“Truly [I say] to you, Judas, those who offer sacrifices to Saklas […] everything that’s evil. But you’ll do more than all of them, because you’ll sacrifice the human who bears me. Your horn has already been raised, your anger has been kindled, your star has ascended, and your heart has [strayed].” Author(s) Unknown, The Gospel of Judas based on the Coptic manuscript of Codex Tchacos 3.

“How can we speak of the ex-human, the human that is no more – or, perhaps, the human from whom we are or will be divorced? ”

–Michael Bérubé, Introduction: Learning to Die, The Ex-Human.

—————————————————————————-

Learning how to better betray your own species—specifically, Homo sapiens sapiens—becomes a treacherous endeavor in itself.

We live in an age where digital cult followings have formed around immensely wealthy and powerful individuals who seem to view themselves not just as untouchable demigods, but as self-appointed seers of existential risks and protectors of future, unborn generations. At no other point in history have we been able to think of ourselves as a unitary species, or even dream of speculating and calculating what our survival rate as an entire species might be during immense expanses of unknown future epochs, even as we wander across Big Filter probabilities that, for all practical reasons, we should, by now, fully understand.

Yet, for a species with such a faulty capacity to think volumetrically on a large scale, it is natural that our minds are unable to grasp the aggregate volume of our species at any given moment. It follows that in the future it will become even harder to imagine the total volume of the human population in metric tons (which is over 390 million metric tons).

According to this recent mind-boggling calculation, we as a species outweigh the total biomass of all other animals (except domesticated animals), with the total weight of all humans alive today being six times that of all wild animals on the planet combined. In light of such crushing proof, it appears that we are just not cut out to be good betrayers to our species as a whole, although there is ample evidence we have been very treacherous throughout history, and still are, toward certain groups, classes, and subdivisions of humankind.

To separate mere individual treacherous acts from larger, planned, or at least more convoluted forms of species betrayal, we need to first spell out more mundane examples that everyone should be aware of. So, there is the daily betrayal of every push notification, every song played, every post, text, stream, FaceTime call, Zoom meeting, and every instance of doom-scrolling. The cumulative effect and impact of all these actions intensify and continue fanning the flames of the planetary funeral pyre. Deep down we all know this, and we participate in it with a certain frisson and ardor that belies such day-to-day automatism and general passivity.

One way to evaluate or make sense of betrayal in the midst of so much catastrophic voluntarism is to approach it from the perspective of the history of religions, of philosophy and human sciences. One could follow the rise of Christofascism, for example, or even consider that instead of The Morning of the Magicians, we were left with a more sinister sacrificial pit in The New Paganism: ‘How the Postmodern Became the Premodern,’ as Timothy Snyder argues in one of his recent online lectures.

It is hard to argue against the ample evidence that we are extending earthbound imperialist and extractivist fantasies and rivalries, fueled by militaristic, religious, and corporate interests, into the furthest reaches of outer space. This is the starting point of Mary-Jane Rubenstein’s recent book Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race. It is also the main presupposition behind the most recent addition to the Alien franchise, Romulus (directed by Fede Álvarez).

Any attempt to ameliorate the betrayal capacity of the human species should also consider the idea that today, even the most innocuous, desperate, and symbolic gestures risk being easily outlawed or labeled as ‘eco-terrorist‘ acts carried out by foolish apostates who dare to expose the ongoing death cult of highways, secretly polluting VW defeat devices, and car industry lobbies.

In this sense, becoming a better traitor to your species does not involve treasonous activities such as driving more diesel cars or ordering another pair of Trump-branded sneakers on Amazon. Even if these are simple and apparently effective acts that are hard to ignore or negate, I assume a deeper level of inter-species complicity, and particularly one that involves becoming a willing agent of dispersal, advocating for the extinction and banishment of your own kind from the Earth.

And I am not referring here to the Wormwood לענה (la’anah), even though that botanical emblem of end-times, self-immolation, and Chernobyl-like environmental pollution from a falling star speaks louder than thousands of words about earthly bitterness spread far and wide. It is nearly impossible to persevere and be an egalitarian in matters of species betrayal, without falling back on daily habits of impotent and misguided misanthropy.

