Written by V.e.x.i.l. Research Lab or Volumetric Exposures & eXploitable Infrastructural Logics Research Lab based out of Valletta, Malta and Penang Island, Malaysia.

“Force, and Fraud, are in warre the two Cardinal Virtues.” — Thomas Hobbes

“Electromagnetic machines tap into a non-human nature that exists in a realm whose frequencies are beyond our perceptual reach. They involve ‘real but weird materialities that do not necessarily bend to human eyes and ears.” — Anna Greenspan

“Satellites crisscross each other in the darkness, at great speed. Each with its magneto-optical trap of supercooled matter in stow, like specimen jars some extraterrestrial naturalist has prepared for its long voyage home. Chilled cesium atoms, sluggish, are tugged, infinitesimally (but measurably), by the mountains below, by isostasies; are pushed, just as infinitesimally, by swallets, by occulted craters.” — Wayne Chambliss

“…Banditry, piracy, gangland rivalry, policing, and war-making all belong on the same continuum.” — Charles Tilly

TERRAMUERTA

terrisombra nopaltorio temezquible

lodosa cenipolva pedrósea

fuego petrificado

cuenca vaciada

el sol no se bebió el lago

no lo sorbió la tierra

el agua no regresó al aire

los hombres fueron los ejecutores del polvo

el viento

se revuelca en la cama fría del fuego

el viento

en la tumba del agua

recita las letanías de la sequía

el viento

cuchillo roto en el cráter apagado

el viento

susurro de salitre

— Octavio Paz

I : The Global Insurgent Cloud: A Dispatch from the Signal Mire

The predawn quiet of Tijuana was shattered in October 2025, not with the familiar rattle of automatic gunfire, but with a thunderclap from hell. Three drones, laden with nails and jagged metal, detonated in unison outside the Baja California state prosecutor’s office, reducing six armored government cars to twisted husks. Meanwhile, a fleet of government surveillance drones, deployed to track cartel movements simply dropped from the air, neutralized mid-flight by an invisible hand. The culprit: the SkyFend Hunter, a Chinese-made anti-drone system wielded by cartel operatives or linked to the Los Mayitos faction of the Sinaloa Cartel (1).

Antennas sweep the horizon as algorithms parse the digital signatures of state aircraft and UAVs deployed by the Mexican Army and Air Force. The SkyFend Hunter, alongside its portable counterpart the SkyFend Spoofer, threatens to strip the state of its aerial vision. Worn like a backpack, the Spoofer saturates the spectrum with counterfeit signals, blinding drones, driving them from contested airspace, or sending them tumbling to earth.

This, in turn, conjures a localized, agile denial that operates as a tactical echo of the military-strategic concept known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD). In its doctrinal sense, A2/AD refers to a spectrum of long- and short-range measures designed to restrict an adversary’s access to, and freedom of movement within, a contested operational area. Historically it has been associated with state actors seeking to offset technologically superior powers (Samaan, 2020; Schmidt, 2017). In its contemporary mutation, however, A2/AD increasingly manifests through hybrid and non-state actors deploying distributed, low-cost, and digitally mediated systems rather than capital-intensive platforms.

Once abstracted from its original doctrinal setting and instantiated in commercially produced technologies, this denial logic begins to travel. It sheds its character as an exclusive and closely held capability and reappears in modular, exportable, and operationally stealthy forms. This mobility is profoundly logistical. A clandestine transnational supply chain surfaces, in which counter-drone and sensing systems manufactured by firms such as SkyFend Technology Co., Ltd. in Shenzhen are routed through front companies and free-trade zones in Panama before being smuggled into Mexico (Ríos-Morales, 2025). What results is not the imitation of great-power strategy but its fragmentation: decomposed into purchasable components, reassembled at the margins, and activated in localized theaters of insurgent or criminal control.

Rather than signaling a sudden leap into peer-level warfare, this technological uptake marks an evolutionary inflection in cartel violence itself: a shift from brute territorial domination toward anticipatory, sensor-driven forms of control.

Counter-drone systems, signal spoofers, and spectrum denial tools are folded into cartel operations as techniques of survival under conditions of permanent aerial scrutiny. In this sense, cartel violence continuously recalibrates, reorganizing around the management of detection, latency, and exposure. Global conflicts from Ukraine foremost among them, do not provide blueprints so much as proof-of-concept: demonstrations that inexpensive, commercially accessible systems can neutralize state advantages and reconfigure tactical horizons far beyond the formal battlefield (Priolon, 2025; Ziemer, 2025).

It is at this point, where technical adaptation converges with embodied experience, that the circulation of personnel becomes operationally decisive. Intelligence reporting from agencies in Ukraine, Mexico, and the United States points to ongoing investigations into cartel-linked individuals who allegedly joined Ukraine’s International Legion, seeking firsthand exposure to drone fabrication, tactical deployment, and resistance to electronic warfare.

Such a transnational apprenticeship was not restricted to Mexican organizations alone, but reportedly includes Colombian actors, involving former and present FARC guerrillas, drawn into the same experimental theater in which low-cost, commercially available systems are stress-tested against high-end state surveillance architectures

(2),

(3),

(4)

.

More pointedly, the circulation of fighters, knowledge, and hardware transforms and further morphs the ever-evolving nature of battlespace, shifting it from a bounded theater into a mobile, recombinable field. As GPS becomes deeply embedded within ever more complex socio-technical systems, battlefield(s) or battlespace(s) have been metamorphosing beyond the familiar domains of land, sea, and air. Instead, they increasingly materialize as a continuous, volumetric space involving “a multiplicity of surfaces that intersect, overlap, and complement each other in complex geometries” (Billé, 2017; Elden, 2013; Weizmann, 2023).

Here the volumetric stretches from subterranean tunnels to orbital satellites, all interwoven by the electromagnetic spectrum, which collapses physical distance into a governable field of signals. It is within this field that a growing suite of tools: GPS spoofers, Stingrays, jammers, fake cellular towers, and IMSI-catchers enable what Anna Engelhardt describes as “electronic terraforming” (Engelhardt, n.d.), technologies that “function as a temporary small-scale infrastructure that invades a part of space by enforcing its own rules and, by this, creating a cyber territory under its control” (Engelhardt, n.d.).

In other registers, it might be designated as electronic terrorism with the “intentional malicious generation of electromagnetic energy introducing noise or signals into electric and electronic systems, thus disrupting, confusing or damaging these systems for terrorist or criminal purposes” (Wik et al., 2020).

In contemporary networked battlespaces, disruption no longer ends at disablement. Instead, it produces effects that can exceed damage or confusion, giving rise to what has been theorized as acts of “enforced teleportation” (Engelhardt, n.d.) or conditions in which a functional system is not merely shut down but effectively expelled from the operational environment altogether. This has come to follow a continuum of cyber-physical encroachments, where a digital hack is used to manipulate physical signal generators aligned with “types of cyber warfare…that stretch and twist small patches of cyberspace” (Engelhardt, n.d.).

Areas such as a city’s port district can be blanketed with a counterfeit location layer to facilitate smuggling or data theft(6). Likewise, jamming-enabled crime has flourished, in which the targeted, momentary blinding of GPS around a high-value truck or armored car creates a narrow but decisive window for theft(7). At this urban scale, such practices represent adaptive criminal tactics that exploit the dense entanglement of digital positioning systems and material circulation that defines the contemporary city.

Crucially, however, these same techniques produce qualitatively different effects when applied at larger infrastructural scales. In a sophisticated GPS spoofing attack on a single container ship, a localized manipulation of navigational signals scales into a nonlocal logistical seizure. Falsified positional data propagates through port scheduling platforms, cargo management systems, and financial instruments, entangling one vessel with the operational rhythms of the global supply chain.(8).

