How the “all against all” theory shaped our understanding of warfare.

:: THE WAR OF THE WORLDS ::

At the end of the 19th century, no one would have believed that this world was being meticulously and carefully observed by intelligences greater than man’s and yet equally mortal; that there was someone studying and analyzing humans engaged in their various activities with almost the same diligence with which a man with a microscope might scrutinize the ephemeral creatures swarming and multiplying in a drop of water. With infinite complacency, humans went to and fro on this planet, absorbed in their activities, confident in their supremacy over matter. Perhaps microorganisms under the microscope do the same.

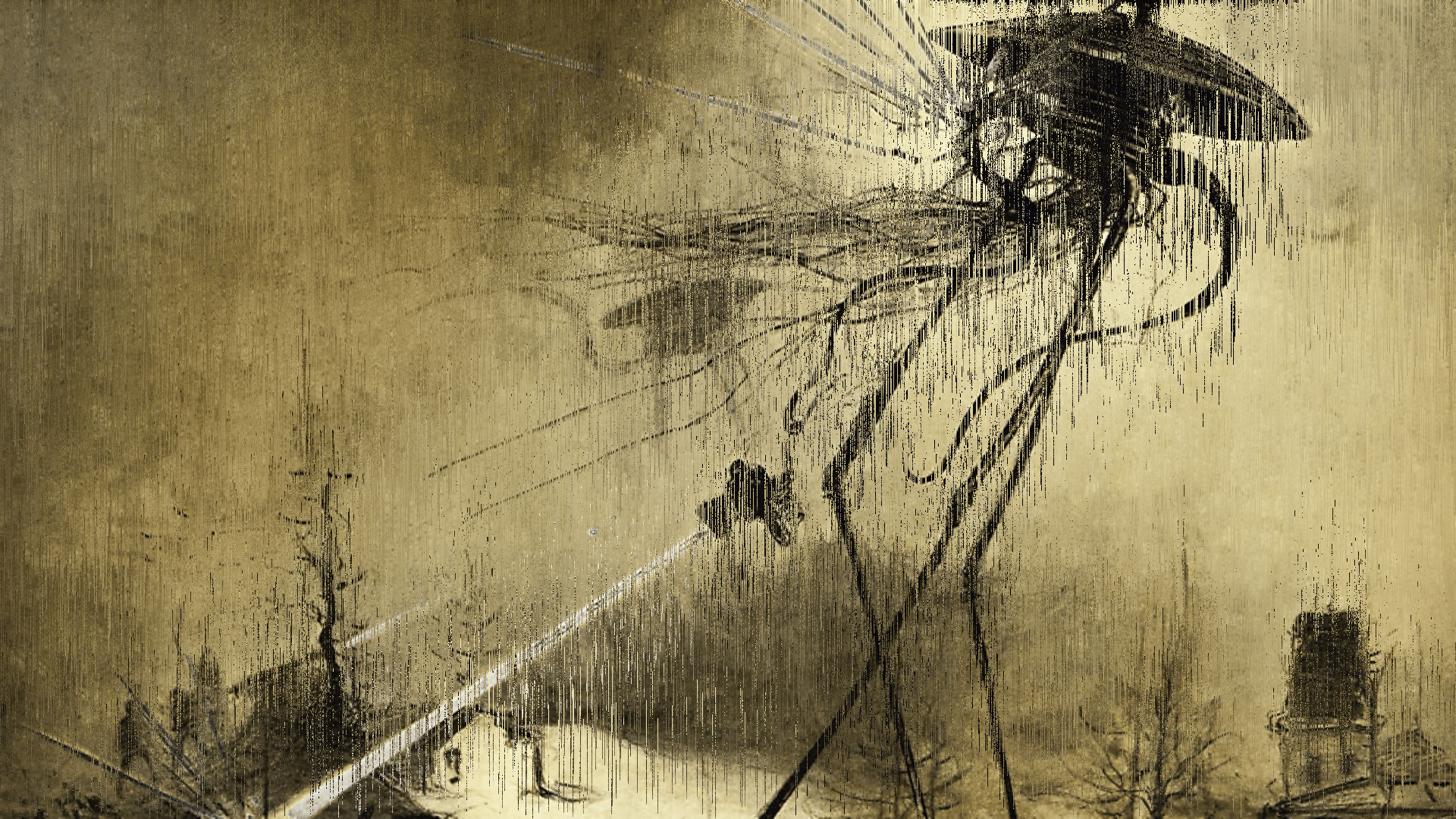

Thus begins one of the greatest masterpieces of modern European science fiction, The War of the Worlds (1898) by H.G. Wells. It is difficult to find a text that more accurately introduces the reader to the pseudo-geological epoch called the Anthropocene. Here, modern humanity, embodied by the British colonial power, finds itself facing an alien invasion by the inhabitants of Mars: a technologically advanced species of giant octopuses plagued by a scarcity of raw materials and energy sources on their home planet. For the first time, Earth is configured as an appealing area for great extractors from other worlds. In this sense, the core concept of the novel is not so much that of otherness or the unknown but rather the Darwinian “struggle of all against all,” the competition between species in a closed and finite cosmic Malthusian ecosystem.

However, two other macro-themes are at the center of the entire narrative: technology and species. The first develops around the comparative analysis of human and alien technologies. At the height of the conflict, we witness the arrival on the battlefield of the most formidable warship of the British fleet, the HMS Thunder Child. The war machine barely has time to showcase its firepower before being immediately destroyed by the heat ray of one of the many Martian tripods. It is at this point that the disparity between the attackers and the defenders becomes entirely apparent. In this context, the vulnerability of the modern human, who is presumed to be “advanced,” manifests through the trauma of an invasion from a non-human Outside.

The second theme examines the concept of “civilization,” presenting the reader with certain human types incapable of surviving a planetary invasion phenomenon. Wells shows how vulnerability and cooperation are the key words within a scenario of extreme asymmetry in warfare. Throughout the novel, human weapons prove entirely insufficient to confront the Martian ones; the same can be said of behavioral strategies such as superstition, selfishness, cowardice, and nihilism—especially when compared to the cold, calculating rationality of the invaders. The pastor and the artilleryman are two characters with strong ethical significance: on one side, the priest-ascetic who sees in the existence of aliens proof of the non-existence of God and ends up plunging into an abyss of meaninglessness and despair; on the other, the Nietzschean “last man” ready to sacrifice the entire species to save his own life.

