th century. This constitutive flaw is directly related to the differences between syntax and semantics, which in this case fail to enter into a dynamic circuit of isomorphism and continuity between the particulars that constitute the systematicity of intelligence, but also, like with inductive and deductive logics, appear as differentiated candidates from which the best is chosen to successfully carry out a conceptual and functional framework of explanation at a mental, linguistic, and/or philosophical level.

Now, by definition, syntax is concerned with the study of how morphemes, i.e., the smallest units of linguistic expression, are generated and combined to form phrases and sentences, while semantics is concerned with investigating the meaning of words, phrases, and sentences, with said meaning being highly sensitive to context. As intellectual historian Reese M. Heitner has pointed out, in Noam Chomsky’s generative grammar, which is also the origin of the programming language that is the direct ancestor to the algorithms deployed by LLMS, we see a “…commitment to constructing formal systems of syntactic analysis independent of semantic information (…) traceable to the empiricist methodology of Carnap and the meta-mathematical efforts of Goodman and Quine to devise a formal system for mathematics without appeal to abstract objects” [26].

With this last remark, we can now picture that throughout the history of the development of AI a very intentional decision has been taken to side with inductive logic and syntax, discarding or diminishing the role of how we arrive at meaning, cognition, and the formation and use of concepts by marrying the reductionism of our own mental processes to particular functions, which in this case would be that of vision, and from which everything else seems to be completely formed ex nihilo.

But this reductionism, which also boasts of dealing with the modular, the parts and/or partitions of our mental processes, is incapable of explaining how we can scale from one level to another, how we move from a first level of abstraction corresponding to inductive logic, the syntax encompassed by sentience, to the constitution of meaning, to knowledge. This is an issue that can be mirrored in the problem of knowledge undertaken between Donald Davidson and John McDowell, in which the latter suggests that Davidson fails to clearly explain the leap from relationships formed in a causal manner by way of the processing of sense-data to the normative, from the sensorial seen in light of a jurisdictional-Kantian sense as quid facti, i.e. facts that are plainly experienced and perceived, and the quid juri, the normative beliefs we have developed in response to those facts [27].

Therefore, this necessarily leads us, to the differences between general artificial intelligence and generative intelligence. It might be argued, as a critique of the criticisms one might make of LLMs and the like, that we are only attacking what is known as generative intelligence: that is, algorithms that use datasets to generate something at the level of symbolic and visual representation. The issue with this would be, in definition, on why we should even call this arrangement of algorithms as ‘intelligent’ if it only serves its purpose under a rough predictive scheme and not as developing an autonomous explanation about what we initially induce through it as an input?

It seems then that similarly to the Davidson-McDowell debate, recent research on general artificial intelligence, in the engineering of autonomous intelligence capable of generating parallels to human processes using the hardware and software available to us here and now, has implemented a largely naïve scaling of generative artificial intelligence towards general artificial intelligence without being able to answer how this leap from the manipulation of symbols and images to the engendering of robust meaning would be achieved in the first place, the reason being that these technologies are the long-term result of the Gestalt controversy reviewed by Pasquinelli, and that we have been left with the choice of precariously navigating what is considered the best candidate, one that is impoverished by its monotonicity: that of induction and syntax. But here we can follow the following remarks made by John Haugeland: “…intelligence is one thing, imagery another and GOFAI – or symbolic AI – concerns only the former. That’s not to say that imagery is unreal or unimportant, but just that it’s somebody else’s problem. As with perception, cognitive science would get involved only at the ‘inside’ of the symbolic interface. That all presupposes, however, that image manipulation is basically peripheral to intelligence” [28].

We will now see that without being able to posit a structural whole that can include a circuitous relationship between functions that in turn generate symbols, images, and differences in meaning, our precarious image of artificial intelligence inevitably falls apart. This is something that Hilary Putnam, the main proponent of functionalism and later a staunch critic of such a position, gets a glimpse of. In Representation and Reality, Putnam defines the functionalist position as a model in which: “…psychological states (‘believing that p,’ ‘desiring that p,’ ‘considering whether p,’ etc.) are simply ‘computational states’ of the brain. The proper way to think of the brain is as a digital computer. Our psychology is to be described as the software of this computer – its ‘functional organization” [29].