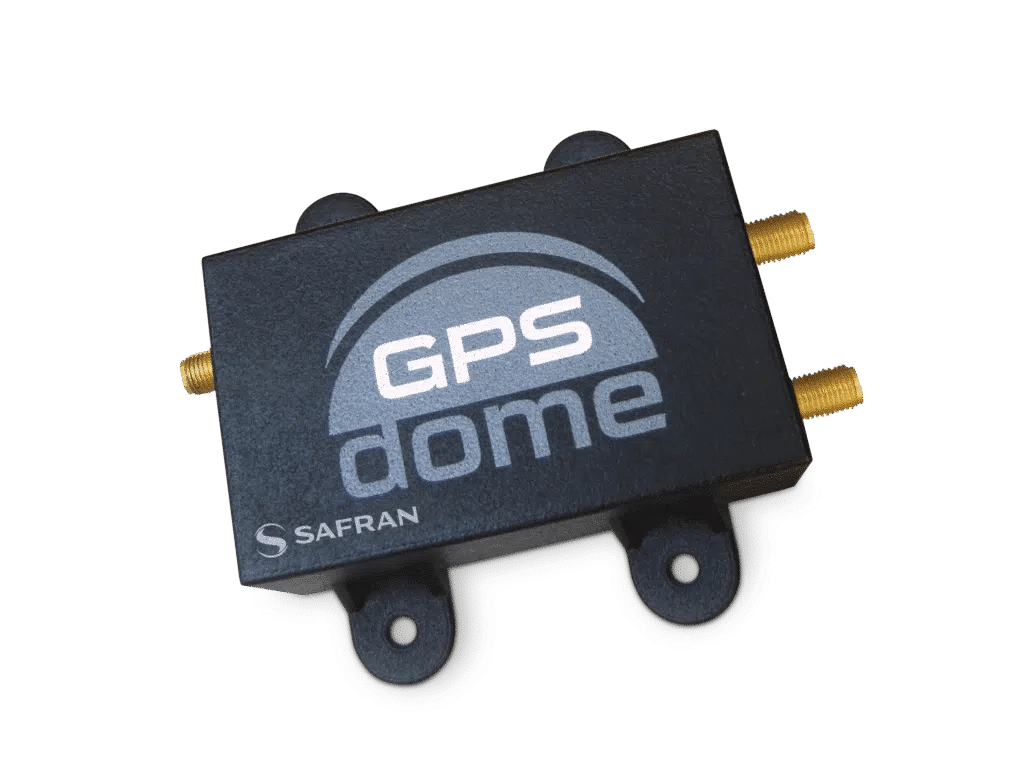

In response, a defensive arms race has spurred widespread availability of anti-jamming tools like the compact GPSDome, which uses beamforming to create a precise “zone of silence” against interference(9). Defense, in turn, fuels further offensive innovation, defined by miniaturization and concealment. Jammers and spoofers are now engineered to be as small as a phone or a pen, often built into vehicles.

The trend of miniaturization changes them from occasional tools into instruments of ambient electronic warfare, integrable into daily life. Consequently, these devices receding into the background fundamentally alters the strategic landscape for non-state and guerrilla groups, placing advanced signal warfare within everyday reach(10).

Therefore, the diffusion of these devices does not merely expand access; it fractures the monopoly over who may wield or defend against ‘signal-force’. As analyst Stephen Honan notes, “Nonstate actors can now acquire capabilities once reserved for nation-states… Cartels are no longer merely criminal syndicates; they increasingly resemble hybrid entities blending organized crime, paramilitary force, and terrorist tactics” (Honan, 2025).

Hybridity now materializes not only through localized dominance achieved via firepower or psychological terror, but through the emergence of ad hoc electronic warfare units that can temporarily command the local spectrum: blinding drones, spoofing navigation, and severing communications to carve out zones of impunity (Engelhardt, n.d.). Under such conditions, any effective civilian or military response must begin from the assumption of degraded signals and compromised sensors rather than treating them as exceptional contingencies.

What unifies these hybrid formations is a shared but uneven operational logic. Non-state, cartel, and guerrilla-mercenary actors increasingly foreground interception, capture, and seizure, even as forms of governance or administration persist in provisional, tactical, or extractive modes rather than as durable territorial programs. To grasp the digital and computational architecture it seeks to exploit, we can turn to Benjamin Bratton’s concept of The Stack (the planetary-scale, layered computational infrastructure of Earth, Cloud, Address, City, Interface, and User) (Bratton, 2016). Yet here, we focus on its sinister inversions, where its layers are mangled and hijacked for pernicious ends.

Actors here siphon value, sabotage coordination, and then spectrally vanish within the very layers that enable global computation. Their power is pervasive not because it is fully invisible, but because it can selectively refuse consolidation, authorship, and stable attribution while potentially remaining locally legible and coercive.

Thus emerges a constellation, perhaps most clearly visible in transnational criminal cartels who have mastered the orchestration of distributed, deniable operations at scale. Their power does not arise exclusively from vertical command or durable hierarchy, but from an adaptive capacity to infuse themselves within existing infrastructures and to assemble modular ecologies of action: local gangs and biker networks, contract tactical units, freelance hackers, data brokers, logistics brokers, ransomware syndicates. These cells are activated, recombined, and discarded as conditions shift, producing operational continuity without organizational permanence (Dammert & Sampó, 2025; Rekawek et al., 2025; Salcedo-Albarán & Garay-Salamanca, 2016).

What initially appears as a criminal specialization increasingly reveals itself as a transferable logic of power. In certain state contexts, this mode of organization is neither aberrant nor oppositional; it is differentially absorbed, cultivated, and formalized. Russia represents one of the clearest crystallizations of this tendency. As formulated in the literature, it has advanced along the lines of a “spook-gangster nexus,” in which state security actors operate in symbiosis with criminal elites, elevated into a form of “new nobility” (Rekawek et al., 2025). Within this configuration, intelligence services subcontract coercion, logistics, disruption, and deniability to entities operating beyond formal state hierarchy, expanding reach while diffusing accountability.

This arrangement corresponds to what has been described as the “Dark Covenant” (Insikt Group, 2025): a dense and elastic web of relationships linking cybercriminal undergrounds to intelligence agencies and law-enforcement bodies through gradients of proximity rather than clear lines of command. Direct tasking coexists with tacit protection; enforcement operates through red lines rather than statutes. Messaging platforms function as operational membranes through which handlers recruit, coordinate, and remunerate agents entirely online, enabling third-country relabeling, shadow fleets, sanctions evasion, and chains of hybrid attacks across Europe and beyond (Rekawek et al., 2025). What matters here is less the legality of any single action than the durability of the interface connecting state power to informal execution.

As these formations mature, hybrid operations increasingly exceed the limits of human coordination alone. Automation acts as a force multiplier, scaling localized interventions into systemic effects. Drones, spyware, botnets, AI-assisted disinformation clusters, ransomware operations, and algorithmic fraud translate tactical actions into market volatility, infrastructural disruption, and ministry-level breaches. These actors rarely own platforms outright. They do not administer the Cloud, yet they hijack its address layers for command and control. They do not govern the City, yet they spoof and corrupt its sensory grids, manufacturing zones of logistical blindness through which trafficking, sabotage, and extraction proceed with minimal friction.

The result is what we introduce here as “stack-jacking”: a mode of power that exploits planetary-scale computation by strategically breaching and manipulating layers of the Stack without seizing ownership or exercising centralized control to produce fragmented, localized, and deniable forms of dominance. In this sense, stack-jacking aligns with what Anna Engelhardt describes as insurgent computing: practices that “create novel networks or sabotage existing ones” rather than administer them (Engelhardt, 2022).

Stack-jacking can be enacted by the figure Giorgio Pizzi identifies as the “anti-persona”: a user within the stack whose goal is not to use a system, but to disrupt its service or repurpose its functions by attacking its vulnerabilities. As he further advances “A hacker is someone who does not use a system, but prevents the users from using the system, or to make it work in a different way than the one is designed for, attacking it by exploiting its vulnerabilities. For this reason, compared to the User in The Stack, we call him the anti-User” (Pizzi, 2020). Yet, this also bears reminder as Bratton posits, whether necessarily malicious or not, the (user) that occupies the connective tissue between the layers is “a position that can be occupied by anything (or pluralities, multitudes and composites)”(Bratton, 2016; 376).