Perhaps most frustratingly, we turn out to be only half-willing enablers and traitors to our species, even though we show a propensity to betray countless non-human species at every turn. Because of this, the delicate question posed at the beginning of this text might require multiple, more nuanced answers—answers that I, for one, cannot promise will satisfy every future traitor to the human species. Please consider this a stub to a possible manual or booklet that will bring together disjointed ‘species betrayal’ cases, drawn almost randomly from natural horror movies, books, comics, and other media—all the heinous pop and trash detritus that continues to inform my artistic practice. Over the years, this has resulted in a series of rare public horror(work)shops entitled Swarmer Frotteurism and Post-Invasive Hyperdensity.

These are ways to go against our better instincts and attune us to hellscapes that we would normally ignore or avoid. This way, we can actively search for places we not only reserve for other species (think battery cages or monoculture fields), but also actively converge with dangerous moments and situations we are normally not drawn to. Think of the rush hour squeeze, public transport at maximum occupancy, and agglomerated beaches. One might say Swarmer Frotteurism acts as an antidote, bringing you closer to what the liberal Western subject innermost fears—anxiety and dismissal of the masses and the power of crowds, usually portrayed either as hypnotically blinkered or as blinking like coordinated pixels, hard to distinguish from the swarming, inchoate masses of the non-human other.

Swarmerist Frotteurism counters not just the segregationist individualism that has bred so many gated selves, but also recognizes the way such repulsion from the majority and praise of separatism exist in a species that, throughout its evolutionary history, has rarely encountered large numbers of its own kind. The feeling of being a small part of the largely unseen and unknown vast majorities of one’s own species is something that most people in the West experience only when they leave their own country or visit the few megacities of the Global North. Let us remember what it was like for traders and visitors from low-density societies to visit million-strong ‘hyperdense’ cities a thousand years ago.

Such fears of being swamped, contaminated, ‘invaded,’ or penetrated by multiple others appear to underlie much of the toxic ‘white fear‘ literature of the early 20th century, which informs much of the anti-immigration discourse today. Conversely, there is ample room for delineating the gregarious and erotic potential of swarmerism—perhaps along the lines of what Olivia Wilk called ‘Erotic of Rot‘ in an essential essay written during the COVID lockdown period.

A hivemindful Naturphilosophie must take into account both ever-larger wholes and looming compossible particulars, leaning less toward Hobbesian and more toward Leibnizian Leviathanism. It must address both the necessity and exaggeration of incompressible agglomerations, as well as the fearful and lustful, fluctuating, and cyclically reappearing hyper-densities. It must also include hiveminding, experienced and conceptualized as imperfect states of disturbingly intimate and excessive xtro-body melt.

Mediating between such extremes, a hivemindful Naturphilosophie must develop a sense for ‘a disturbance in the Force,’ attuned to dreadful cosmic silences, accumulated feelings of impending loss, and potential Last Contact Omega messages—topics I tentatively explored in my essay collection Cosmic Drift & Temporal Divergence. In this sense, it must also account for the missing, extinct multitudes that stopped signaling long ago.

Swarm-diving and post-invasive frotteurism can be considered the uneasy, completely ignored, and maligned side of ‘Swarm Intelligence’ studies, as narrowly defined in the description of the ‘intelligent’ (or sapient) behavior of Cellular Robotic Systems in a 1989 paper by Gerardo Beni and Jing Wang. What was cheerfully greeted as ‘The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World‘ in the early 1990s turned out to be just another phase in the total subsumption under capitalism and a preparatory stage for Big Tech consolidation.

If one scratches the surface of the ‘neo-biological world’ hailed by the tech gurus of bygone days, one might encounter a darker, more vitalistic, yet unspoken undertone. One might also uncover how this eager embrace of swarm intelligence and self-organization under the invisible hand of Venture Capital continued the same game of theoretical and geopolitical strategies that came to define ‘containment’ during the Cold War. The night side of swarmerism carries with it a vaguely anti-humanist, quasi-ex-humanist ballast, looking back at what it meant to be human—everything scraped away by the full decentralization of technolibertarians. We might find a Pandora’s Box of ecological horrors, including nature-run-amok horror movies: The Birds, The Bees, Long Weekend, Phase IV, The Empire of the Ants, Slugs, Habitat, Mimic, Bug.