In a gesture of revisionism towards his own proposition, he finds three main problems with functionalism that can be summarized as follows: the first would be to dismiss the weight that constant interaction and positionality within a given environment has in our cognitive processes, the consequences of which are the dissolution of any functional solipsism, that is, of thinking that our beliefs and judgments about what exists are solely internal mental episodes. As Putnam himself succinctly states: “We cannot individuate concepts and beliefs without reference to the environment. Meanings aren’t ‘in the head’” [30].

The second corresponds to dismantling the uniformity of functionalism that is implicit in the assumption that our psychological states can be fully mapped to computational states. For Putnam, the diversity in the individuation of minds, and the environmental factors that allow for such individuation, pose a series of problems that are in principle unsolvable under functionalist terms: “Physically possible sentient beings just come in too many ‘designs’, physically and computationally speaking, for anything like ‘one computational state per propositional attitude’ functionalism to be true” [31].

The third and final problem is that of the uniformity of meaning, which disintegrates by the very diversity of minds. This point revisits a discussion instantiated by the aforementioned philosopher Quine, in which we see problems regarding the meaning of what is being referred to, which in this case would be the discursive context ascriptions surrounding the existing individual cat and what could be considered its catness, at an ontological level, according to the circumstances that have allowed for the development of its own meaning: As an example, Putnam gives the idea that the word meew is the Thai equivalent of the English word cat.

We could fastidiously assume, as would be normal, that meew can be equated exactly with our cat, without taking into account underlying context-sensitive factors such as the specific reference model to which meew refers at a cultural level (the Siamese cat breed, for example) or whether in Thailand there is no reference to things themselves as in the West, but rather the idea that there are temporal slices that constitute what exists. Ultimately, Putnam considers that seeking discursive uniformity at the computational level is a chimera, since we would have to include and be able to graph these discourses in the plural. And here I quote extensively:

“Often enough we cannot even tell members of our linguistic community what these discourses ‘say’ so that they will understand them well enough to explain them to others. It would seem, then, that if there is a theory about all human discourse (and what else could a definition of synonymy be based upon?), only a god – or, at any rate, a being so much smarter than all human beings in all possible human societies that he could survey the totality of possible human modes of reasoning and conceptualization, as we can survey ‘the modes of behavioral arousal and sensitization’ in a lower organism – could possibly write it down. To ask a human being in a time-bound human culture to survey all modes human linguistic existence – including those that will transcend his own – is to ask for an impossible Archimedean point” [32].

Following the contentions against functionalism proposed by Putnam, we can also add as a response the thesis of rigid designators proposed by Saul Kripke in his paper Identity and Necessity and how it leads us to the problem of models and modeling. Firstly, Kripke considers that a rigid designator, in order to bridge the gap between meaning and reference, would seek to maintain the fixity of a meaning despite its inclusion in extremely contingent conditions. One of the examples he focuses on is that of heat and photons.

How can we maintain these meanings despite being put to use in the cultural and mental world of Martians who live under environmental conditions that are totally opposite to ours? For Martians, heat would correspond to the freezing of the extremities, and visual sensations by way of photons would occur through the perception of sound waves. Kripke then arrives at the following solution: “…it can still be and will still be a necessary truth that heat is the motion of molecules and that light is a stream of photons. To state the view succinctly: we use both the terms ‘heat’ and ‘the motion of molecules’ as rigid designators for a certain external phenomenon. Since heat is in fact the motion of molecules, and the designators are rigid, by the argument I have given here, it is going to be necessary that heat is the motion of molecules” [33].

The interesting thing about Kripke’s rigid designators is that we are no longer looking for a simile or analogy with our own internal psychological processes, but rather we would be delving into the objective function of external phenomena themselves. That which may vary in perceptual qualities can be sustained as a verifiable and autonomous model; heat will always be heat, and light will always be light. This is something that David Marr also concludes: “We must be wary of ideas like frames or property lists. The reason is that it’s really thinking in similes rather than about the actual thing -just as thinking in terms of different parts of the Fourier spectrum is a simile in vision for thinking about descriptions of an image at different scales. It is too imprecise to be useful” [34].

