Tobacco, coffee, alcohol, hashish, prussic acid, strychnine, are nothing but low-grade illusions. The worst poison is time. — Ralph Waldo Emerson

:: :: Dilating Time :: ::

There is no cosmic and existential question that has had a greater impact on human history than that concerning the freedom of our thoughts, choices, and actions. The classic opposition between freedom and necessity runs through all philosophical and theological thought from antiquity to the present day, finding precisely in contemporary times one of its periods of greatest ferment.

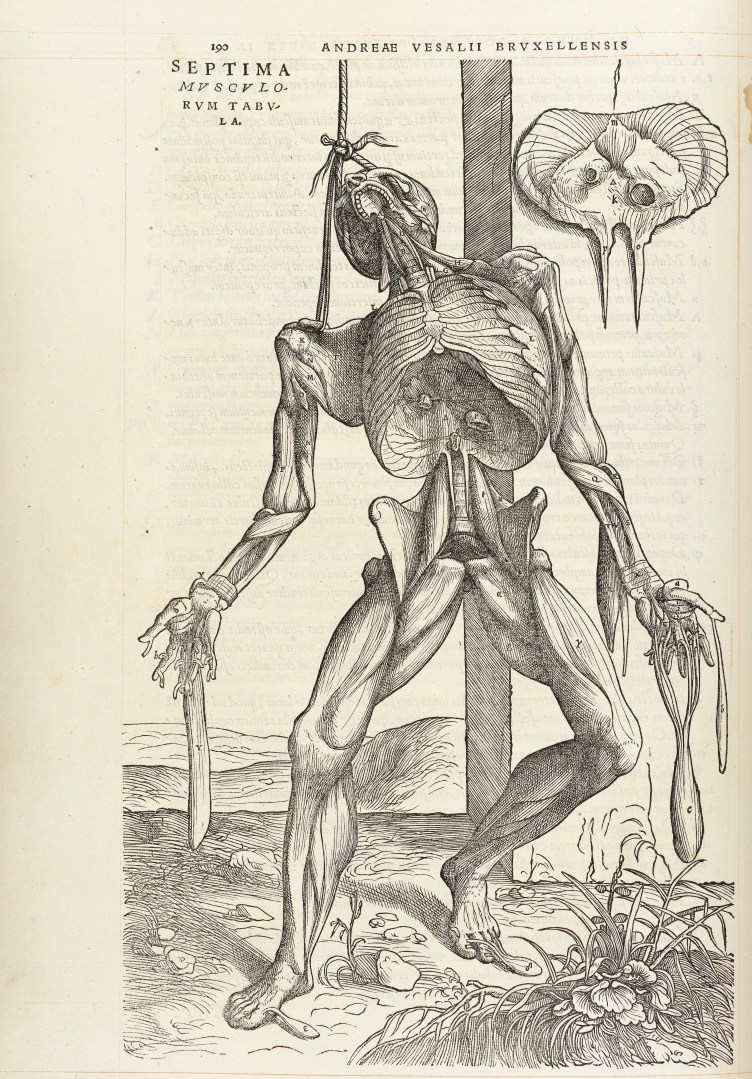

Neurology – with the help of its handmaiden, neurophilosophy – has made determinism its warhorse, establishing that all human behavior is determined from within by brain activity. This, in effect, would imply not only the identity of brain, ego, and consciousness but also the nonexistence of the latter two. This stems from the implicit assumption that an arm or a stomach, in order to function at full capacity, has no need to be self-aware of its own internal perceptions, while an organism’s survival in the environment is definitely facilitated by the possibility of correcting, more or less in real time, its own behaviors.

Among the various possibilities proposed in this regard are the “functionalist” one just described; the “eliminativist” one, which defines consciousness as a dysfunctional anomaly or a kind of consensual hallucination; and, finally, a kind of synthesis between the two, which argues that consciousness would be nothing more than a “spy” or a “display” (completely transparent to any attempt at investigation) through which the organism would be able to self-represent and self-regulate, but which we human beings have come to mistake for something real. In any case, however, such self-representation of the body as an organism – comparable to a kind of fog hovering above or around the body – would be guilty of misleading us by giving the erroneous impression that self-representation means self-determination. For eliminativist neurophilosophy, this would be tantamount to the absurdity of a computer that, being able to interpret the pixels passing on its screen, would persuade itself that it was itself the cause of that graphic flow.