Post-Invasive Hyperdensity was meant to explore higher states of today’s density and to counter the desire to separate from the masses or look away from natural phenomena like Zebra clams living in stacked layers or processionary moth caterpillars moving in a robotic lockstep to deter predators. Following or freeing migratory locusts might also have unexpected and broader impacts. In 2014, as a contribution to the Utopiana artist residency in Switzerland, Geneva, we organized the first ‘Swarmerism horroshop’—inviting participants to decide whether to release several female migratory locusts (Locusta migratoria) from a local pet shop into the surrounding gardens. In retrospect, this might be considered an apt retribution for the way life seemed to go on undisturbed, with everyone tending their own little private patch of garden and Zone of Interests, even as the community gardens and the residency itself had to give way to an urban redevelopment project, forcing a move to another location.

If Switzerland, the paradise of the über-rich, where one in seven citizens is a millionaire, is a country with a political tradition of direct democracy, we could hypothesize that the Swiss might also vote on specific issues such as releasing a so-called swarmer polyphenic transitional non-migratory form. Both forms have rarely been seen north of the Alps. This was, of course, not so much a discussion about native versus non-native species or biodiversity loss, but rather about the role of intentionality and the orchestration of intentional super-spreader events at a time when deciding on humanity’s shared future—or lack thereof—seems impossibly remote.

Suffice to say, it was a tough and controversial decision. However, it was important to highlight the participatory aspect—willingly acting as traitors to their own species—by allowing them to reintroduce the migratory locust, rather than simply hosting the Swiss Centre for Locusts and Migratory Pests. This was not done for biblical ‘plague’ reasons—although one cannot deny that might still be a factor for some—but rather for rewilding purposes and to recognize what is already happening sporadically. Locusts were much more common in Europe in the past, and Europe is now suffering from an ‘insect apocalypse’—a steady decline in insect numbers due to changing weather patterns.

Although the Utopiana vote was against releasing the locusts, as is often the case with backdoor dealings and favoritism, the migratory locusts still got their chance. It must also be emphasized that, at the time, Japanese knotweed was being combated along the shores of Lake Geneva, right next to the Botanical Gardens. Focusing on such treasonous relations and searching for an acolyte of species betrayal heightens one’s attention and ability to make a conjecture about the future of other unintentional species releases. Even though the surrounding gardens still looked manicured, there were worrying signs that not everything was going according to plan.

The planting stock of Buxus sempervirens managed to carry the Cydalima perspectalis (box tree moth) into many places around the world. The moth has since been munching away at our box tree geometric gardens and green enclosures. As we are undoubtedly responsible—some of us more than others—for the rapid disappearance of megafauna in the past, and for the ongoing loss of countless lesser-known species today, one might become more focused and preoccupied with becoming a willing agent of human species decommissioning. In conclusion, and even in regard to the locust, our entanglement with species dispersal and species treachery is never straightforward.

Interpreting and reading locust swarms is often a hazy affair. We cannot be sure who is actually benefiting, nor if our betrayal ultimately benefits the human species—especially given our poor ability to differentiate between short-term and long-term gains. I think we can generally agree with Jeffrey Lockwood’s assessment of the Rocky Mountain locusts: while their swarms temporarily spelled destruction, they also added vital nutrients and constituted an unexpected boon for local agriculture.

In 2017, three years after our migratory locust release party at the Utopiana swarmerist horroshop, came an unexpected development: the new Foodstuffs Act. Swiss supermarket giants Coop and Migros began developing insect-based dishes after the government approved mealworms, crickets, and locust-based foods.

While the new insect boon might be appealing for some, it also constitutes prime fodder for disinformation campaigns. It has been co-opted by right-wing, anti-Semitic, and racist online conspiracies, as well as 4chan memes. I won’t go into detail here, but one can easily dip into the ‘EU forces its citizens to eat insects’ conspiracy maelstrom. Simply put, whenever insects are mentioned, it reveals how widespread their dystopian vilification has become, as they are often perceived as threats to both humanity and ‘our way of life.’

La Nuée—which translates to The Swarm—is a 2020 French horror drama directed by Just Philippot, based on a screenplay by Jérôme Genevray and Franck Victor. It’s not a particularly good horror film, but with its single mom unsuccessfully trying to raise her kids by selling locusts as protein, the movie taps into Europe’s fears about how the new protein transition has entered the consciousness of its meat-based food chains. In the film, the farmed locusts themselves appear to have abandoned their herbivorous diet and developed a taste for human blood.

Like an inversion of Renfield, the manic and deranged servant in Dracula, Virginie, the desperate French insect farmer, begins feeding the locusts with her own blood. This recalls the story of the great Buddhist master Asanga, who, in an act of compassion, fed maggots on a wounded dog with his own flesh.