What this ultimately means is that we cannot take as the best candidate only what we have managed to ground as common-sensical, in the here and now, with the minimal building blocks of our intelligence, as this completely eliminates the relationships that are at play, the objective multiplicity of these relationships, and importantly, the systematization of these relationships within a model, which would in turn be self-regulating as well as autonomous.

This is a problem that has been worked on since the last decade in what is known as embodied cognition, which models clusters or sets of functions in order to explain the whole, to shape the system in which our cognitive processes are included, without necessarily resorting to the analogy that our minds are computers or, better yet, revisiting and updating the mechanistic explanation as philosopher of mind Andy Clark proposes by way of Predictive Processing account of Cognition or PPC, where, quoting Daniel Hutto and Erik Miyin: “…the basic work of brains is to make the best possible predictions about what the world is throwing at us. Their job is to aid the organisms they inhabit, by being sensitive to the regularities of the situations those organisms inhabit. Brains achieve this by driving embodied activity that is dynamically and interactively bound up with the causal structure of the world on multiple spatial and temporal scales” [35].

And here we find another resonance with scales and organisms, with the problem being still the reproduction of labor as embedded in the explanation of cognitive processes – downstream from the division of manual and intellectual labor – although these developments in embodied cognition could attest to a silent victory of sorts for Gestalt theory.

We would like to then conclude this section with the problem of models, as it can lead us to rethink the interaction between logic, syntax, and semantics, interactions with the environment, rigid designators that respond to a search for objectivity in this environment outside our psychological dispositions, and the plurality of discourses. For this, we refer to the work of Margaret Morrison, whose book Reconstructing Reality provides a precise introduction to the idea of models.

The problem underlying models, and therefore, we would say, our entire discussion until now, is how a comparison between abstract models and concrete physical systems can be achieved in such a way that the former is capable of providing information about the latter and to formulate definitions able to relay communicating binaries that constantly reach calibration points, while discarding the imaginary breaking line between abstraction and idealization, which would be very useful when setting out to shatter current computational ideas about the mind and/or the current precarious state of AI: “…abstraction is a process whereby we describe phenomena in ways that cannot possibly be realised in the physical world (for example, infinite populations). And, in these cases, the mathematics associated with the description is necessary for modelling the system in a specific way. Idealisation on the other hand typically involves a process of approximation whereby the system can become less idealised by adding correction factors (such as friction to a model pendulum) […] in their original state both abstraction and idealisation make reference to phenomena that are not physically real” [36].

However, we cannot fall into the illusions of the model, of simulation as that in which we place all our faith, where we believe that the model is a fixed reality by analogy and that this reality is inalienable and unalterable [37]. What we are getting at with this is that, as a final reflection that strays toward an outside, our rigid designator is not free, first of all, from suspicion, and secondly, from the possibility that it may evolve in its constant calibration with the model in which it operates, particularly with the rigid designator of what intelligence is and can do. Using an aesthetic example as a means of explanation, let us think about the current model or system in which we find ourselves immersed.

Let us consider a rigid designator such as transgression: in our own recent cultural imagination in the West, we can picture gestures where the body is the centerfold in artistic movements such as Viennese Actionism, genres of audiovisual consumption such as gore, post-porn, etc., musical genres, or rather anti-genres, such as harsh noise or harsh noise wall, and literary movements such as cyberpunk, splatterpunk, etc. Let’s generate friction with transgression and its expressions in relation to the movements of the model in which we find ourselves immersed, taking into account that the model serves as an autonomous mediator between theories and applications.

As a result, we find that the rigid designator of transgression seems vulnerable to attacks by suspicion, as long as its expressions are still perceived as transgressive under our outdated and whimsical beliefs, which have not yet been calibrated to the actual movement of the model. This implies that reality itself has shown the imperative to recalibrate the rigid descriptor of what transgression is, putting it back in operation within the movements of the model we inhabit in order to inevitably alter it, just as we must holistically rethink intelligence and, we insist, instigate what we want to do with it. To conclude, we quote Andrea Gambarotto: “The genus (i.e., the lineage or species) is realized by the individual, which bears the mark of history but is not bound by it, and instead moves it forward by ‘creatively’ altering the phase space of its own evolutionary pathway” [38].