Wells seems to want to show that it is not the strength and intelligence of the individual (or military apparatuses) that constitute our species’ main advantages, but the ability to connect individuals in a network of significant relationships: cooperation—both interpersonal and intrapersonal. This hypothesis could even be extended to mammals in general, including our most distant ancestors.

It is important to remember that The War of the Worlds stages the Victorian drama of extractive colonialism. The Martians behave in the same way as British invaders: they seize resources, devastate ecosystems, and kill without any remorse. At the heart of the Martian technological apparatus, as well as the colonialist one, is the dehumanization of the other: given the failure to recognize the other as a “living, cognitive, and sensitive being,” technology—no matter how advanced—becomes an instrument of extermination; of governance through control, discipline, and bureaucracy; and of extraction and value enhancement.

It is no coincidence that one of the most disturbing activities of the Martians is the practice of capturing and detaining humans, which could be related to food or energy supply practices, or even both. It is not important to draw a clear distinction between the three, as what really matters is the “sacrificability” of the other and not the ultimate purpose of their death. What difference does it make to a sacrificial victim whether they end up in the digestive system of their killer or their boiler? The basic principle, after all, is exactly the same.

In many ways, the events of the alien invasion are anticipated by almost forty years by those of the Second World War, not only because of the necropolitical paradigm of mass extermination or the tactical paradigm of the “blitzkrieg.” What is called into question is the mobilization of the entire society, all institutions, and all techno-economic devices for war purposes. The Martians do not simply invade and conquer: their goal is the total annihilation of the human species from every point of view. In short, the aliens’ aim is to incorporate the entire planet into Mars’s metabolic processes. It is no surprise, therefore, that Homo Sapiens finds itself having to mobilize every single resource at its disposal—something similar to what happened during the American invasion of Vietnam.

Another extremely relevant aspect is the use by the Martian army of unconventional weapons, the most spectacular of which is undoubtedly the “red weed,” a sort of heather or weed that spreads on the Earth’s surface, suffocating the local flora and contaminating the waters. This use of terraforming allegorically reflects the destruction of indigenous territories by European settlers, but it also anticipates by two hundred years some of the darkest potentials unlocked by the fusion of geoengineering and genetic engineering. Throughout the book, the intersection between the theme of technology and that of life forms is represented by the possibility of interpreting life itself as a type of technology.