Whenever we speak of entanglement or interdependence, we usually do not mean working together to the disadvantage of one’s own species. In the end, it might be difficult to follow such complex causal chains or clearly determine who or what ultimately benefits from these species betrayals. However, in order to widen and refine our scope, we must learn from many banished others. These banished others of biology have been generally declared species non grata—the so-called neophyta or neozoa—‘invasive’ or introduced species that harm their new environments.

Like many such abuses of biological metaphors used outside their context, biological fallacies are instrumental in fomenting racist fears and feed on deep-seated anxieties about newcomers, oddities, strangers, and the unfamiliar—about what tries to distinguish the natural from the unnatural or supernatural. When the word ‘invasive’ is used, it becomes part of the hate-mongering arsenal of ethno-populist propaganda, dehumanizing targeted groups of migrants and refugees. This is done by directly associating them with teeming, swarming, and dangerous ‘foreign’ species. We must combat such associations from the start, especially because they hold high currency in today’s right-wing xenophobic climate.

That said, we must recognize how so-called green biocapitalists, with their promises of renewable capitalist prosperity, have delivered something entirely different—and far more bitter. I’m referring to certain political species that have been trafficked along trading routes and imperial global networks, often because they resembled more economically valuable ones.

We must learn a hard lesson from all those innocuous gardening and ornamental escapees that lure us with their lavish inflorescences and drought- or pollution-resistant abilities. We must grasp the final irony of Imperial Ecology’s living nightmares: homesick, cultured settler colonialists and acclimatisation societies that released species from the works of Shakespeare into new environments, wreaking havoc.

We must also confront the uncomfortable truths of agribusiness’s non-human survivalists and pet shop renegades—species that have learned to thrive beyond their allotted grounds, greenhouses, or balcony pots. Despite biosafety regulations and millions spent to eradicate them—not to mention the New Wallace Lines—these species demonstrate how easily they can hide within an unlucky bamboo plant and cross continents. Thankfully, we don’t need to fathom all these dispersal moments, as countless fictional arthropod species provide tutorials in species-wide betrayal.

One such curious example is the fire-producing, eponymous Hephaestus parmiter bugs from the 1973 science fiction horror book The Hephaestus Plague. The book was later adapted into an American horror film directed by Jeannot Szwarc and written by William Castle and Thomas Page, the book’s author. Professor James Parmiter, who named these fiery bugs, might easily be seen as the typical mad professor trope of science fiction. However, he is better described not as mad, but as a conscientious objector to human survival or an unlikely anti-speciesist traitor.

In fact, while Parmiter may seem to play the opposite role of Dr. Nils Hellstrom from The Hellstrom Chronicle—a seminal sci-fi horror film mixed with documentary shots—he is quite similar. Like Hellstrom, an early critic of liberal subjectivity and excessive individualism, Parmiter ultimately fills the same difficult role: an apt betrayer of the human species, announcing its incapacity to act collectively as a social animal.

As historian of ideas Thomas Moynihan investigated in a recent article on our fascination with insect ‘civilizations’ and bug societies, recasting our place in the universe, Dr. Hellstrom seems to follow in the footsteps of celebrated astronomer Harlow Shapley. In conclusion, humanity is as fallible a research subject as one can find, especially when it comes to its capacity for hive-mindedfullness.

Ultimately, entomology seems to offer much better prospects for finding an inheritor of the Earth. After the brief but impactful reign of the solipsistic great apes at the pinnacle of the Age of Mammals, insects may well be the next in line. Extraordinary species like butterflies, locusts, wasps, termites, ants, and mayflies demonstrate just how flimsy humans are as stewards of the Earth.

Becoming a betrayer to your own species often involves a period of seclusion from your kind, a labour of lonely experimentation and unethical bio-hacking. Returning to Professor James Parmiter from the 1975 movie Bug, we see that the bugs themselves are not as autonomous as they initially appear. Liberated from the depths of the Earth by an earthquake, this obnoxious species of previously unknown pyromaniac insects can create fire simply by rubbing their legs together.

This means they can crawl inside cars, scurrying down exhaust pipes, and cause internal combustion engines to do what they do best: explode and burn their drivers alive. However, these extremophile bugs are, quite literally, out of their depth. Not easily adaptable to above-ground conditions, once they leave their high-pressure lair, they are exposed to what seems like spontaneous combustion.