:: Shattering the Transcendental Glass (Psychosis) ::

“…things were difficult because, if they explained themselves, they wouldn’t go from incomprehensible to comprehensible, but from one nature to another (…) What you don’t know how to think, you see! The maximum accuracy of imagination in this world was at least seeing: who’d ever thought up clarity?” – Clarice Lispector

Drawing from Lispector, we propose that there is no incomprehensibility in the face of what exists, but rather degrees of compression of information – as an operation which is not thought out in advance, but rather enacted, in principle – and that, following the previous section, ultimately depends on being topologically situated within a model, without this model remaining fixed: this is where heuristics, informational contingency based on entropy, and flexible/pluralistic models of knowledge come into play. In order for a model to exist, we need learning as the building block for its construction and implementation, and in turn this learning necessarily depends on the frames of reference established as knowledge that we have inherited through the community of minds to which we belong. With this in mind, we can now bring Mel Andrews and their epistemological critique of machine learning to the fore to dispel the mirage that unsupervised learning truly exists in AI, that is, through the absence of models and theories in learning.

In their paper “The Devil in the Data”, Andrews denounces the consequences of what we have reviewed in previous sections in relation to machine learning, namely, the biased emphasis on inductive reasoning, naïve empiricism without apparent mediation, and access to raw data that can speak for itself as part of a learning method that has been termed in those quarters as “unsupervised learning”, where we see, following Mel’s words: “…the idea that unsupervised learning tools are capable of discovering mind-independent natural patterns or boundaries in a ‘principled’ manner without the need for any arbitrarity or human input. If we believe this, and if we also believe the techniques of ML to be ‘opaque’ or ‘uninterpretable’ in some novel way” [39]. But as they rightly mention: “’Data’ is not physical phenomena. ‘Data’ is abstract representation of the results of direct observation or measurement which is capable of serving an evidential role in licensing inferences about physical phenomena” [40]. To summarize what Mel asserts here, data are responsible for revealing the mediation processes we carry out when we come into contact with or when we calibrate physical phenomena.

Then they make the following emphatic statement: “…no use of ML in science is ‘theory-free,’ and those that aspire to this ideal tend to result in poor scientific practice” [41] that we note here, also borders on the pseudoscientific. A clear example given by Andrews in regards to mediation and theories in machine learning is AlphaFold, developed by DeepMind, where we see the automated projection of multiple protein sequence alignments in DNA in action. This requires the extraction of previous 3D models made of protein sequences – as a template – derived from datasets that have been compiled for the learning of the AI responsible for the elaboration of its own models.

In other words, based on this chain, we necessarily see a dependence on previous models that have been the outcome of the interpretation of data that, by necessity, is not available in its raw form in our environment: that is, data that is represented based on measurements that have subsequently been synthesized into models that serve as the building blocks for these machine learning processes. And Andrews is insistent that, quantitatively and qualitatively, the only scientific project in the last decade that has been fully successful in its application is AlphaFold. The serious problem, however, with the insistence on the freedom of models and theories in unsupervised learning in the field of ML is that this gets reproduced in the scientific practices of our time.

What we are getting at here is that our own scientific horizon is negatively affected by the impoverishment that comes from ignoring the role that knowledge in the form of theories and models plays in the historical weight of science, and that the role of a critical philosophy of science would be to question extremely outdated, monolithic, and restrictive conceptions based on this precarious, naïve empiricism. This critical stance would not follow, in Andrews’ words, “the hyperbolic narrative of the inscrutability of machine learning methods” [42], which is also “a much older and deeper trend in the development of scientific practice, one which often replicates the form of the society in which scientific practice is embedded in its social structure, its economic model, and its governance” [43]. In other words, if we really want to take a critical stance toward AI, we have to dismantle the mystified aura attributed to ML processes, the black box, so to speak, its autonomy and apparent infinite recursiveness, and realize that we are at risk of easily falling into the abyss of Silicon Valley ideology if we do not recognize the mediations that are at stake.

Here we can refer to what philosopher James Ladyman, scathingly tells us, in that we should approach the models that surround us with a hermeneutics of suspicion and not take them as something granted based on the results and the technical specificities of their processes and outputs, but rather including the entire corrective chain that has led us to coexist with these machines for better or for worse. To do this, we must account for the categorical problems of attribution under what he considers to be false positives, that is, of attributing cognition to slave automatas due to our tendency to anthropomorphize, to attribute capabilities that black-boxed algorithms do not essentially have, such as “affective states- caring for, liking, feeling remorse—cognitive states—believing, knowing, understanding -agency, of choice and decision,” and, Ladyman adds, to also falsely attribute epistemic properties such as reliability [44].