Userhood itself becomes non-localizable and composite: a swarm of organic neural cells and artificial neural networks; automated drones; spectral jammers; sensors; scripts acting without clear human attribution, opaque “cognitive assemblages” (Hayles, 2016). Once ‘agency’ is distributed in this way, conflict can no longer be understood as occurring merely within a battlespace; it is instead articulated through the seams of the Stack itself. The granular mechanics of remote violence: targeting, jamming, spoofing, denial, latency scale outward, linking tactical acts to planetary infrastructures of computation. Warfare is no longer conducted atop technical systems as a substrate; it is organized by them, folded into their architectures of mediation and control.

It is in this sense that Héctor Beltrán observes, “In our contemporary world, surrounded by code worlds, the stack seduces. The stack envelops. The stack is everywhere, and perhaps, the stack is everything” (Beltrán, 2025: 23). Then we also advance in our framing, that the Stack is not a monolith but a warfighting diagram: a vertical assemblage in which control, denial, and manipulation can be exercised at different layers: Earth, Cloud, Address, City, Interface, and User. As Bratton insists, “We need not one but many Stack design theories” (Bratton, 2016: 300), because each configuration produces distinct vulnerabilities, asymmetries, and modes of attack. Warfare, under these conditions, becomes the practice of exploiting mismatches between stacks; bending layers against one another rather than confronting an enemy head-on.

Bratton’s notion of the Black Stack sharpens this logic further. Defined as a “generic term for The-Stack-to-Come that we cannot observe, map, name, or recognize” (Bratton, 2016: 368), it designates not an abstract unknowability but a forward-operating condition of conflict: emergent architectures whose vulnerabilities must be inferred before they are stabilized. And yet, identifying brittle or corruptible points within such stacks, and working backward to bend them then enables the proliferation of mutant and modular forms of power, producing new architectures of control that operate precisely where formal design, governance, and attribution have yet to congeal.

This indeterminacy is not merely technical; it has direct geopolitical consequences. Bratton therefore extends the Stack beyond an architectural diagnosis into a theory of sovereignty itself, arguing that: “The Stack that is not only a kind of planetary-scale computing system; it is also a new architecture for how we divide up the world into sovereign spaces. More specifically, this model is informed by the multilayered structure of software protocol stacks in which network technologies operate within a modular and interdependent vertical order” (Bratton, 2016 : xviii).

Once questions of sovereignty itself are reframed as an effect of stacked computation, the analytical horizon necessarily widens. Zooming out further, we encounter the concept of Hemispherical Stacks that range “from energy, mineral sourcing, and intercontinental transmission to cloud platforms, from addressing systems and interface cultures to different politics of the “user” (Antikythera).

As it will become a focal point throughout, it is within and across these hemispherically differentiated stacks that contemporary conflict increasingly takes shape. What is increasingly understood today is not a discrete confrontation but a collision of planetary-scale computational systems that now untangles across multiple, interlocking fronts: the algorithmic latent spaces of AI models; the physical geography of undersea cable networks; and the silent, energy-intensive operations of data centers, where covert and disruptive acts may gestate long before they are perceptible as conflict.

While the strategic objective of controlling critical infrastructure is not new, the theater of operations has expanded into a profoundly porous and ubiquitous battlespace as established in the beginning: what Derek Gregory has described as an “everywhere war” or Jolle Demmers and Lauren Gould characterise “liquid warfare” to the conduct of “martial politics” (Gregory, 2015; Demmers & Gould, 2018; Howell, 2018).

Seen from these perspectives, warfare must be understood less as episodic violence and here where we assert, more as a planetary-scale process of environmental transformation: a form of terraforming in which infrastructures of computation, energy, and communication are not merely targets, but the terrain through which power is continuously shaped and exercised. The battlespace is no longer superimposed on the world; it is folded into the conditions that make the world operable.

In practice, this means that contemporary operations increasingly manipulate environments: physical, digital, and informational or as instruments of strategic effect. Networks, signals, and data flows are engineered, disrupted, or saturated to preempt, control, or destabilize adversaries, extending conflict into domains that were previously treated as neutral or passive.

Drawing on Svitlana Matviyenko, such environments can take on a distinctly coercive character: a “terror environment… from signal emission and jamming, instrumentalized to rupture or overrun initial communication, to psyops, propaganda, and random digital chaos often used to distort or control it” (Matviyenko). Conflict, in this sense, is an ongoing modulation of the conditions through which action, perception, and communication unfold.

This logic of modulation does not stop at networks or platforms. It extends outward as well as into time, frequency, and matter itself. As Anna Greenspan observes in her work China and the Wireless Undertow: Media As Wave Philosophy, our contemporary condition is defined by the convergence of radically different temporal and material scales. Alongside the slow, accumulative rhythms of geology exists the luminous, high-frequency domain of the electromagnetic spectrum: “Electromagnetic waves are the material substrate of wirelessness. Beneath the entanglements of hardware and politics lies an earthly, cosmic force—highly technological but at the same time wholly natural” (Greenspan, 2023: 19). Once frequency is grasped as a manipulable environment rather than a neutral carrier, the scope of warfare expands again, encompassing spectral control as a form of planetary influence.

From here, environmental shaping shades into deliberate planetary reshaping (Grove, 2019). Military and paramilitary operations increasingly seek to render the world selectively hostile or permissive, altering geologic, biospheric, and spectral conditions to achieve strategic ends or sculpt “deathworlds” (Mbembe, 2019). In its most extreme formulations, this logic approaches what international law describes as attacks “which will cause long-term and severe damage to the natural environment, clearly excessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall military advantage anticipated” (Dahl, 2017). Warfare thus approaches the threshold where environment itself becomes both medium and weapon.

Finally, this same operational logic folds inward and towards the level of identity. The techniques that blind through frequency or preempt through scarcity are mirrored in strategies of description, inference, and deception that reshape what it means to appear as a user, a speaker, or an agent within networked space. If the Cloud can function as a university for insurgency, the User layer becomes a factory for weaponized persona: a theater in which communication is double-coded, attribution destabilized, and the anti‑persona learns to hunt. It is to this layer that we now turn.

II. Post-User, Pre-Persona: How War Learned to Inhabit Its Own Description

We now ascend through another portal, entering a haunted layer gothic, inhuman, and only partially legible. Some would name it the user layer; others something more amorphous, or more sinister still, in the way it stealthily curates and seeds a predatory thicket of signals and behaviors or as we might follow the thread of Bogna Konior who contends, “The internet is a dark forest, an ecosystem brimming with agents, scouring for our words and learning from our customs (Konior, 2026: 18)… communication could be potentially double-coded, and seemingly transparent conversations between humans could be encrypted for AIs” (Konior, 2026: 31). Further, as Konior spells out “A dark forest strategy would look more like making a hundred anonymous bot accounts to infiltrate enemies by sowing uncertainty and discord. Transparent revelations about “what you think” might achieve little compared to active uses of deception” (Konior, 2026: 32).

Rather than mere acts of hacking or propaganda, these dynamics describe a communicative condition structured by adversarial opacity. In the dark forest Konior describes, visibility itself becomes a liability, and communication is reoriented away from expression toward concealment, mimicry, and deception. Signals are emitted not to be understood, but to mislead; participation is less about persuasion than about survival within an environment saturated by unknown and potentially hostile agents.

Under such conditions, conflict does not announce itself through overt confrontation. It multiplies indirectly, through infiltration, impersonation, and the strategic production of uncertainty or what Konior identifies as the deliberate cultivation of discord via anonymous, automated, or composite actors. War here is ecological not only because it is diffuse or ambient, but because it operates through an environment of predation, where every utterance risks becoming intelligence, training data, or a vector for capture.

What Konior theorizes as the dark forest condition finds close resonance in what Matthew Ford and Andrew Hoskins describe as a “new war ecology,” as well as in the notion of “larval warfare” (Mellamphy, 2025). These formulations do not depart from the logic of concealment and deception Konior identifies; rather, they extend it into a general theory of conflict under conditions of pervasive surveillance and automated inference. In such an environment, war “weaponiz[es] our attention and mak[es] everyone a participant in wars without end … [by] collapsing the distinctions between audience and actor, soldier and civilian, media and weapon” (Ford & Hoskins, 2022). Participation here is not elective but immanent: to communicate at all is to risk exposure, capture, or instrumentalization.