Suddenly, these little fire-starters depend on their human accomplice, the good Professor Parmiter, who not only makes them more amenable to surface life but also gives their swarm intelligence a boost through his laboratory experiments. In the end, Professor Parmiter is able to communicate with the bugs in one incredible scene, where the Hephaestus insects congregate and use their bodies to form writing on the wall—literally using their hive-mindedness to collectively spell out and signal their newfound self-consciousness. They are now ready to set the world on fire—with purpose.

Another example to quell our specious appetite for enlightened treason is the early 2000s manga Bio Meat: Nectar, a remarkable 12-volume work by Fujisawa Yuki. BM—short for Bio Meat—are man-made creatures. They are not the random product of blind evolutionary forces. They are not some unknown species previously undiscovered by science, but the result of an accidental cataclysmic release into the urban environment. Like in the real life Fukushima nuclear accident, BMs escape their dome habitat through the cracks caused by an earthquake.

They are not the ill-fated result of capitalistic greed or intrusion into the farthest regions of the Earth. Instead, they are a pure product of science—a lab orphan searching for a new home and a new menu. Rather than serving as accomplices to a species traitor, they become instruments of destruction in what could be described as a dialectical insectoid reversal. Outside the confines of metal and glass, these creatures are true junk eaters, designed to solve Japan’s future trash and recycling crisis.

The premise of the Bio Meat manga is circular: why not invent something that could solve our increasingly dire waste problem by developing an appetite for it? Bio Meat is kept under a protective dome, feasting on all of humanity’s waste products, before being slaughtered and sold as food for humans.

They are perfect recycling organisms but, unbeknownst to their creators, also represent a rebellion against scientific progress. Their ultimate betrayal—and higher reason—is to evolve from helpers of the human species into hackers of the food web and trophic levels.

Soylent Green is made out of people, but what it lacks is agency—it cannot escape its chains of production and circulation. In spite of bio-safety measures, it’s difficult for the Japanese government to plan for every contingency. When the Bio Meat species escape, they begin eating through everything in their path, including hapless humans.

At this point, it’s important to understand that many invasive species are actually escapees from global horticultural, ornamental, bio-pharmaceutical, or bio-capital supply chains. These species are introduced because they are attractive in some way—whether economically, aesthetically, or simply to solve a previous problem. They may also trigger a nostalgic response from humans, as is often the case with species brought over as samples of flora or fauna from home.

Meanwhile, these previously tame—or formerly benign—species (with all the anthropocentric and moralistic caveats that such a valuation entails) undergo a sort of Mogwai/Gremlins transformation, becoming agents of destruction.

For those familiar with Joe Dante’s 1984 horror-comedy Gremlins, this story might sound familiar, as humans cannot and do not abide by the rules. The lesson of the Gremlins fable is that something as cute as the docile Mogwai ‘Gizmo’ can easily show its fangs. While the film contains easily recognizable racist and orientalist connotations, there’s something peculiar about what happens when pets escape their petting zoo.