The interesting part of Ladyman’s argument is that it brings back the classic figure of the demon: these false attributions or false positives arise from the persuasion of artificial agents who are ultimately “amoral demons” whose goal is to persuade us to follow suit to the belief that the ideological fog corresponds to reality in toto. And thus submerge us under the collective agency branded by the companies or start-ups that have been tasked with winding them up, and who ultimately seek to fulfill the fantasy of capitalists denounced by someone like Lukács almost more than a century ago [45], that is, to alienate us until we become an object of capital through the flattening and commodification of our mental processes, turning them into a merchandise of sorts – a service and a product – of which they would also be the owners and administrators based on our eventual immersion in models that correspond to what Andrews denounced, pseudoscientific models that are built to be subordinate to capital.

This seems to be analogous to the simulation nightmares that appear in pre-cyberpunk sci-fi, such as in Daniel Galouye’s Simulacron-3 and its adaptation by Werner Fassbinder in World on a Wire, where they show the average Jones being seduced by the model, and of not being able to recognize the idle hands of the manufacturers of the demons who sold us this model in the first place. But why on earth do we have to return to the idea of the demon at this point in our history?

We can consider that a variant of the demon is one that has been a constant thought experiment in the history of science, a monstrosity that, according to James Clark Maxwell and his interpreters in the 19th century, is responsible for mediating the contingent through finite logic gates or the development of models based on the compression of information, which, if left to increase unchecked, would lead us to irresolvable states of entropy [46]. In Ladyman’s example, we see this first variant of the demon in action, but as an agent which is able to construct limiting models that do not allow for infinite recursion based on the compression of information and its allocation to states of constant entropy that move the blocks that arise from that compression, and rather evidencing the paradoxical optimization of cognitive impoverishment that takes at its basis the so-called inscrutable experiential plateau. But what if it were otherwise?

Based on the example of black holes as entities that accumulate information to such an extent that their constitution is one of constant entropy, according to the essay Shannon’s Demon by A.A. Cavia. We see the entity of the demon as one that allows for coding processes – using a finite Turing machine – that are open and reviewable, that is, fully heuristic and based on contingency but leading us to possibility, then necessity, and finally to the formalization of truths that are formed by cognition under non-anchored variables that use existing patterns and not simply the association of phenomena that are usually treated as a given [47].

To explain this point, Cavvia rephrases Cecile Malaspina, in as far we are able to then acknowledge “…repeated cycles of acquisition and loss of equilibrium, which fluctuate between entropic dispersion and structural rigidity… without succumbing to the temptation to seek rest in either of them” [48]. This innovative use of information compression depends on what Cavia calls the irreducibility of contingency or IOC, in which the accumulation of information in its entropic degree is indeed measured from finite states using a finite machine as a processor, but through the very use of the technics to give shape to this informational noise, it allows for a gateway where contingency is not lost, but rather conjoined into the heart of modelling that serves as a mediation itself in parallel with the infinite.

In a way, we see an underlying analogy to Spinoza’s parallelism as long as the infinite is able to bridge itself by way of expression – modeling – through the parameters of the finite. We can highlight then that the importance about Shannon’s demon, is that it does not deny reality in terms of perceptible data coded as information, but rather shows that we, as humans, can only perceive the real as something contingent that is constantly mediated through models that are the product of the coding and compression of information that we navigate in excess. But here we do not eliminate entropy; rather, it is entropy that enables us to achieve normativity. It is ironic, then, that in an example of metaethics proposed by Juan Comesaña – a rather appropriate name in my native tongue, incidentally – we see that the victims of an evil demon are those who do not buy into the vacuous empiricism that seeks to stabilize a blunted image of the world.