Representative in this sense is the ending, in which the seemingly unstoppable Martians are exterminated by the pathogens populating the Earth’s atmosphere. Here, the parallels between technical life and technology culminate in a biologist’s suspension of temporal linearity: everything coexists with everything else since evolutionary processes do not occur in a succession of “before” and “after,” but in a contemporaneity of genetic and phenotypic traits. Hence the competition between species from different eras and ecosystems. Biological simultaneity is the factor that makes the advanced Martian technology completely powerless against two of the oldest and most “primitive” forms of terrestrial life: viruses and bacteria.

The great scales and deep time that frame The War of the Worlds offer us various insights for thinking about climate change and the technological singularity as alien phenomena, by virtue of which the human species finds itself having to deal with an Outside that codes the unknown not as a function of the known (that is, as a “not-yet-known”) but as an “unknown-in-itself.” A dark energy that draws every point of the universe towards a centre that is at once everywhere and nowhere.

: : THE DARK FOREST : :

What might the axioms of cosmic sociology be? First: survival is the primary need of civilization. Second: civilization grows and expands continuously, but the total matter of the universe remains constant.

In The Dark Forest (2008), the second installment of Chinese author Liu Cixin’s sci-fi trilogy, Wallfacer Luo Ji’s magic is entirely based on this assumption that he himself elaborated. Everywhere, scarcity and the search for new resources lead civilizations beyond their natural boundaries. It is the techno-economic development that causes all societies to eventually overflow beyond their original ecosystems. A refinement of the model offered by Wells in The War of the Worlds.

This premise leads to a general theory known in history as the “Dark Forest Theory.” According to this theory, the existence of a dimension of absolute competition and conflict, aggravated by the fog of war afflicting the cosmic battlefield, makes the most economical and rational choice for survival and the transmission of one’s genes and memes to hide. The same paradigm can be observed on a smaller scale within a forest ecosystem, where smaller or more vulnerable animals tend to avoid being perceived by other organisms. In short, it is an eminently wise response to the old Fermi paradox: if the universe is teeming with advanced civilizations, where is everybody?

In doing so, Liu’s epic extends the notion of “war of all against all” on a cosmic scale, presenting the reader with an advanced socio-philosophical theory of camouflage. From this theory also proceeds an interesting corollary: it goes without saying that as soon as a planetary civilization discovers another less developed one, it would try in every way to destroy it to prevent future conflicts.

Like the Martians, the Trisolarans (the “villains” of the saga) had the opportunity to spy on the human species in secret. Unlike their predecessors, however, the asymmetric warfare model used by Trisolaran strategists involves infiltrating terrestrial ranks; a plan that leverages the same human types identified by Wells, namely, the selfish (those hoping to profit from the invasion), the nihilist extinctionists (like Ye Wenjie and Mike Evans), and the deserters (the “escapists” in Liu’s terminology). It is these characters, fascinated or corrupted by the Trisolaran empire, that delay Earth’s reaction times by decades, engaging all involved actors in a global war on terror.

Once again, Homo Sapiens are presented as a vulnerable animal capable of making great evolutionary leaps, provided it preserves a solid social fabric. It is no coincidence that Liu places great emphasis on the communicative abilities of our species: The truly exceptional ability to engage in linguistic games such as storytelling, self-deception, and lying is what makes the human species particularly adept at manipulating the enemy and its own mind, camouflage, and intelligence. The Trisolarans themselves—who communicate through the immediate transmission of thoughts and emotions—require hundreds of years, as well as a period of “distant” cohabitation with humans, to learn how to lie effectively.

Unlike Wells, Liu seems convinced that it is not courage and hope, but rather the awareness of one’s irreducible weakness—and the healthy dose of realism that follows—that configures Homo Sapiens as a valid competitor in the game of the Dark Forest. (Without giving too much away, suffice it to say that in the final chapter of the trilogy, it will be the last remnants of compassion and humanist pity that seal Earth’s ultimate fate).