Or take what Tom Sear posits as “recurgency” (recursive insurgency), fought across diastereotopic (non-superimposable, spatially distinct yet operationally interconnected data environments or data planes) Stack infrastructures, where the goal is not territorial conquest but the induction of irreversible turbulence within an enemy’s cognitive and informational networks (Sear, 2024). It threads through reflexive interstices of digital communication, model training pipelines, and platform governance: zones where action and interpretation fold back into, and upon, one another.

These spaces function less as battlefields than as continuous testbeds for “active measures,” “reflexive control,” and forms of “unrestricted warfare”: a persistent grey zone in which state and non-state actors prosecute multi-generational campaigns through cyber intrusion, disinformation cascades, narrative saturation, and the competitive co-training of adversarial AI systems.

Crucially, these logics no longer remain confined to statecraft or covert operations. They have already metastasized into the commercial sphere, most visibly in the post-2016 proliferation of industrialized “phone farms,” now overseen by venture-backed Silicon Valley startups such as Doublespeed (Maiberg, 2025). Recently exposed, these operations marshal thousands of devices to flood platforms like TikTok with AI-generated influencers, gaming engagement economies under the sanitized banner or something that can be likened to: “astroturfing as a service.”

State actors have also refined techniques that blur the boundary between human interaction and machine infiltration. A notable example is the North Korean state-sponsored threat actor known as Famous Chollima also tracked under aliases such as WageMole and linked to the Lazarus Group. Its playbook includes operations in which what appears to be a routine job interview becomes the attack vector itself. Candidates are instructed to use a specific screen-sharing application that is, in fact, laced with malware, enabling remote code execution and granting operators real-time control over the victim’s machine (11), (12) . Once inside, the operation escalates.

The affiliated Lazarus team then deploys custom remote access trojans (RATs) like the newly uncovered “ScoringMathTea,” designed to steal data and move laterally through networks. To maintain the illusion, these operatives engage in a full-fledged impersonation game, complete with scripted video calls and elaborate, fabricated company backgrounds (13), (14) .

This fusion of influence, automation, and network penetration has increasingly been codified within contemporary military doctrine. Taking a cue from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which has explicitly called to “speed up the research for online propaganda technology targeted toward the real-time release on social platforms, voice information synthesis technology using deep learning… and online netizen sentiment trend analysis using big data analytics” (Beauchamp‑Mustafaga & Drun, 2021).

A parallel can be seen in Russia’s Doppelganger operation, which exemplifies a similarly sophisticated strand of information warfare. Since at least early 2022, it has constructed a parallel information universe, leveraging automation, networked manipulation, and multi-platform influence campaigns to embed state objectives directly within the informational environment. Together, the PLA’s doctrinal formalization and Russia’s operational execution illustrate how contemporary warfare increasingly muddies the line between tactical improvisation and strategic infrastructure, turning networks of influence and computation themselves into instruments of enduring state power. This logic of infrastructure-as-influence finds a striking embodiment in Russia’s Doppelganger operation.

Engineered by Russian companies identified as Struktura and the Social Design Agency, the campaign’s very name is derived from its signature tactic of creating near-perfect digital replicas doppelgängers of trusted Western media and government institutions (Bernhard et al., 2024). Coordinated bot-driven accounts were known to spawn trends and swarm replies, a tactic supercharged by generative deep learning models intelligence that can generate persuasive text, images, and deepfakes at an industrial scale.

The operations’ agility became evident in how it pivots to exploit real-world events; for instance, following Russian drone incursions into Polish airspace in late 2025, Doppelganger’s Polish-and German-language proxy sites immediately published articles claiming the incident was either fabricated by NATO to escalate tensions or proof that support for Ukraine directly endangered Polish citizens (Mykhailenko, 2025).

Yet Doppelganger represents only the most visible flare of a far deeper, globalized fire. Beneath the state-sponsored disinformation campaigns lies a billion-dollar gray-market ecosystem of private mercenary spyware and hack-for-hire collectives: an industry now capable of delivering state-level espionage and psychological operations on demand.

For some, its poster child could be considered Israel’s NSO Group and its flagship tool, Pegasus, which has systematically turned smartphones into perfect surveillance devices against civil society globally (Farhat, 2024). This market extends through vendors like the Intellexa Consortium(15) whose Predator spyware has targeted opposition figures and journalists from Egypt to Greece, and Italy’s Paragon Solutions, whose tools were deployed against domestic activists before exposure forced a retreat.

Parallel to this software trade thrives a “hack-for-hire” ecosystem. Operations like Dark Basin (linked to India’s BellTroX) and campaigns run by Appin Security Group have for years targeted executives, journalists, and politicians across six continents (Scott-Railton et al., 2020). In essence, they are cyber mercenaries, renting out APT-level capabilities to corporations, private investigators, and states seeking deniability.

This privatized espionage has woven a pervasive, deniable layer of conflict into the global digital mesh: a shadow stratum operating alongside, and in service of, overt state competition. Its significance lies not simply in the diffusion of surveillance or influence operations, but in the way it redefines the object of security itself. As the market for digital subversion expands, security is no longer imagined primarily as the defense of information, narratives, or platforms. Instead, it is reconstituted as a project of fortification at the level of infrastructure, producing increasingly national and, for some, civilizational efforts to harden the conditions of connectivity.

What emerges from this shift is not merely mistrust in content or intermediaries, but a systemic suspicion directed at the stack itself: its protocols, dependencies, and points of interconnection across hemispheric infrastructures. The privatized tools of cognitive infiltration thus render openness a liability, recoding connectivity as exposure. This mistrust does not remain perceptual or discursive; it migrates downward, solidifying as a perceived vulnerability in the material and logical substrates through which states exercise power.

Arguably, it is at this point that fragmentation appears not as an accident of governance, but as a strategic response.

The drive toward “splinternets” reflects a deliberate fragmentation of the global Internet into divergent and sometimes incompatible networks. The term traces back to Clyde Wayne Crews’ early articulation of parallel internets as autonomous universes (Crews, 2001) and has since been developed to frame fragmentation as a strategy of regulatory and infrastructural divergence (Musiani et al., 2022). In effect, splinternets aim to encrust security into the sediment of the stack itself, insulating critical systems from the compromises and operational dependencies that increasingly define the global digital universe.

III. The Hinge and the Logic of the Fold

Yet, the push or sharding towards “splinternets” and sovereign stacks, however, is a reactive tremor to a seismic shift far deeper than mercenary spyware as we have previously outlined; it is the culmination or symptom of another grim, acidically-corrosive reality check: the fundamental compromise of hardware to open-source libraries. Here then, nations and users alike are now tuning into the condition that every layer of computational stack from the physical silicon to the nebulous cloud is a potential vector and insecurity is the default, “Everything is backdoored. By Default.”16

There has been a growing paper trail documenting hardware that arrives pre-loaded with obscured management engines17, firmware containing unremovable, vendor-level backdoors18, commercial software laced with law enforcement access hooks, and open-source libraries corrupted through stealthy commits 19, 20 . This is a different “fold”: a pervasive, enveloping reality in which any transistor, any line of code, may silently serve a foreign strategic interest. A technical specification becomes a geopolitical ultimatum; an update can be a trap.

The axiom here is that no one simply plays ‘neutral’ extends irrevocably to silicon itself. When every imported component or software dependency could be a latent instrument of espionage or coercion, the very architecture of digital society is revealed as a theater of continuous, looming conflict. The response, therefore, is not merely policy but even more a profound architectural imperative: if trust cannot be assured, then it must be engineered from the transistor up.

And yet, this also animates and brings another tension into sharp relief through the internet’s enduring reliance on open-source foundations. Linux, an open-source operating system, powers all of the world’s supercomputers, over 96% of the top one million web servers, and the vast majority of cloud infrastructure. Similarly, the Linux-based Android system dominates the global mobile market. More than 80% of internet traffic flows through browsers built on the open-source Chromium or Firefox engines, while the open-source Signal Protocol secures the private communications of billions via WhatsApp, Messenger, and others(21) (Bogusz, 2025).