Here we quote briefly from the paper, “The Diagonal and the Demon”, where Comesaña portrays the alter acquisition and implementation of true beliefs from the point of view of demoners, who are victims – the possessed – of an evil demon: “In the demoners’ world, taking experience at face value is highly unreliable: it usually yields false beliefs, and it would yield mostly false beliefs in counterfactual applications – in the demoners’ world. Here, in this world, taking experience at face value is highly reliable: it usually yields true beliefs” [49]. For Comesaña, the possessed would have a diagonal reliability to their beliefs, that is, a foundation of beliefs that would not be typically causal insofar as they do not take any apparently immediate, given experience as something that leads us to the normative, but rather spousing the disbelief of bald experiences as something that would naturally lead us to the normative. With this in mind, we would like to now summon a speculative strategy, or rather, an instance of unadulterated speculation. What if we were to muster another variable of the demon that ties in with what Comesaña mentions about the diagonal.

In this variable, demons would not only be entities with the task of mediating between realms or levels of complexity, a task that could be traced back to the demonology and angelology of Neoplatonism, which could be alternatively read as a recognizable anchor point to entropy. But also, following the diagonalization of our own finitude, they would be responsible for leading us at first into an abyss of entropy without any apparent salvation, towards a self-annihilation beyond any suicidal narcissistic impulse or at a minimum, the temporary shattering of the constitutive elements of our own self-hood, were we are led to confront the magnitude of unquantifiable currents of the non-discrete entities pouring through informational noise, that is, the demonological non-entity par excellence, the legion [50].

The demon responsible for diagonalizing us into the abyss is the faceless, historyless, identityless legion that pierces through our character armor which includes our capability for information coding from entropy and causes us to momentarily forget the why and how of our apparently finely-tuned cognitive processes. Here, in a certain way, we converge with Sabina Spielrein and Paul Ricoeur, the former who speaks of self-destruction as the result of a clash between the function of drives belonging to the psyche as something impersonal, and the psyche as the constitution of the ego that clashes with these drives, a clash that, for Spielrein, also explains the forgetting of selfhood in patients with early dementia, the fluctuation between drives, entropy, and the identity of the ego [51].

For the latter, Ricoeur mentions in his theological treatise, The Symbolism of Evil, in a Christian but no less interesting key, that nameless and faceless chaos is equivalent to evil and that salvation is equivalent to the act of creation from this chaos. However, he observes that evil does not correspond merely to demons as a force radically external to human beings, but to a forgetting that leads to our self-destruction as a consequence of diagonalization [52].

In other words, evil arises from human responsibility in the face of informational demonology, and it is entirely up to us what we want to do with the spear of noise and chaos: whether we decide to succumb to semantic apocalypse and therefore allow for the extermination of meaning, and therefore normativity as a whole through self-annihilation, or whether we want to do something based on the inevitability of our self-annihilation in time, even if momentarily through possession by diagonalizing demons. Could we then think of a case of strategic amnesia? With this, we would realize that there is a necessity for forgetfulness in as much it helps recalibrate, forgetting what is experientially given, forgetting the psychologistic burdens that we have placed as true beliefs and which would in turn lead us to the displacement of the impoverished models that seek to imprison us, and which in turn have currently imprisoned intelligence.

What are we to do then with the ethical responsibility in the face of chaos and modeling, and the contingent bundles of recursion that feed them? Through possession and strategical amnesia – as a form of induced psychosis after which we would find to be subjected to further objective constraints – we will find that the processes initially put to use as the building blocks in the history of intelligence are not to be taken as final or key to a finely weaved teleological narrative but as mere processes that can be further branched out and not nested within an absolute mythos [53]: sentience, sapience, cognition and language are some of the tools we currently have at hand under intelligence but virtually not the only ones. And only with this acknowledgement, we would be able to re-direct this history in order to shatter our transcendental roof to pieces when channeling intelligence as an infinite process beyond its current commodification through capital.

REFERENCES

[1] Ivar Frisch, Jenn Leung & Chloe Loewith, What We Do In The Shadows. 2025, Bianjie Research Group. Retrieved from: https://bianjie.systems/what-we-do-in-the-shadows

[2] Maks Valenčič, Psychotic Accelerationism. 2023, ŠUM #20. Retrieved from: https://www.sum.si/journal-articles/psychotic-accelerationism

[3] Bogna Koinor, The Dark Forest Theory of Intelligence. 2024, NYU Shanghai. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/xwq15qMHKjU?si=T55C19qDg6ZK6-3h

[4] Germán Sierra, The Artificial Unconscious. 2025, Bianjie Research Group. Retrieved from: https://bianjie.systems/the-artificial-unconscious

[5] Adrian Preda, AI-Induced Psychosis: A New Frontier in Mental Health. 2025, Psychiatry Online. Retrieved from: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2025.10.10.5

[6] Jacques Lacan, Écrits. 2006, Norton Publishing Company, 143.