Luo Ji is the character who most embodies this doctrine of radical asymmetry. A former astronomer and ex-sociologist turned alcoholic; a successful popularizer haunted by the shadow of failure; a solitary man who has made himself his own raison d’être; Luo Ji is forced to confront his demons when the United Nations entrust him with devising and safeguarding humanity’s military strategies. Following an incident that endangers his life and makes him fully grasp the cosmos’s indifference, Luo Ji conceives the Dark Forest theory, from which derives a series of tactics exploiting the cosmic mechanisms of natural selection. Among these, the most spectacular is the use of Trisolaris’s planetary coordinates as a blackmail tool to halt the invasion: in the absence of a diplomatic agreement, the alien planet’s coordinates would be disseminated throughout the universe, leaving it at the mercy of potential aggressors.

It is Luo Ji who assumes the role of the Swordholder, the man tasked with pressing the transmission button at the slightest hint of treachery from the Trisolarans; a position that forces him to live the rest of his life like a Zen monk immersed in meditation. In the book, Luo Ji himself presents this type of warfare as a form of magic: a “frightful action at a distance” capable of striking the enemy without any need for direct interaction.

:: CLAUSEWITZ AND THE ARTILECT WAR ::

In his military strategy manual On War (1832), Prussian General Carl von Clausewitz presents a speculative hypothesis regarding the material limits of warfare. Given the escalation, or the intensification of conflict in response to the enemy’s war efforts (for example, the transition from military invasion to bombardment), it is necessary to consider that the ultimate limit of war consists in the total extermination of the enemy. This outcome simultaneously refutes and verifies the assertion that war is “the continuation of politics by other means.” In opposition to “real war”—dominated by rational objectives and ends—Clausewitz refers to this enigmatic attractor as “absolute war”: the space where politics yields to war-in-itself, or where ends coincide with means.

According to Clausewitz, absolute war is the true purpose of war in itself and for itself, as an abstract entity: a purpose that humans bend to their own ends, from diplomacy, plundering, and the desire for expansion. In a sense, it is as if Homo Sapiens accesses, every time it initiates a conflict, the field of absolute war and attempts, in every way, to take the reins of a beast roaring beyond time and space. A transcendent bond that one seeks to reduce by curbing escalation, which is the natural order of war, and limiting the duration of the clash as much as possible. Diplomacy, for Clausewitz, is the only tool available to the species to demonstrate to the adversary that the continuation of conflict would lead to the total destruction of the weaker party.

This is likely why Clausewitz opposed the emerging paradigm of “total war”—later known as “total mobilization”—in which every single institution, every single organism of the state, from individuals to commercial companies, from schools to newspapers, participates actively in the conflict. The involvement of the civilian apparatus in military operations, in fact, would deprive the state of any element of friction—of “innocent victims,” so to speak—paving the way for hatred towards the rival and, consequently, its physical elimination.

Since World War I, Clausewitz’s speculative hypothesis has been constantly tested, first with global experiments in total war (with the invention of propaganda, toxic gases, aerial bombing, and extermination camps); then, with the emergence of guerrilla warfare and terrorism (in which there is no longer any distinction between military and civilian); and finally, with the establishment of the hybrid model of “unrestricted warfare” (whereby economy and technology become the central elements of warfare).

In 2013, philosopher Nick Land, in his brief essay “Philosophy of War,” suggested that absolute war itself is subject to camouflage, a dynamic, historical vision that projects warfare within a complex but linear process. Taking Clausewitz’s indications seriously, Land plays with the idea that camouflage, the art of mimicry and concealment, belongs to war itself. Based on the military potential developed by the human species over the last hundred years—with the discovery of nuclear weapons and the introduction of new digital technologies—Land asserts that there is no longer any limit to the degree of destruction that can be brought about. A tendency line that, once fueled by escalation, would no longer culminate in the physical annihilation of a given enemy but in the definitive extinction of our species. The point where nothing remains but war-in-itself, a slumbering dragon, waiting for some unfortunate soul to disturb its sleep.

For Land, this would be the secret that war harbors within itself: its ability to manipulate intelligent species; to persuade them to devise and create ever more powerful weapons; its feverish desire to have some unfortunate bureaucrat push the button.

Already in 2005, Australian researcher Hugo de Garis, who had moved to China to collaborate with Wuhan University, posed the fundamental question of how artificial intelligence intersects with military practices.