This is a clear example of how the natural sciences, conditioned by a biased view dictated by their own methodology and theoretical principles, have ended up equating human beings with their material base. An assumption that clearly clashes with the cultural developments that have emerged over the course of the past tens of thousands of years. It is not a matter of making freedom prevail over necessity or, again, of claiming some supposedly wounded human dignity. What matters is the possibility that the flow that led from a series of molecules in free fall in a vacuum to stardust and, from that, to present-day terrestrial forms of social organization, can continue to expand. The stakes, as we shall see, are very high.

The scientific tendency toward the reductionism of consciousness has raised a whole range of practical criticisms, from the so-called “hard problem of consciousness” [1], to the far more serious accusation of wanting to dismiss the issue once and for all out of mere convenience and intellectual dishonesty [2]. The real difference, however, is not between those who would have liked to venture out and those who have, instead, preferred to accommodate, but between those who wish for such flows to be channeled through new modes of existence and experience and those who believe that there is nothing else after the earthly adventure. To untie this knot, however, it is first necessary to dwell not so much on the distinction between determinism and free will as on the distinction between space and time, for it is here that much of the problem lies.

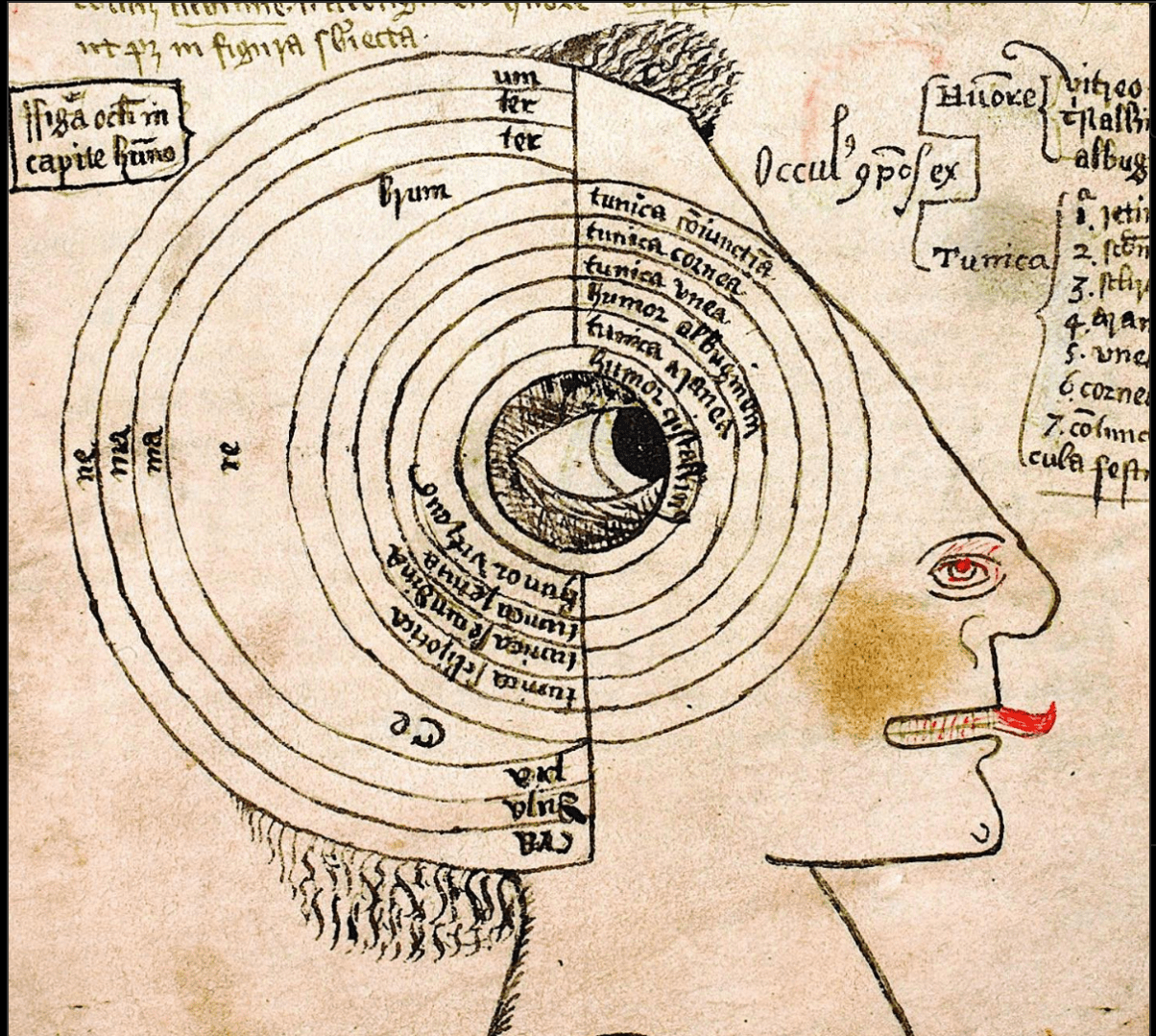

In his Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (1889), the French philosopher Henri Bergson proposed an entirely new way of thinking about the relationship between space and time – beginning a path that led him into conflict with one of the foremost authorities of his time in the field of physics, Albert Einstein. In this critical essay, Bergson examines a long series of theories and data produced by experimental psychology over the previous ten years, from Wundt’s early chronometric measurements to Fechner’s stimulus-intensity relations. Bergson’s insight regarding psychological measurements is brilliant: the fundamental error of “scientific” psychologists would have consisted in believing that the mind can be divided into precise, well-defined, and, above all, measurable segments, lines, and points. Such a fallacy could be called “the spatialization of consciousness.”