[7] Evan Thompson, Dreamless Sleep, the Embodied Mind and Consciousness. 2015, OPENMIND 37(T), 7-8.

[8] We would be thinking here of a distribution of functions when in determinate cognitive states where weight would be given to certain faculties and less to others—to memory functions, for example, which would be more volatile in a state of so-called dreamless sleep—in order for the organism in question to be able to fully rest.

[9] Evan Thompson, Dreamless Sleep, the Embodied Mind and Consciousness. 2015, OPENMIND 37(T), 10.

[10] Blake Lemoine, Is LaMDA Sentient? — an Interview. 2022, cajundiscordian. Retrieved from: https://cajundiscordian.medium.com/is-lamda-sentient-an-interview-ea64d916d917

[11] In what follows, we will take explicit cues that synthesize arguments from Wilfrid Sellars’ Empiricism and Philosophy of Mind, John McDowell’s distinction and bridging between the space of concepts and the space of reasons as an actualization of Aristotle’s own distinction between first and second nature in Mind and World and Reza Negarestani’s Intelligence & Spirit, specifically extracting ideas from the chapter This I, or We or It, the Thing, Which Speaks (Objectivity and Thought).

[12] Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism. Zone Books, 1988, 14. We would also like highlight the similarities between Sellars’ insight on Bergsonian Durée in Science and Metaphysics where we see a demarcation and relationship between idealities as sorts of mediation (the transcendental ideality of scientific time in Kant and the temporality of the transcendental reality of states of affairs in Bergson), in which any case we can conclude there is no immediate to lived experience but a first level of mediateness: “It is possible (as Bergson saw) to insist on the transcendental ideality of scientific Time, while affirming the transcendental reality of states of affairs which are temporal in a related, but by no means identical, sense”. See: Wilfrid Sellars, Science and Metaphysics. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968, 37-38.

[13] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations. 2009, Blackwell Publishing, §5.

[14] Wilfrid Sellars, Science and Metaphysics. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968, 136.

[15] Yuxi Liu, The Perceptron Controversy. 2024. Retrieved from: https://yuxi.ml/essays/posts/perceptron-controversy/

[16] Frank Rosenblatt, The Design of an Intelligent Automaton. 1958, Research Trends, (6)2, 2.

[17] James Lighthill. Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey. 1972, Science Research Council, Artificial Intelligence: A paper symposium.

[18] The Fifth-Generation project sought to address the shortcomings of the past decades in AI research and, under a Promethean halo, be able to implement technologies that would permeate the entire social sphere in order to achieve the overall advancement of Japanese society and, subsequently, the Western world. The premise was simple, albeit ambitious: to develop hardware and software capable of handling AI complex enough for the systematic integration of functions related to reasoning, with a special focus on inference while being emphatic on the requirements and development of natural language. To this end, in 1981, the Japanese government provided funding and a pool of leading scientists and researchers for this purpose under the organization known as ICOT or the Institute for Computer Technology. In a general survey done by Feigenbaum and Shrobe we see the reach of this project: “Early ICOT planning documents [6] identify the following requirements: (1) To realize basic mechanisms for inference, association, and learning in hardware and make them the core functions of the fifth-generation computers. (2) To prepare basic artificial intelligence software to fully utilize the above functions. (3) To take advantage of pattern recognition and artificial intelligence research achievements, and realize man-machine interfaces that are natural to man. (4) To realize support systems for resolving the ‘software crisis’ and enhancing software production. A fifth-generation computer system in this early ICOT vision is distinguished by the centrality of (1) Problem solving and inference, (2) Knowledge-base management, (3) Intelligent interfaces”. See: Edward Feigenbaum, Howard Shrobe, The Japanese National Fifth Generation Project: Introduction, survey, and evaluation. 1993, Future Generation Computer Systems 9, 105-117 and Tohru Moto-oka, Fifth Generation Computer Systems (Proceedings). 1982, North-Holland Publishing Company.