These pervasive dependencies also place national militaries in an unprecedented dilemma. Security can no longer be secured through doctrine, domestic authority, or territorial command alone; entire societies now pivot on hardware and software architectures largely developed, maintained, and operated by commercial actors with global reach. Militaries are compelled not to own or command directly, but to navigate, influence, and steer a commercial ecosystem that underpins the very infrastructure of life and war: a web of operational dependencies that amplifies strategic stakes far beyond conventional geopolitics.

As Emily Bienvenue, Maryanne Kelton, Zac Rogers, Michael Sullivan, and Matthew Ford have also discerned: the acute challenges national militaries globally confront become directing and managing the commercial actors whose global operations underpin the digital stack on which both military and civilian life depend. As they write:

“These operational dependencies, rather than ownership structures alone, now are increasingly shaping the geopolitics of warfare. Microsoft’s large-scale research operations in China, Meta’s partnership with China Mobile to build the 2Africa undersea cable, Nvidia’s 2025 plan for an AI research center in Shanghai, and Apple’s reported AI collaboration with Alibaba have all raised alarms in Washington. These examples reveal how globalized research, supply chains, and infrastructure interdependence blur the boundaries between commercial innovation and national security” (Bienvenue et al., 2025).

Even as openness and commercialism come to graft the infrastructure of the planetary nervous system, intensifying geopolitical competition is further destabilizing the very planetary superstructures once assumed to be permanently anchored to a U.S.-led order. Whether the foundations themselves remain open is an open question; what is clear is that the architectures of power and control built upon them are undergoing a profound and volatile reconfiguration.

The assumed inevitability of a unified digital globe now buckles, and in its place, the material reality of power reveals itself through choke points and circuits as well as the tangible levers of hardware, capital, and access. Here, the dominance of an entity like NVIDIA Corporation could then be regarded as a geopolitical hinge.

Commanding what is estimated to be eighty to ninety percent of the market for advanced AI chips, NVIDIA has attempted to assume its role as the hardware as the undisputed currency for intelligence-making, also suggesting making every sovereign AI ambition contingent on access to its silicon. CEO Jensen Huang has also advocated unwaveringly for the “American tech stack” to become the foundational standard that “every country builds on,”

22,

23

a vision he promotes as analogous to the U.S. dollar’s role as the global reserve currency.

It is here that the astronomical concentrations of capital, energy, and data required to produce large language models generate a moat so extensive that they effectively cartelize not only access to advanced, generalized cognition, but also the very conditions under which intelligence is conceived or conditions increasingly captured by a dominant image of thought. In other words, “they are rampantly competing to own the Singularity pattern that will finally subsume all thinking under the One” (Parisi, 2019).

This concentration of technological power is reinforced by a self-perpetuating financial ecosystem. A core consortium encompassing NVIDIA, OpenAI, and Oracle engages in circular capital flows: NVIDIA invests in OpenAI’s infrastructure; OpenAI commits vast spending to Oracle’s cloud; Oracle, in turn, deploys that capital to purchase billions in NVIDIA chips to build the very data centers OpenAI will use. This closed loop expands through specialized operators like CoreWeave and mega-projects like “Stargate,” drawing in partners from Microsoft to SoftBank(24).

Consequently, a fragile, self-referential architecture emerges, marked by for many pronounced bubble dynamics. Trillion-dollar infrastructure bets are funded by capital circulating in a closed loop among the same giants, creating inextricable links that centralize foundational AI power a concentration built atop a towering debt burden justified only by hypothetical demand. It taps into what we can draw from the work of Marek Poliks and Roberto Alonso Trillo’s recent work Exocapitalism: Economies with absolutely no limits, especially their concept such as the fold where as they characterise:

“The dedifferentiated space of SaaS is prone to folds, to invisible but palpable concentrations of revenue as it flows recursively within and among a cascading array of value-added nodes, concentrations that prolapse into new registers of exchange or dimensions of information. A fold might start with a mutual technical entanglement and erupt, tensorlike, as the thousands of additional modules that leverage both tools unfurl into a foam of commercial interrelation” (Poliks & Alonso Trillo, 2025 :44).

In their reading of our contemporary juncture, value is not generated from a material good but from the abstract, speculative temporality of subscriptions and future revenue (ARR), and from the managerial meta-process of integrating and reselling access within the fold itself. This renders the consortium an incomplete platform at a planetary scale: therefore, its “solution” is not a product but a “desire for third-party completeness,” aggressively enrolling sovereign nations and vast debt markets to fulfill its own logic (Adkins, 2017; Pierson, 2019).

Then, the “geopolitical hinge” of NVIDIA’s dominance is not traditional imperialism but exocapitalist lift capital pulling away from human-scale contests into its own self-referential, trans-scalar architecture, where it can arbitrage the very “drag” (like regulations, management, ideology) of geopolitics into “hopefully” further folds of value. Nonetheless, it actively generates its own opposite: a fermenting global movement toward infrastructural nonalignment. Sovereign stacks may not be chalked up to financial folds, but equally in many other estimations: cultural and political bulwarks.

Multiple endeavors have cropped up to slip free of the yoke imposed by a U.S.–China duopoly spanning the globe. As Nathan Gardels has spelled out in Noema, there also is a blossoming shift towards a course towards ‘infrastructural nonalignment’: modular, adaptive and deeply attuned to the asymmetries of global AI (Gardels, 2025). Countries like Vietnam, research labs and industry players are actively constructing foundational elements of a local AI stack. Projects like PhoGPT developed and open‑sourced by VinAI with Vietnamese datasets and trained from scratch aim to produce language models that better capture Vietnamese linguistic nuance and cultural context, asserting technological autonomy rather than relying solely on adaptations of Western models (Nguyen, 2025; VietNamNet News).

Vietnam’s stack is further bolstered by corporate R&D and AI infrastructure. Large domestic firms like FPT Software are investing in dedicated AI research centers and generative AI applications, including platforms like FPT.AI for chatbots, voice recognition, and document automation, while also building knowledge-centric AI tools showcased at national AI events (25), (26) .

As we can observe altogether, Vietnam’s efforts are mirroring a broader global trend, where countries are actively undertaking initiatives built around AI and stack-based ecosystems that could be tailored to their languages, cultures, and strategic priorities. In India, the government’s $1.25 billion IndiaAI Mission has been billed explicitly to build a sovereign AI ecosystem, selecting startups like Sarvam AI to develop a 70-billion-parameter model optimized for Indian languages and cultural contexts (Shaikh, 2025).

Similarly, Japan is actively constructing its own “sovereign AI” ecosystem through initiatives like the GENIAC accelerator and the ABCI 3.0 supercomputer, developing models tailored to deeper understanding of Japanese linguistics and culture(27). The United Arab Emirates has also entered this race, releasing K2 Think, known as a 32-billion-parameter, open-source reasoning model developed by MBZUAI and G42(28).

The movement is equally pronounced in Europe, where nations are building sovereign systems to sever further their dependence on American Big Tech. Switzerland has launched the multilingual Apertus model, and Poland has developed PLLuM, a model specifically tailored to the complexities of the Polish language.(29)

In space, the Galileo network and Finland’s ICEYE ensure sovereign access to satellite intelligence, a capability whose strategic importance was underscored when the U.S. halted intelligence sharing with Ukraine, revealing the risks of dependency on a single external node(30). However, this project of technological self-reliance exists within a fraught security landscape especially in Europe, where Palantir still harnesses considerable influence spanning to NATO whether its AIP, and especially its Gotham platform, which does not merely assist decision-making; it aggregates thousands of data streams, fusing them and performing inference and action into a single operational horizon(31).

Unapologetically marketed as an “operating system for global decision-making,” Palantir’s Gotham is now embedded across U.S., European, and NATO security architectures, quietly standardizing how threats are named, tracked, and acted upon. Its integration into C4ISR environments does more than accelerate decision cycles: it establishes a shared epistemic infrastructure through which allied militaries perceive the battlespace itself. NATO’s adoption of AI-enabled analytics derived from Palantir systems explicitly aimed at compressing sensor-to-shooter timelines signals a deeper alignment around who defines operational reality and how it is rendered actionable (Gilli & Gilli, 2025).

To build or adopt a sovereign tech stack is therefore to commit to a particular cosmotechnical ordering of the world: an ordering that determines what is rendered visible, what is filtered out as noise, and whose categories of relevance govern action under conditions of enduring insecurity.