This would be a “modal” misunderstanding: in the same way that we believe (based on the precepts of naïve and folk psychology) that dreams can be interpreted culturally rather than libidinally, we are led to believe that the mind and its operations can be measured in the same way that we measure bodily movement or a basketball court. On the contrary, Bergson tells us, consciousness is something non-quantifiable, since it does not manifest itself in space like bodily reactions to stimuli but in the inner world; in such a realm, moreover, time cannot be divided into homogeneous instants and timed, since it contracts and expands in unpredictable and inscrutable ways.

This is an early sketch (preceded only by some important theoretical productions in the U.S. field) of a theory of “qualia“, that is, of those specific private mental states that can neither be detected nor communicated effectively: from the experience of seeing red to emotions, from the exact meaning of words to the relationship with the environment. Here we observe a whole series of variations in intensity rather than magnitude, in the same way that the same musical note can be perceived differently depending on context at the expense of pitch and duration.

Bergson, however, does not simply demarcate a private space for consciousness. The reference to time and its relation to mental states is further elaborated from an analysis of human affects. In fact, experimental psychologists had compiled a list of basic emotions and their behavioral correlates; a list that, for Bergson-as well as Freud after him-has no validity except in a reductionist and practical sense. For the Frenchman, natural sciences such as psychology operate cuts in the continuum of nature, abstracting extremely precise and defined segments where a certain degree, more or less pronounced, of indistinction is observed. In the field of human affect, such indistinction occurs in the intertwining and overlapping of emotions. Therefore, there would not exist “pure anger” or “pure sadness” as much as, rather, anger veined with sadness or sadness pervaded with anger, and so on. These, moreover, would also be nothing more than linguistic approximations, and we can appreciate this at the most diverse junctures of daily life: affects operate in us as a contraction of consciousness or, conversely, a dilation of it, which are always indefinite and incalculable. Hours can pass in a handful of seconds and vice versa; Bergson calls such internal temporality “duration” (durée), so as to distinguish it from the chronological and segmented temporality of the standardized time of clocks and natural sciences.