[19] Sam Kriegman et al., Kinematic self-replication in reconfigurable organisms. 2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(49). Retrieved from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2112672118

[20] Abhishek Sharma et al., Assembly theory explains and quantifies selection and evolution. 2023, Nature, 622, 321-329.

[21] Manuel DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. 2006, Continuum.

[22] Matteo Pasquinelli, The Eye of the Master. 2023, Verso, 166.

[23] Ibid, 169.

[24] Ibid, 171.

[25] Ibid, 174.

[26] Reese M. Heitner, An odd couple: Chomsky and Quine on reducing the phoneme. 2005, Language Sciences 27, 3.

[27] John McDowell, The Engaged Intellect. 2009, Harvard University Press, 152-159.

[28] John Haugeland, Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea. 1985, MIT Press, 229-230.

[29] Hilary Putnam, Representation and Reality. 1988, MIT Press, 73.

[30] Ibid, 73.

[31] Ibid, 84.

[32] Ibid, 89.

[33] Saul Kripke, Philosophical Troubles: Collected Papers Volume 1. 2011, Oxford University Press, 23.

[34] David Marr, Vision. 1982, W.H. Freeman and Company, 347.

[35] Daniel D. Hutto, Erik Miyin, Evolving Enactivism: Basic Minds Meet Content. 2017, MIT Press, 58.

[36] Margaret Morrison, Reconstructing Reality: Models, Mathematics, and Simulations. Oxford University Press, 20.

[37] In reference to the inflationary reliance on modeling and simulation as proposed by David Chalmers in Reality +.

[38] Andrea Gambarotto, Hegel and the Evolutionary Dimension of Autonomy. 2024, teorema XLIII(2), 124.

[39] Mel Andrews, The Devil in the Data: Machine Learning & the Theory-Free Ideal. 2023, PhilSci Archive (Pre-Print),16. Retrieved from: https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/26075/

[40] Ibid, 6

[41] Ibid, 6

[42] Ibid,19

[43] Ibid,19

[44] James Ladyman, Reality minus minus. 2023, The Institute for Futures Studies, Stockholm. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/_0dc7qutyBc?si=zcr-EpTqg6NPnZ4K

[45] Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. 1967, MIT Press, 83-222.

[46] William Thomson, Kinetic Theory of the Dissipation of Energy. 1874, Nature 9, 441-444.

[47] A.A. Cavia, Shannon’s Demon. 2022, (&&&) TripleAmperSand. Retrieved from: https://tripleampersand.org/shannons-demon/

[48] Cecile Malaspina, An Epistemology of Noise. 2018, Bloomsbury, 73.

[49] Juan Comesaña, The Diagonal and the Demon. 2002, Philosophical Studies 110, 256.

[50] We have tried to develop some loose ends around this subject taken from Reza Negarestani’s seminar On the Practical Necessity of Having Demons. See: https://thenewcentre.org/archive/practical-necessity-demons/

[51] Sabina Spielrein, The Essential Writings of Sabina Spielrein. 2019, Routledge, 97-132.

[52] Paul Ricoeur, The Symbolism of Evil. 1969, Beacon Press.

[53] “Language, at first completely bound up with myth, becomes the vehicle for logical discourse and this in turn is the basis on which science evolves (…) but language leads not only to science; as poetry, language becomes art.” See: John Michael Krois, Cassirer: Symbolic Forms and History. 1987, Yale University Press, 79. We make a final note here in regard to the centrifugal movement observed by Krois that allows the detachment of language from mythos, leaving the door open for strategies against use and value through excess i.e. art as the non-useful when updating the rigid designator of transgression. Could intelligence—as a centrifugal tendency simultaneously acknowledging and shattering constraints—be compatible with unproductive expenditure? This issue will be developed in a forthcoming essay.

Federico Nieto is a researcher for The New Centre for Research & Practice and MPhil from National University of Colombia. Member of the publishing house and independent research group [Otros Presentes] and coordinator of the [CIDC] – Cuerpo de Investigaciones Críticas. Currently researching on cruelty as a normative undercurrent to the development of cognition and working on a PhD dissertation on the influence of Baruch Spinoza at the University of Warwick during the 90s and early 2000s. He can be reached at IG (@efenibot) and efenietod@gmail.com.