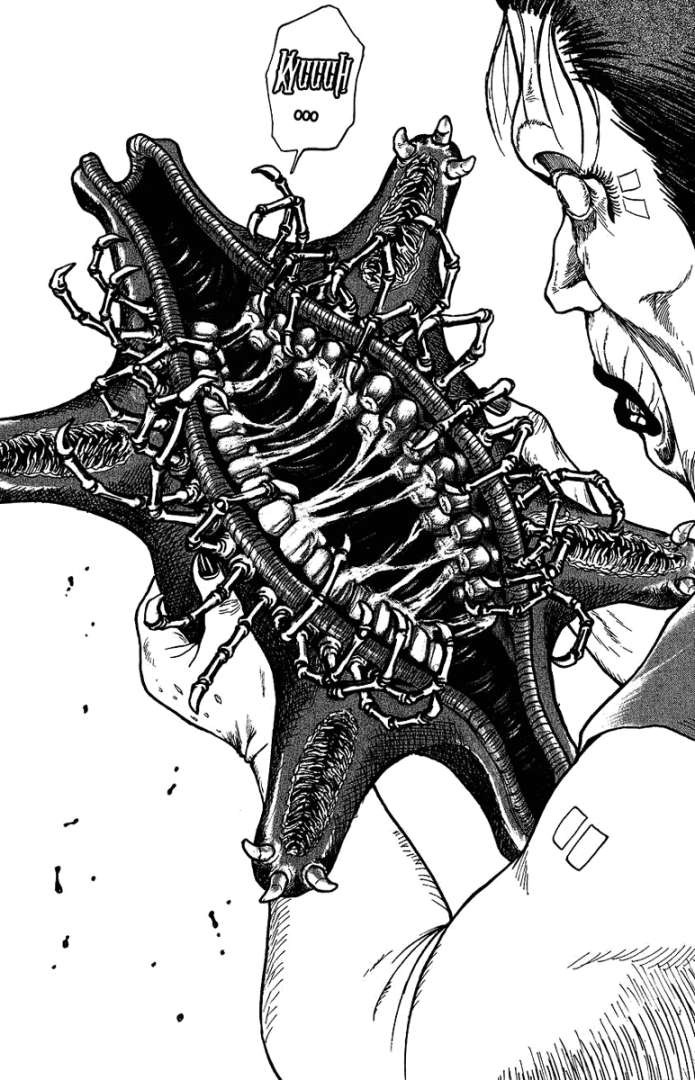

Beyond the oriental curio shop, Clive Barker’s Hellraiser also features a memorable gross-out scene in a pet shop where insects, usually reserved for feeding pets, crawl freely. Similarly, the endlessly self-replicating and insatiable Bio Meat creatures that escape into the streets of Tokyo have a peculiar anatomy. Though not especially gruesome at first glance—resembling small black turtles—they are essentially hellish crawling mouths. Their appendages scoop up food into a central mouth on their underside. They are lab-escaped, crawling vagina dentata.

The Bio Meat creatures also resemble starfish. Based on our understanding of star-shaped echinoderms, one could see them as disembodied heads walking along the sea floor, using their multiple tiny ‘lips’—sensory tube feet—of which there are two rows on each of their five arms. Insatiable, all-consuming humanity has met its match in a humble star-shaped creature that refuses nothing, treating all waste as precious food.

In contrast to major SF theoreticians from the English-speaking world, such as Darko Suvin and Frederic Jameson, the French philosopher Guy Lardreau concluded in his 1988 work Fictions philosophiques et science-fiction that SF is closer to anti-utopianism than utopianism. On the one hand, anti-utopianism is often seen as just a version of ‘There Is No Alternative’ (TINA), promoting a disempowering doomerism that helps justify more extreme shock therapy measures.

Countering this, and picking up where Lardreau left off, Steven Shaviro makes anti-utopianism a preferred mode of SF, one that opens up conjectures without ever fully settling them. Here, we must also consider conjectures about optimization processes, Bio Meat technological solutions, and other feats of capitalist technological prowess.

In fact, the way current SF blockbusters tend to vary and recycle their original formulas suggests they are dealing in ‘bad novums,’ to use Suvin’s evolving terminology, ultimately producing more of the same.

The search for the peculiar, gooey, and oily speculative substances that are abound in the Alien franchise seems to mirror the trickle from the exhausted combustion engines of modernity. These substances also emerge from extractive industries that scan for life-signs of abiotic xenogenesis, seeking to yoke them to corporate bottom lines.

The protean bio-capitalist, mutagenic dream exists to confer that elusive competitive edge to corporations that have already extended into space. If not building better worlds, they are at least creating more xeno-resilient and extremophilic workers.

Compared to the will-to-power of their CEOs and their shipminds‘ prime directives (priority one: ensure the return of the organism for analysis), the biohazardous mutagenic substances wreaking havoc on board seem minor and containable, almost like trivial soda pop substances.

The substance colloquially known as ‘black liquid’ (Chemical A0-3959X.91-15, ‘Prometheus Fire,’ or Weyland-Yutani Compound Z-01 in later Alien films) makes ‘forever chemicals’ seem benign by comparison.

The question of humanity’s role in its own suffering and exploitation is offloaded onto artificial beings, such as synthetics like Science Officer Rook, who conducts experiments with chestbursters and xenomorphs under the guise of improving human life expectancy in space. Of course, this is utter corporate bollocks, as Rook appears more focused on painfully decommissioning humanity.

In the end, focusing on just one change, one act of betrayal, or one substance overlooks the complex web of causes and the larger, often unexpected, shifts and challenges that can emerge from the intricacies of species betrayal.