According to Bergson, it is this intensity and indistinctness that make consciousness truly free, even with respect to what it has been in the past-memory that guides action and character. The tentacles of determinism wrap themselves around matter, like the strings of an evil puppeteer, but the spirit remains unaffected, for there is no roughness to cling to. We are free precisely because we are unfractionable, unmeasurable, and, therefore, unpredictable. Memory and inner duration rise above the material world, granting Homo sapiens the insight into a higher sphere of pure freedom: a cosmic consciousness that expands in every direction.

:: :: Dilating The Mind :: ::

Psychedelic and some psychoactive substances present several points of contact with the notion of consciousness elaborated by Bergson. First of all, they introduce the subject into an entirely private inner space, within which a series of perceptual and intellectual events take place that are partly or entirely disconnected from the external world. Under the effect of such substances, time “comes off its hinges,” altering the linear succession of before and after; producing gaps, leaps, and fractures; or, transporting the subject to a temporal plane that cannot be defined except as an eternal present or, better yet, an Aion with neither beginning nor end. In this regard, among the substances with the most complex effects and, at the same time, the simplest to describe, are undoubtedly cannabinoids.

To date there is only one classic text concerning the philosophy of cannabinoids. Also found among German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s posthumous materials were a series of notes, jottings, and accounts concerning some experiments carried out between 1927 and 1934, and later published under the title On Hascisch [3]. Together with a group of friends (including the philosopher Ernst Bloch) Benjamin underwent an intensive regimen of hashish administrations for the sole purpose of testing the limits of consciousness. The results are particularly noteworthy, especially when examined in light of Bergsonian duration theory.

From the very first annotations penned by Benjamin, one can see a thinning in the perception of space, as if dimensions were crumpling in on themselves until an almost total annihilation of three-dimensionality was achieved. This is a perception well known to cannabinoid users, underlying a dilation of space and time that can make physical movement particularly intolerable.

In the following fragment, Benjamin links this distortion to a sense of anguish and even terror:

4. The two coordinates of the apartment: the basement/horizontal. Large horizontal extension of the apartment. A sequence of rooms from which music emanates. But perhaps also terror of the hallway.

According to the dictates of vulgar materialism, these kinds of alterations would concern only our particular perception and not the external world itself. Except that it is precisely the dilation of space, encountered at these and other junctures, that proves that it ultimately depends on our representation of it. This implies, in short, that no human being has ever encountered in person and, as it were, face-to-face space and what is contained in it.

There is no need to refer for the umpteenth time to Kant, Schopenhauer, or Nietzsche; it is sufficient to point out how the psychedelic and cannabinoid-induced experiences have as their particular correlate a distorted spatiality, accompanied by temporal aspects that take over. This is the case of the reoccurrence of past events in paranoid ideation; of the deep history that radiates in schizophrenia; of the abysses that open wide in front of the psychotic; of the worlds that rise out of nothingness in mystical vision: the limit experience peers through the peephole of the spirit and what it sees is more than the physical body can tolerate.

On a smaller scale, at the level of pure aesthetic experience, hashish causes inner time to exude over outer time. Or, rather, the intake of cannabinoids goes so far as to demonstrate, from an empirical point of view, that space is a swindle hatched by the evolution of species, and that time is something entirely beyond the practical use our species has made of it so far. This is what Benjamin notes on September 29, 1928, with explicit references to Bergson’s work:

My walking stick is beginning to give me special pleasure. The handle of a coffee pot suddenly seems very large, and what’s more, it continues to stay that way. […] Now the needs of space and time of the hash user come into play. And, as is well known, these are absolutely regal. Versailles, for the hash taker, is not too big, nor eternity too long. Against the background of these immense dimensions of inner experience, of absolute duration and immeasurable space, a wonderful, blissful humor lingers all the more willingly on the contingencies of the world of space and time.