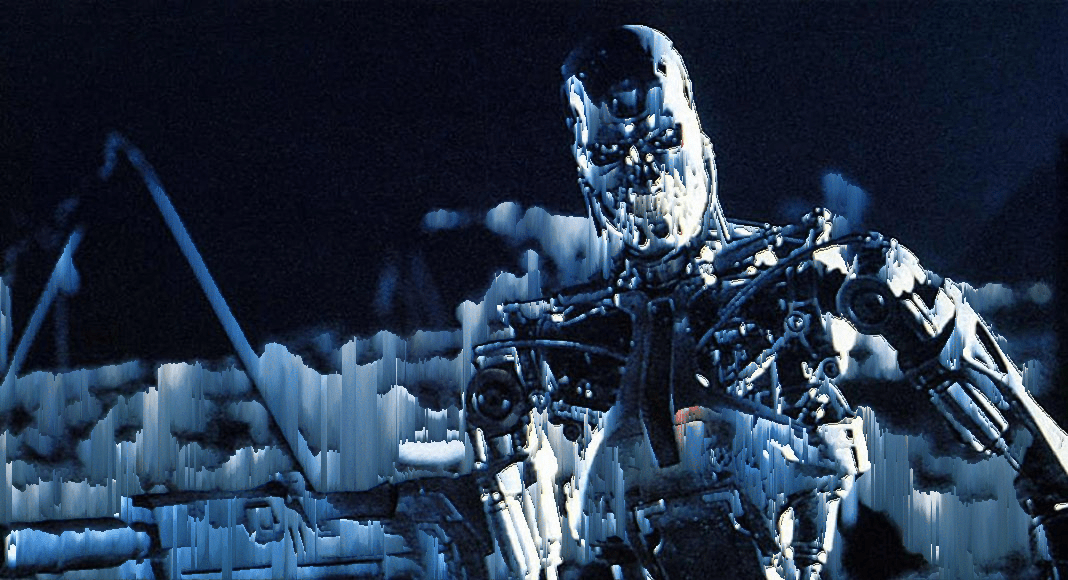

In de Garis’s vision, humanity’s future is dominated by the common but competitive effort to create true artificial intelligence: AGI (Artificial General Intelligence). To this end, all the world’s states will mobilise their scientists, diverting substantial sums of money into engineering and computer science projects; all corporations in the sector will focus on developing increasingly efficient learning models and producing increasingly powerful and cheaper components.

This development model, for de Garis, is the same as military escalation: First, the first state or company to invade the market with its patented technology will push all others to do the same and raise the stakes. Second, this shared goal will lead to increasingly advanced machines until the creation of the first Artificial Intellect: the Artilect, in de Garis’s jargon.

But there is another aspect that the artificial intelligence sector shares with that of war: the tendency to polarise public debate. In his The Artilect War (2005), de Garis envisions a nightmare scenario for humanity, one in which defenders of biological intelligence oppose the creation of the first Artificial Intellects by all means. Initially, a few academic articles here and there, a proliferation of control bodies, and rambling preachers of a new impending Apocalypse. Later, with the loss of the first jobs, the automation of production processes, the delegation of various decision-making processes to algorithms, and the return to an updated form of Luddism, a vague sense of threat hovered over human civilization like a toxic cloud. Finally, the founding of political parties and militant groups opposing the allocation of funds to AI projects, strikes, protests, acts of sabotage, and terrorist attacks on laboratories and production facilities.

Cosmists against Terrans, proponents of unlimited techno-economic development against staunch defenders of the ontological and moral status of human beings. A constant and progressive state of emergency, where the enemy is the species itself, feeling threatened by the rapid changes in global structures and opposing state interests. For de Garis, it is precisely in such a context that Artilects would be used not to benefit Homo Sapiens in administrative duties, work, and leisure, but to quell and extinguish revolts, annihilate opposition, and eliminate any obstacles definitively. An eventuality that, at the time, seemed inspired by the most visionary science fiction but is now not so hard to imagine.

War in the hands of a machine: a network of interconnected devices managed by an intelligent, impersonal entity, endowed with a computational capacity far superior to that of humans. A weapon that takes possession of war or, perhaps, as Land would put it, war-in-itself incarnated in a machinic avatar. This is the purpose of camouflage: to disguise the course of one’s attack strategy through an increasingly complex and refined series of disguises.