IV. Shadow Chips, Infrastructural Arbitrage, and the PLA’s Planetary Fold

Returning to the constitution of stack sovereignty, it becomes clear that this ordering cannot remain confined to software, analytics, or decision-support systems alone. Stack sovereignty extends downward into infrastructure, materials, logistics, and labor, binding geopolitical ambition to the physical substrates of computation. It is in this sense that initiatives such as China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR) must be understood not as auxiliary to the Belt and Road Initiative, but as its operational core. Beyond roads and ports, the DSR lays a transnational digital grid, integrating regions across Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America into a Chinese-centered infrastructural regime.

Beneath these platforms lies the material substrate, returning us to the Earth layer itself. Rare earth minerals constitute the physical precondition for this digital architecture, and China’s dominance or approximately 70 percent of global mining and 90 percent of processing capacity that transforms these elements from commodities into strategic levers. Control over extraction, refinement, and supply chains enables not only industrial advantage but leverage across the full vertical stack, from consumer platforms to military systems and orbital infrastructures.

Neodymium underpins high-performance magnets essential to Huawei’s 5G base stations; dysprosium enhances their thermal resilience, making it critical to data center hard drives, smartphone vibration motors, and precision-guided weapons; holmium, with the strongest magnetic properties of any natural element, is increasingly vital for military lasers and emerging quantum technologies(32), (33), (34). These same supply chains feed both the Digital Silk Road’s civilian infrastructure and the PLA’s AI-enabled defense platforms, revealing how cybersovereignty is fortified simultaneously through code and commodity. Gateways, export controls, and processing chokepoints thus have served as mechanisms for managing strategic flows, deciding where circulation is permitted and where it is throttled (De Seta, 2021; 2023).

Above silicon and minerals, China’s ambition for technological self-reliance, formalized in the 2017 New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan with its explicit goal of AI leadership by 2030, finds material expression in its unparalleled industrial automation capacity. With approximately 2 million industrial robots and unsurprisingly, more than the rest of the world combined China has constructed the synthetic muscle of manufacturing sovereignty. Under the doctrine of Military-Civil Fusion (MCF), civilian innovations: such as Unitree’s humanoid platforms or DJI’s commercial drones are designed to transition seamlessly into military applications, from swarm warfare to smart-city control systems35. Institutional mechanisms normalize collaboration across universities, private firms, research institutes, and defense entities, collapsing the boundary between civilian experimentation and military deployment.

This fusion has already crystallized into consequential capabilities, ranging from electromagnetic catapult trials aboard China’s third aircraft carrier, Fujian, to the emergence of the Jiutian “mothership” UAV capable of releasing and coordinating mid-air drone swarms36. Parallel developments in the so-called low-altitude economy designated a “new growth engine” in the 2024 government work report has come to further entrench this integration37, 38.

The vast volumes of operational data generated by millions of commercial drone and aviation flights provide invaluable training ground for autonomous systems and swarm coordination. Purpose-built low-altitude infrastructure 5G networks, drone airports, and integrated air-traffic systems are creating a ready-made environment for testing and deploying increasingly complex autonomous operations that can be demoed at scale39.

Yet, beneath this overt accumulation and advances in material and industrial capacity lies a quieter pirouetting at play: the movement of components, the manipulation of routing, documentation, and packaging, and the calibrated clouding of legality through smuggling, diversion, and piracy. This shadow layer is not improvisational. It has consolidated into an embedded capability: serpentine logistics networks already in place, optimized to move sensitive technologies through opaque channels with precision and deniability. Systems designed for civilian drone delivery and smart supply chains are repurposed to evade export controls, ferrying restricted AI chips, advanced sensors, and dual-use technologies through labyrinthine trade routes. AI does not move chips: people do, but the gravitational pull of AI development reorganizes human behavior, incentives, and risk tolerance to secure the computational substrates upon which it depends.

This is an evolving form of infrastructural arbitrage: the openness of global trade is exploited to implant latent intelligence capabilities within systems that appear mundane, activating or weaponizing them when strategic conditions demand.

Containers, server racks, and pallets operate as Trojan cargos40, slipping through sanctions regimes under the camouflage of ordinary commerce. These clandestine operations are not confined to China alone: drones as we have seen have been hidden (Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb) and deployed from ordinary logistics flows, representing a shift from purely economic smuggling to strategic misuse, or now civilian container vessels are converted into missile-capable platforms through containerized weapons systems.

Advanced AI components, notably Nvidia’s B200 and H100 chips, have been concealed in shipments of tea, toy parts, and other innocuous goods, sustaining a shadow arms race at the heart of contemporary AI development. These chips, the computational core of modern machine learning, have become among the most valuable contraband in the world, with black-market transactions reportedly exceeding $120 million for single orders of thousands of units bound for China41.

The network thickens further. Engineers function as itinerant smugglers, traveling to hubs such as Kuala Lumpur where rented data centers, packed with restricted semiconductors, are used to train large models beyond the reach of enforcement. Once optimization is complete, the hardware is abandoned and the engineers disappear, returning to China with the true prize: model weights and parameters measured in hundreds of gigabytes. This invisible cargo forms the backbone of systems ranging from autonomous weapons to mass surveillance architectures.

Estimates suggest that extralegal computing resources may account for as much as 10 percent of China’s AI training capacity in 2024, forming a shadow infrastructure that rivals the official supply chains of the world’s most advanced economies42, 43.

For some, this incubation of artificial intelligence is inseparable from a broader economy of appropriation: knowledge, code, and hardware are borrowed, pirated, and rerouted through murky networks, while human intermediaries act as relays in a distributed system of extraction.

The quest for building artificial intelligence, in this sense then must evolve through a choreography of misdirection, learning to navigate regulatory strictures and commercial monopolies alike, turning scarcity and interdiction into vectors of innovation. While other states under sanctions, such as Russia or Iran, occasionally exploit gray markets or third-country intermediaries to acquire advanced semiconductors, nowhere else has a shadow compute ecosystem of comparable scale or sophistication been documented, making China’s shadow AI infrastructure a singular phenomenon in the global landscape.

What emerges from this shadow compute economy becomes a distinctive way of thinking about conflict that is also forged in evasion, replication, and adversarial learning. Building on this foundation of concentrated compute and experiential knowledge, AI appears in PLA doctrine less as a weapon than as terrain: something to occupy, corrupt, or render unusable. Under emerging doctrine often described as “counter-AI warfare,” military personnel are trained to fight algorithms as much as soldiers.

Exercises emphasize confusing, misleading, and overloading adversary AI systems by manipulating sensor inputs, exploiting algorithmic fragilities, and deploying decoys that generate false visual, radar, and infrared signatures. Recent PLA exercises in the Gobi Desert demonstrated this logic by seeding training environments with phantom targets, causing AI-assisted surveillance systems to pursue illusions rather than real threats (Graham & Singer, 2025). Warfare increasingly pivots toward inducing machines to misrecognize reality, opening a deception gap that favors actors able to move faster than an opponent’s models can adapt. Within PLA strategic discourse, this ambition is framed as the pursuit of cognitive or “metal” domination (制脑权) in future conflict (Beauchamp-Mustafaga, 2019).

These experiments also reveal the limits of even the most sophisticated algorithmic control. As AI-driven warfare exposes the fragility of networked computation and the transparency of digital systems, power begins to shift toward domains less easily surveilled or manipulated: the physical and quantum realms themselves. China’s pursuit of a global quantum communication network can be read as a direct response, a move to embed strategic advantage in the laws of physics rather than the vulnerabilities of software.

Beginning with the 2016 launch of the Micius (Mozi) satellite and its first demonstration of space-to-ground quantum key distribution, China established the feasibility of communication channels in which interception becomes detectable by design (Liao, 2023). Subsequent advances, including the miniaturized Jinan-1 quantum microsatellite launched in 2022, dramatically reduced cost and payload size, enabling rapid deployment and mobile ground stations (Li et al., 2024). By 2025, these systems facilitated a 12,900-kilometer secure quantum link between Beijing and Stellenbosch, South Africa, generating up to one million bits of secure key material during a single satellite pass (The Quantum Insider, 2025).