:: Dilating The Cosmos ::

In the course of a debate between U.S. biologist and parapsychologist Rupert Sheldrake and Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, the latter dwelt on the mystical aspects of the psychedelic experience magnified on several occasions by the former. If Sheldrake has a paradoxically scientistic attitude toward the issue (rejecting any religious interpretation of mystical and psychedelic experiences), Žižek, on the other hand, recovers the Christian tradition, exercising one of his typical dialectical twists on it. For the Slovenian, the merit of Christian mysticism lies not in a supposed epiphanic communication between God and human being, but in the terrifying revelation of an unbridgeable distance between God and matter. Revelation is exemplified, in the Gospel, by Christ’s death on the cross and his desperate sense of having been abandoned by the Father. Let us translate this awareness on the level of psychedelic experience: since it is enough only to introduce chemicals into the body to cause a temporary disconnection of the mind from the body, it is easy to realize how this distance is already partly present in the psychophysical constitution of the individual. According to Žižek, this testifies to the nullity and barrenness of the real, but also to the exceptional nature of the self-conscious mind and the imaginative faculty. In short, what makes us truly special compared to other animals is precisely the fact that we are divided entities capable of alienation.

Too often the psychedelic subculture has focused on the unifying potential of psychoactive substances. The guiding principle of this new psychedelic optimism can be summed up in the motto “bringing body and spirit together.” But are we sure that this is exactly what we want and, more importantly, what we need?

In an essay contained in his anthology devoted to psychedelics[4] , philosopher Peter Sjöstedt-H hypothesized that, positing the truth of the Bergsonian theory of time and consciousness, we would immediately be forced to reconsider on an intellectual and scientific level the status not only of time but also of space. In fact, by asserting that spatial extension presents nothing more than a springboard for the exploration of inner and cosmic time and duration, we would also have to concede that hypothetical extraterrestrial civilizations more advanced than us have come to the same conclusion. This would entail a renunciation (more or less late, depending on the stage at which such civilizations would have been electrocuted on the Damascus road) of space navigation and a turn in the direction of psychonautics. Put simply, travel through outer space should be replaced by tripping through the inner vastness of time; in this, psychedelic substances would play a role – entirely coincidental, evolutionary rather than teleological-facilitating. The most radical hypothesis in the context of such a speculative framework is that the entities that may happen to be encountered in the course of a psychedelic trip are not mere hallucinations but sentient beings or, at any rate, capable of communication, or even other psychonauts. From a Bergsonian point of view, the dimension accessed in the course of a psychedelic experience (or the prelude to it that one is able to intuit when taking cannabinoids) is exactly that metaphysical layer in which individual memory and consciousness become cosmic memory and consciousness.

It is here that can be found what the American pragmaticist psychologist and philosopher William James described as the progressive realization of the unity of all things, a radical monism, overshadowed by a factual pluralism that, however, is only converging, day by day, thanks to scientific exploration and discovery, in the direction of its internal truth [5].

:: Santa Claus is Coming Town ::

Between the second and fifth centuries CE, a truly original new doctrine was spreading in Asia and throughout the Mediterranean region: Gnosticism (a term coined by British philosopher Henry More in 1669). Gnostic philosophers, such as Marcion, Valentinus, and Basilides, were inspired by the teachings of Plato but took some of his fundamental assumptions to the extreme. They expanded, for example, the concept of simulacrum to the entire material sphere, radicalizing the famous cave myth to the entire cosmos. Assimilating the so-called “unwritten doctrines” and cosmological theories expressed in the Platonic dialogue entitled Timaeus (c. 360 B.C.), the Gnostics argued that the sensible world was the creation of an entity as malevolent as it was devious, the Demiurge (Yaldabaoth or Jaldabaoth in the later Christian Gnostic tradition). Such a supreme being would be nothing more than a kind of clumsy “craftsman of reality” who, drawing inspiration from the study of the perfect world of ideas, would undertake to conceal the true divine essence of the world and of human beings so as to imprison the latter in a cage dominated by pain and death and be able to reign supreme over the cosmos.

As is evident, Gnostic doctrine presents itself from the outset as a complex form of philosophical and religious pessimism. A pessimism counterbalanced only by the possibility of attaining a true and incorruptible form of knowledge, Sophia, that is, the clear and distinct understanding of the Good.