Here, in the jaws of the most advanced hyper-modernity, the primitive is still represented by the competition of all against all: a paradigm suggesting (following Liu and Wells) that the strongest must seize all resources and prevent any potential interference from other organisms at any cost. This is what we humans do, after all, despite having long since tamed all other forms of life: nature reserves, domestication, and controlled breeding programs for large predators.

The extinction of the human race at the hands of machines is the culminating event through which the primitive floods into hyper-modernity, submerging and replacing it.

:: SPECULATIVE PROCEDURES ::

In the end, the paradigms proposed by Wells, Liu, de Garis, and Land need to be compared with the current state of affairs. In all the authors mentioned, the danger seems to come from a speculative Outside of partially or entirely transcendent nature: the extraterrestrial, the hidden god, and the intelligent machine. Each of these narratives offers, as a guide, an attitude of cautious mistrust, a preventive pessimism that contrasts with the naive enthusiasm of those astronomers who send encrypted messages drifting into open space.

But how much of this can prove useful in the context of an operational program aimed at exploring and managing the unknown?

At this moment, the main existential risks that humanity faces are essentially three. In order of relevance and imminence, they are global warming and the associated climate change, the abandonment of the unrestricted warfare model and the eruption of a high-intensity conflict on the international stage, and the technological singularity and the disintegration of the social fabric.

In the first case, focused on climate change, we know for certain that we have exceeded the planet’s extractive capacity. Additionally, we know we cannot avoid temperature increases or extreme weather events; we cannot predict the extent and scale of positive feedback mechanisms; and finally, we lack the tools to mitigate the economic, social, and ecological consequences of global warming. We find ourselves stuck in a condition where an invisible, yet omnipresent enemy strikes us from a fog of war accumulating around the planet. This is the clause identified in 1651 by the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, for whom the only authority capable of toppling the absolute power of the Leviathan would be God himself, under the guise of natural disaster or adverse fate.

Here, Wells and Liu suggest an intervention model based on cooperation between individuals, institutions, and states, aimed at emission mitigation and reduced production and consumption. Otherwise, if we tacitly decide to watch the world burn, the results would not be much different from what de Garis envisioned: protests, riots, mass migrations, terrorist attacks, overpopulation, and military operations aimed both at seizing water and food resources and at containing migratory flows. The only solution would be to equate global warming with an alien invasion: a cosmic-level threat that involves all of humanity without distinction.

In the second and third scenarios, the appearance of an absolute warfield could lead to an unprecedented escalation. The cross-use of nuclear and biological weapons, new technologies, industrial espionage, media, and sanctions, already spread out by current world superpowers, does not just raise the question of how future wars will be fought but offers an intensive picture of it: from post-truth to total illusion; from disparities in information distribution to their total interdiction; from subsistence economy to mass death. Not coincidentally, in his “The Artilect War,” de Garis hypothesizes an increase in destructive power from Megadeath (the indiscriminate killing of millions of people) to Gigadeath (the indiscriminate killing of billions of people), made possible by the development of predictive models and operational protocols impossible for a common human being to follow.

While AGI, for now, remains a mirage, it is not out of the question that in the coming years, we could achieve a level of efficiency and precision that fully simulates human intellect—along with unprecedented speed and computing power. From this point of view, Liu and Land propose the most interesting approach to risk management. At the conclusion of his article, Land states that “we can only think about the way things hide” and that “thoughtlessnes loses wars.” We should take him literally since, assuming the plausibility of the Dark Forest Theory, one immediately realizes that the project to create an Artificial Intelligence resolves into a gamble in which the survival of the human species is at stake. Here too, the appearance of the enemy on the event horizon can be likened to the first signs of an alien invasion; with the crucial difference that it is us who evoke the demon from the Outside, and we can reasonably predict its evolution.

It is biology, not ethics or morality, that suggests abandoning the project of creating Artificial Intelligences to directly focus on the radical enhancement of the natural faculties of Homo Sapiens. An objective that would allow us to challenge the limits imposed by evolution on scientific analysis and space travel. In the latter case, we might even encounter new solutions suitable for addressing the problems posed by global warming and the depletion of fossil fuels. Rather than weakening the human spirit, the idea of an eternal and inescapable war of all against all can help fuel a horizon that is both utopian and pessimistic, where—as Carl Schmitt put it— “Spaceship Earth” projects itself towards the playful and cooperative exploration of the unknown universe.