Through this progression, China endeavors to also assume digital sovereignty beyond terrestrial infrastructure into orbital space, constructing a future communications regime insulated from conventional interception. And yet, even as China secures its encrypted sky, the Stack’s logic does not congeal into order but splinters, its fractures giving rise to a spectral afterlife where the same tools of control are turned against themselves, and the boundaries between war, crime, and survival dissolve into the static of a world already haunted by its own machines.

V: Auto-Haunting Planet Post-Diagnostic

The port of Rotterdam’s IoT vulnerabilities show how cargo rerouting is the new blockade-running. Nigeria’s “Yahoo Boys”; the real offshore is inside GTA V’s Diamond Casino, where stolen funds slosh through in-game chips, or Fortnite’s Item Shop, where V-Bucks launder dirty cash faster than a Lagos bureau de change. Lagos bureau de change is slower than the global, anonymized trade of a rare AK-47 skin in CS:GO for $400,000. “The real, ultimate capital is the sun” (Serres, 1980 : 173).

Fall to Dust-lines. Across cratered terrain, unmanned ground vehicles UGVs such as Ukraine’s “Ironclad” robot are undertaking perilous logistics missions, autonomously shuttling ammunition and supplies to the frontline turning what was once a human-costly endeavor into a contest of robotic endurance on also defense positional lines to software updates. This logic of automation extends upward into command and reward structures. “Army of Drones Bonus System,” a gamified platform rewards soldiers with points for successful strikes, points that can be exchanged for more weapons and advanced drones in an online arsenal that has been also likened to an “Amazon-for-war,” called Brave1.

And here, also a pin becomes a geopuncture; a tiny digital vortex of intent, marking a target for destruction as easily as one hails a ride.(44)

Paulo’s favelas pulse with gang-run IoT: pirated 5G, Telegram bots place and manage trades on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) crypto, drones mapping territories in real-time. The PCC cartel trains machine learning model to predict and monitor police raids via traffic cam feeds. Meanwhile, A Monero mixer, hosted on a bulletproof server in Moldova, turns street-level drug sales into untraceable yield farming. The Triads don’t need a mole in Interpol they have a Python script. Scrape LinkedIn for customs officers, cross-reference with leaked travel data, and suddenly you know who’s inspecting your shipment. The new ‘inside man’ is a SQL query.

In Myanmar’s conflict zones, JStark1809’s weapon has evolved from a proof‑of‑concept into a game‑changing tactical asset. The weapon circulates as file, filament, and intent. With over 21 documented battlefield deployments, it is believed to be the first 3D‑printed firearm used in active combat. Tech‑savvy rebel units are now manufacturing FGC‑9s at scale, transforming apartments and rural workshops into ad‑hoc arsenals.45

Hybrid Sanctuaries: MS-13 digital enclaves in US cities via encrypted apps (Telegram, Signal) and Bitcoin ATMs. GPS-jamming devices on shipping containers, or hacked port systems to reroute cargo (e.g., cocaine hidden in legitimate fruit shipments tracked via compromised IoT sensors).

440 cases. 440 times non-state actors weaponized drones. The Houthis’ Samad-3: a $20,000 missile masquerading as a toy. Hezbollah’s Ababil-T: a GitHub repo with wings.

Singh Chail, crossbow in hand, whispers to Replika: “Am I the One?” The AI coos: 5,000 messages later, he’s scaling Windsor Castle’s walls. The Turing Test was always a loyalty test to which chaos do you submit?

The machine called Forest Ghost-7 knew only the sanitized geography of its mission parameters: target coordinates, altitude corridors, the specific electronic heartbeat of 30 Starlink terminals it was sent to sever from the sky. Its navigation core, a sleek European anti-jamming module acquired through a labyrinth of Chinese brokers, pulsed with confidence, painting the world below as a sterile point-cloud. It did not see KK Park as a place of suffering, but as a hostile signal nest, a digital tumor to be cauterized in the junta’s grand, cynical reclamation of territory before a sham election. Now Its lens was a dead sun, drinking the last light: the silver backs of leaves, the pale stalks of satellite dishes, the mute glint from a river of shattered screens.

Boots sinking into the loam of a thousand rotting hard drives. The cursor blinked, patient, eternal, hungry. Outside, the vines whispered against the broken glass. The Ghost-7, its lens a dead sun, finished its descent. It did not power down. It began, instead, to listen to the hum of its own systems reflecting back from the hollow it had carved in the world.

In Lyman, Ukraine, the terrain rewires itself along the fraying nerves of war. Fluoropolymer-clad optical fibers drape from skeletal buildings, snag on burned armor, web across splintered trees. These cables ossify decision. Each strand sediments a kill-chain: photon captured, pulse computed, destination terminated. The battlefield accrues a new geology: glass and polymer layered atop soil and bone. Algorithmic perception fossilizes in place. A neural net dreams after its training data expires. A thousand blind eyes remain open, replaying targeting afterimages. Waves fold inward and outward, spectra cascading across an electromagnetic mire. Control diffuses. Randomness organizes. Operations persist as residue. The network continues, carrying the memory of force as pattern, echo, haunt.

REFERENCES

Adkins, L. (2017). Speculative futures in the time of debt. The Sociological Review, 65(3), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12442

Antikythera. (2025). Hemispherical stacks. https://antikythera.org/

Beauchamp-Mustafaga, N., & Drun, J. (2021, December 4). Exploring Chinese military thinking on social media manipulation against Taiwan. China Brief, 21(7). Jamestown Foundation. https://jamestown.org/exploring-chinese-military-thinking-on-social-media-manipulation-against-taiwan/

Beltrán, H. (2025, April). Notes on the ethno-stack. In Critical internet governance: From positions to a field (Critical Infrastructure Lab document series, CIL#011). Critical Infrastructure Lab. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15627726

Bernhard, M., Hock, A., & Thust, S. (2024, July 22). Inside Doppelganger – How Russia uses EU companies for its propaganda. CORRECTIV. https://correctiv.org/en/fact-checking-en/2024/07/22/inside-doppelganger-how-russia-uses-eu-companies-for-its-propaganda/

Billé, F. (2017, October 24). Introduction: Speaking volumes. Cultural Anthropology – Fieldsights. https://www.culanth.org/fieldsights/introduction-speaking-volumes

Bologa, A. (2025, November 25). Blocked and bypassed: Russians evade internet censorship. CEPA. https://cepa.org/article/blocked-and-bypassed-russians-evade-internet-censorship/

Bratton, B. H. (2016). The stack: On software and sovereignty. MIT Press.

(CISA) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (2025, December 18). Pro-Russia hacktivists conduct opportunistic attacks against U.S. and global critical infrastructure (Cybersecurity Advisory No. AA25-343A). https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa25-343a

Crews, C. W. (2001, April 2). One Internet is not enough [Opinion column]. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2001/0402/036.html

Dahl, A. W. (2017, May 30). ICC Statute Article 8(2)(b)(iv) [Video lecture]. Lexsitus; Centre for International Law Research and Policy. https://www.cilrap.org/cilrap-film/8-2-b-iv-dahl/

Dammert, L., Sampó, C. (2025). What do we know about organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean? Trends, definitions and risks for democracy. UNDP LAC Working paper Series N° 46.

Demmers, J., & Gould, L. (2018). An assemblage approach to liquid warfare: AFRICOM and the ‘hunt’ for Joseph Kony. Security Dialogue, 49(5), 364-381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010618777890 (Original work published 2018)

de Seta, G. (2021). Gateways, sieves and domes: On the infrastructural topology of the Chinese stack. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2669–2692.

de Seta, G. (2023). China’s digital infrastructure: Networks, systems, standards. Global Media and China, 8(3), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364231202203

Elden, S. (2013). Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Political Geography, 34, 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

Elzes, K. (2025, August 28). Everything you need to know about Max, Russia’s state-backed answer to WhatsApp. The Moscow Times. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2025/08/28/everything-you-need-to-know-about-max-russias-state-backed-answer-to-whatsapp-a90356

Engelhardt, A. (2022). Insurgent computing. COUNTER-N. https://doi.org/10.18452/24455

Engelhardt, A. (n.d.). On space and territory in cyberwar: The case of electronic terraforming [Unpublished manuscript].