Plato, however, never mentions an evil demiurge – a concept borrowed by the Gnostics, in all likelihood, from a radical interpretation of the differences between the Old and New Testaments. Nor did Platonic theories ever dwell on the recovery of polytheism, typical of some Platonic philosophers of the Roman period, such as pseudo-Micheles Psellus (author of the Chaldaean Oracles, dating from the late second century CE) and Porphyry (who lived between the third and fourth centuries CE). These are, in essence, late elaborations, born out of syncretic comparisons between schools and cultures of different origins. In this sense, it is not uncommon to encounter, within the framework of Gnostic literature, a series of entities called “archons”: emanations of the Demiurge or demonic entities charged by the Demiurge himself to govern, in the manner of feudal overlords, certain aspects of reality (from the passage of time to the orbits of the planets).

It is easy to realize how “Platonic Gnosticism,” as opposed to such “realist Gnosticism,” is but yet another myth elaborated in order to simplify the teaching of geometric-mathematical doctrines of Pythagorean origin; or to playfully illustrate ontology and metaphysics; as well as to test the soundness of classical concepts such as that of Nous – at once, the human rational faculty and the abstract cosmic intellect.

But let us strive to take seriously this kind of “neutral,” beyond-good-and-evil view of Gnosticism. In order to do so we might avail ourselves, once again, of the psychedelic experience.

We saw earlier how it is possible, in the course of a psychedelic trip, to run into certain hypothetical entities of an unknown nature; this is particularly common in Dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-induced trips, as discovered by Terence McKenna in the mid-1960s [6]. These spiritual beings, appearing in distorted and almost parodistic guise, are called “mechanical elves” (Machine Elves) because of their peculiar way of interacting with each other and their surroundings. In some ways, it is as if each mechanical elf connects and, at the same time, diverges from itself and others eternally, in an endless cycle of fractal repetition; or, as if it emerges from such an ocean in pomp, in the manner of an archdemon or archangel. What interests us most here are not the phenomenal aspects of such hallucinations (if indeed they are hallucinations), but the symbolic ones: the spring mechanisms and gears behind the mechanical elves.

Let intuition and affective associations, as Bergson suggests in Matter and Memory, take over rational thought for a moment. In the Western tradition, the most immediate reference that leads from elves to mechanisms is to the great symbol of innocence, gift-giving, and gratitude (all fundamental aspects of the psychedelic experience): Santa Claus, St. Nicholas, or, more simply, Santa Claus. That induced by DMT and the most intense psychedelic trips is a vision of the world as an immense cosmic laboratory of production. Production, as is obvious, of baubles. The Demiurge Santa Claus, aided by his troop of arch mechanical elves, turns his gaze in the direction of the Hyperuranium, the world of pure ideas; he fills his eyes with that wonder and returns swiftly to rant orders to his helpers, handing out cookies and mead with full force. It is the factory of reality, in which the gifts that every creature will find upon awakening under the Tree of Life are assembled.

Such a doctrine, however ridiculous, operates a radical overthrow in the moral and metaphysical interpretation of the world. A process of subversion that penetrates all the way into the Platonic and post-modern doctrine of the simulacrum: now (in the vein of Pierre Klossowski and Georges Bataille) it is birth that is the simulacrum of the gift package and the surprise egg; the conflict and heterotrophic nourishment of the binge of gingerbread men and gingerbread animals; the intoxication of illness and death.

The universe is transfigured in inner hyperspace, there where the Spirit broods over the catastrophe of the outer world.

:: References ::

- D. Chalmers, “Facing up to the problem of consciousness,” in Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 2, no. 3, 1995, pp. 200-219.

- This is, in essence, the position of psychedelic philosopher Peter Sjöstedt-H.

- W. Benjamin, On Haschisch, Einaudi, Milan 2010. Personally, as a purely methodological matter related to substance use, I preferred to translate all the fragments used in person.

- Ibid

- W. James, “A World of Pure Experience,” in Essays on Radical Empiricism, Quodlibet, Macerata 2009, pp. 45-48.

- For more information it would be good to start with D. McKenna and T. McKenna, The Invisible Scenario. Mind, hallucinogens and the I Ching, Inner Space, Rome 2024. It never hurts to give yourself to the practice as well.