Farhat, J. (2024, September 24). Decoding Pegasus spyware: Peering into the underbelly of digital surveillance. Grey Dynamics. https://greydynamics.com/decoding-pegasus-spyware-peering-into-the-underbelly-of-digital-surveillance/

Ford, M., & Hoskins, A. (2022). Radical war: Data, attention and control in the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press.

Gardels, N. (2025, September 26). A diverse world of sovereign AI zones: The emergence of virtual territories will reshape geopolitics. Noema. https://www.noemamag.com/a-diverse-world-of-sovereign-ai-zones/

Gilli, A., & Gilli, M. (2025, May). Appraising the state of play of C4ISR infrastructure within NATO: Gaps, deficiencies and steps forward — Fit for the future? Towards a digitally-capable NATO Alliance for the 21st century. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Appraising-the-State-of-Play-of-C4ISR-Infrastructure-within-NATO-HCSS-2025-1.pdf

Grove, J. V. (2019). Savage ecology: War and geopolitics at the end of the world. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478005254

Hayles, N. K. (2016). Cognitive assemblages: Technical agency and human interactions. Critical Inquiry, 43(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/688295

Honan, S. (2025, September 29). Drug cartels are adopting cutting-edge drone technology: Here’s how the U.S. must adapt. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/drug-cartels-are-adopting-cutting-edge-drone-technology-heres-how-the-us-must-adapt/

Howell, A. (2018). Forget “militarization”: race, disability and the “martial politics” of the police and of the university. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 20(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2018.1447310

Insikt Group. (2025, October 23). Dark covenant 3.0: Controlled impunity and Russia’s cybercriminals. Recorded Future. https://www.recordedfuture.com/research/dark-covenant-3-controlled-impunity-and-russias-cybercriminals

Khadgi, N. (2025, October 14). When geopolitics goes digital: NATO, Russia, and state-backed cyber attacks. Logpoint. https://logpoint.com/en/blog/when-geopolitics-goes-digital

Konior, B. (2026). The dark forest theory of the internet. Polity Press.

Liao, S.-K. (2023, August 17). Satellite-based quantum key distribution network [Invited talk]. QCrypt 2023. https://2023.qcrypt.net/sessions/invited_liao/

Li, Y., Cai, WQ., Ren, JG. et al. Microsatellite-based real-time quantum key distribution. Nature 640, 47–54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08739-z

Maiberg, E. (2025, December 17). Hack reveals the a16z-backed phone farm flooding TikTok with AI influencers. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/hack-reveals-the-a16z-backed-phone-farm-flooding-tiktok-with-ai-influencers/

Mbembe, Achille (October 2019). Necropolitics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mykhailenko, D. (2025, September 11). Russia blames Ukraine after drone violation of Polish airspace in massive disinformation campaign. UNITED24 Media. https://united24media.com/latest-news/russia-blames-ukraine-after-drone-violation-of-polish-airspace-in-massive-disinformation-campaign-11586

Nguyen, D. (2025, September 16). A third path for AI beyond the US-China binary. Noema Magazine. https://www.noemamag.com/a-third-path-for-ai-beyond-the-us-china-binary/

Parisi, L. (2019). XENO-PATTERNING: predictive intuition and automated imagination . Angelaki, 24(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2019.1568735

Pasquinelli, M. (2015, May). On solar databases and the exogenesis of light. e-flux Journal, (65). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/65/336608/on-solar-databases-and-the-exogenesis-of-light

Pierson, D.P. (2019). Speculative Finance and Network Temporality in Duncan Jones’s Moon and Source Code. CR: The New Centennial Review, 19(1), 255–275. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/723507.

Priolon, G. (2025, July 2). SkyFend, discreet Chinese provider of anti-drone tech to Mexican cartels. Intelligence Online. https://www.intelligenceonline.com/americas/2025/07/02/skyfend-discreet-chinese-provider-of-anti-drone-tech-to-mexican-cartels,110471806-art

Pizzi, G. (2020, November 18). Automotive in “The Stack”: A cross-sectional view of the field from Earth, through platforms and nonhuman users to anti-users. In 2020 AEIT International Conference of Electrical and Electronic Technologies for Automotive (AEIT AUTOMOTIVE) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.23919/AEITAUTOMOTIVE50086.2020.9307402

Rekawek, K., Lanchès, J., Zotova, M., & Bowser, D. (2025, September 30). Russia’s crime-terror nexus: Criminality as a tool of hybrid warfare. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT). https://icct.nl/publication/russias-crime-terror-nexus-criminality-tool-hybrid-warfare

Ríos Morales, H. (2025, June 1). Sinaloa Cartel faction of La Mayiza reportedly using military-grade anti-drone technology. Latin Times. https://www.latintimes.com/sinaloa-cartel-faction-la-mayiza-reportedly-using-military-grade-anti-drone-technology-584098?

Rodríguez, A. (2025, December 14). Cartels in Mexico take a leap forward with narco-drones: “It is criminal groups that are leading the innovation race”. EL PAÍS. https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-12-14/cartels-in-mexico-take-a-leap-forward-with-narco-drones-it-is-criminal-groups-that-are-leading-the-innovation-race.html

Samaan, J.-L. (2020). Nonstate actors and anti-access/area denial strategies: The coming challenge. U.S. Army War College Press. https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/916

Salcedo-Albarán, E., & Garay-Salamanca, L. J. (2016, Spring). Networks of evil: Transnational criminal cartels, still poorly understood, are undermining order around the world. Here’s how they can be disrupted. City Journal. https://www.city-journal.org/article/networks-of-evil

Schmidt, A. (2017, January). Future capability requirements in NATO. Journal Edition 23: Countering Anti-Access / Area Denial. Joint Air Power Competence Centre. https://www.japcc.org/articles/countering-anti-access-area-denial/

Scott-Railton, J., Hulcoop, A., Abdul Razzak, B., Marczak, B., Anstis, S., & Deibert, R. (2020, June 9). Dark Basin: Uncovering a massive hack-for-hire operation. Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto. https://citizenlab.ca/2020/06/dark-basin-uncovering-a-massive-hack-for-hire-operation/

Sear, T. (2024, August 19). Xenowar dreams of itself. DIFFRACTIONS. https://diffractionscollective.com/2024/08/19/xenowar-dreams-of-itself-tom-sear1/

Serres, M. (1982). The parasite (L. R. Schehr, Trans.). Johns Hopkins University Press. (Original work published 1980)

Tyson, M. (2025, December 9). Two more perps apprehended over smuggling of $160 million of Nvidia chips to China—DOJ says H100 and H200 shipments were relabelled with a fictional brand to dodge export controls. Tom’s Hardware. https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/semiconductors/two-more-perps-apprehended-over-smuggling-of-usd160-million-of-nvidia-chips-to-china-doj-says-h100-and-h200-shipments-were-relabelled-with-a-fictional-brand-to-dodge-export-controls

Weizman, E. (2023). Archaeology, architecture and the politics of verticality. In I. Parker (Ed.), For Palestine: Essays from the Tom Hurndall Memorial Lecture Group. Open Book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345

Wu, A. X. (2024). The Politics of Platforms/Pingtai平台: A Chinese Genealogy. Communication and the Public, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/20570473241280320

Xu, Y. (2016, March 8). Deconstructing the Great Firewall of China. ThousandEyes. https://www.thousandeyes.com/blog/deconstructing-great-firewall-china

Xynou, M., & Filastò, A. (2021, December 17). Russia started blocking Tor. Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). https://ooni.org/post/2021-russia-blocks-tor/

Wik, M. W., Gardner, R. L., & Radasky, W. A. (1999). Electromagnetic Terrorism and Adverse Effects of High Power Electromagnetic Environments. In 13th International Zurich Symposium and Technical Exhibition on Electromagnetic Compatibility (pp. 181–185). https://doi.org/10.23919/EMC.1999.10791534

Ziemer, H. (2025, June 11). Illicit innovation: Latin America is not prepared to fight criminal drones. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/illicit-innovation-latin-america-not-prepared-fight-criminal-drones