:: On the a priori of capital in Alfred Sohn-Rethel and Nick Land ::

“If I understand you correctly, you mean to say that the transcendental subject is the head stamped on the back of our Coins?” (Walter Benjamin) (Engster 2014, 517)

“From the point of view of materialist thinking, the absolute spirit does not exist; it arises from mere belief in ghosts, which, however, is often cultivated because it can be used to justify a monopoly on domination. Idealist epistemology is based on a context of conceptual inventions, whereas materialist epistemology is based on a context of discoveries that relate to the way in which society is connected, i.e. to social synthesis…” (Sohn-Rethel 2018a, 974, translated by author)

About two months ago, @kitsumute pointed out a similarity in the positions of Alfred Sohn-Rethel and Nick Land on twitter. The indirect thesis here (as I understand it): Both read Immanuel Kant similarly as a philosopher whose theory describes a fundamental relationship between capitalism and the (non)-subject. The ideas unearthed by that post and our brief discussion continued to haunt me, leading me to write this extended exploration.

What insights can be hoped for from a comparison of the two positions? Both Land and Sohn-Rethel offer a well-founded critique of Kant, which targets some of the basic concepts of idealist and critical philosophy: The question of the conditions of thinking, which, however, can only be grasped by thinking itself and thus can never remain external to it. Kant’s critique of reason thus proves to be a rational representation of thought, in which the transcendental subjectivity of understanding appears as an absolute limit.

With Kant, the critical conceptual representation can thus grasp its own limitations and preconditions (a priori) and become aware of them. In the process, however, the conceptual representation of the thought process produces concepts that are not themselves derivable—and which, similar to pre-critical philosophy, are thus subject to a kind of transcendence. In this sense, both Land and Sohn-Rethel are interested in the preconditions of thought, which both, however, locate externally to pure reason and the transcendental preconditions of experience. Both primarily invoke the social collective field in order to liberate the transcendental and ahistorical concepts from the timeless space of the first critique—and to locate them in various forms of social syntheses. While on the surface, both approaches appear to share similar objectives regarding Kantian conceptual frameworks, close examination reveals fundamental different scopes.

In the background of this discourse there is another, much larger discourse that I can only touch on peripherally: The question of the relationship between Marxism and accelerationism and/or Land’s project. When I write about Marxism here, I am primarily referring to a specific field of theory that relates to Marx and his essential concepts of commodity, labor and surplus value. Alfred Sohn-Rethel is undoubtedly one of the most important Marxist theorists, although he also shows interesting divergences from Marx. In contrast, much of Nick Land’s work is located outside Marxist discourse.

However, Land’s early work is still assigned to a Marxist context, which is not surprising as it is brimming with Marxist references. It therefore seems quite plausible that there could be a convergence between an early Land and Sohn-Rethel if both read Kant, as a philosopher of modernity, through the historical relations of production (i.e. as a philosopher whose mode of cognition inevitably refers to historically specific economic and cultural forms of production). The process of deriving these syntheses, which I want to follow here, shows two different fields, one mainly economically determined, the other proto-cultural.

:: :: They know not what they do :: ::

Sohn-Rethel begins his analysis of the relationship of repression that manifests itself in capitalism with the separation of manual labor and intellect.

“We understand the intellect as a phenomenon, which is linked to a very specific economic social formation, from which it can be explained and even derived from, a way of thinking and understanding in which manual labor does not participate because its activity does not provide them with access to it.” (Sohn-Rethel 2018b, 721, translated by author ).

In the Western tradition of thought (which Sohn-Rethel identifies with Pythagoras, Heraclitus and Parmenides), the intellect is a continuous process of intellectual labor. Manual labor, in contrast to intellectual labor, creates products that the intellect can only perceive as phenomena. For Sohn-Rethel, the appropriation of these phenomena, the negative socialization of labour, is shown in the process of commodity exchange. Sohn-Rethel describes this process as social synthesis:

“It is the birth of the subject from the market (…) where the Greek intellectuals in Athens came together to philosophize. Manual labor is individual, the mental labor of the intellect, which is divorced from it, is social.” (Sohn Rethel, 2018c, 282A, translated by author)

The social synthesis through commodity exchange is primary—both the separation of manual and mental labor and abstract thinking itself are derived from it for Sohn-Rethel. This reformulation of Marx’s concept of the commodity fetish really understands certain thought processes as secondary activity, which derives from the primary material social being and the activity of persons. But how does Sohn-Rethel derive abstract thinking or the “autonomous intellect” from a material activity e.g the exchange of commodities? One could present Sohn-Rethel’s social synthesis as an attempt to decipher Marx’s main work Capital (Marx, 1962) with the help of early writings such as German Ideology (Marx / Engels, 1962). The concepts of the early “humanist” Marx can be found in part in Sohn-Rethel’s analyses, when he understands the exchange process in the infamous first part of Capital as an empirical and partly historical sequence of development and thus differs from a categorical Hegelian interpretation of the exchange process. As a result, Sohn-Rethel’s commodity analysis differs from Marx’s commodity analysis above all in the scope of abstract labor and the (empirical) role of exchange.

Marx begins Capital Vol.1 with an analysis of the dual nature of the commodity, which forms the basis for his investigation of the value form. According to Marx, the commodity has both an exchange value and a use value. The use value arises from the practical application of the commodity (e.g. a shovel as a tool in production or a drink as something consumable), while the exchange value arises from social relations. Through this subdivision of the commodity, Marx attempts to distinguish the different types of labor involved in its production. One aspect is the concrete, material labor required for physical production, such as a carpenter making a chair.

At the same time, a social exchange relationship is essential to enable comparability between different forms of labor. The exchange value of a commodity is therefore not derived from the concrete labour, but from the socially necessary labour time that is realized in exchange (abstract labour). However, the exchange value does not always correspond exactly to the value determined by the labor time, but only tends in this direction on average. According to Marx, value (Wert), value form (Wertform) and magnitude of value (Wertgröße) are therefore predominantly derived from the labour process and are only “realized” in the exchange process. In Sohn-Rethel’s commodity analysis, on the other hand, abstract labor does not constitute the form of value, but only defines the “empirical” quantity of value e.g the magnitude of value. (Engster 2014).

“Let us therefore note that labor does not play a constitutive role in social synthesis by means of the exchange of commodities. In the functional context of the market, it is not abstract labor but abstraction from labor that prevails.” (Sohn Rethel, 2018d, 434, translated by author)

The abstraction of exchange not only makes concrete labor abstract—it constitutes the possibility of measuring labor as abstract in the first place. In other words, exchange not only validates or realizes a potential abstraction that was already present in production—rather, the form of exchange itself creates the conditions under which we can imagine and “measure” abstract labour in the first place. Sohn-Rethel introduces the concept of real abstraction here, which is intended to describe the operation of the market participants. Real abstraction as a concept builds a bridge between the idealist concept of abstraction as a pure operation of the mind and the materialist view that abstraction (ideas) only arise from material conditions. For Sohn-Rethel, real abstractions are born out of lived economic practice, when qualitatively unequal objects are equated with each other through the commodity form and value—in other words, when qualitative properties are expressed in terms of pure quantity. These practical abstractions, which are necessary for exchange, first exist as social practice before they are perceived as mental abstractions in people’s consciousness.

“While the concepts of knowledge of nature are abstractions of thought, the economic concept of value is a real abstraction. It does not exist anywhere other than in human thought, but it does not arise from thought. It is of a direct social nature and has its origin in the spatio-temporal sphere of human interaction. It is not the persons who generate this abstraction, but the actions that do so, their actions with each other.” (Sohn Rethel, 2028c, 216, translated by author)

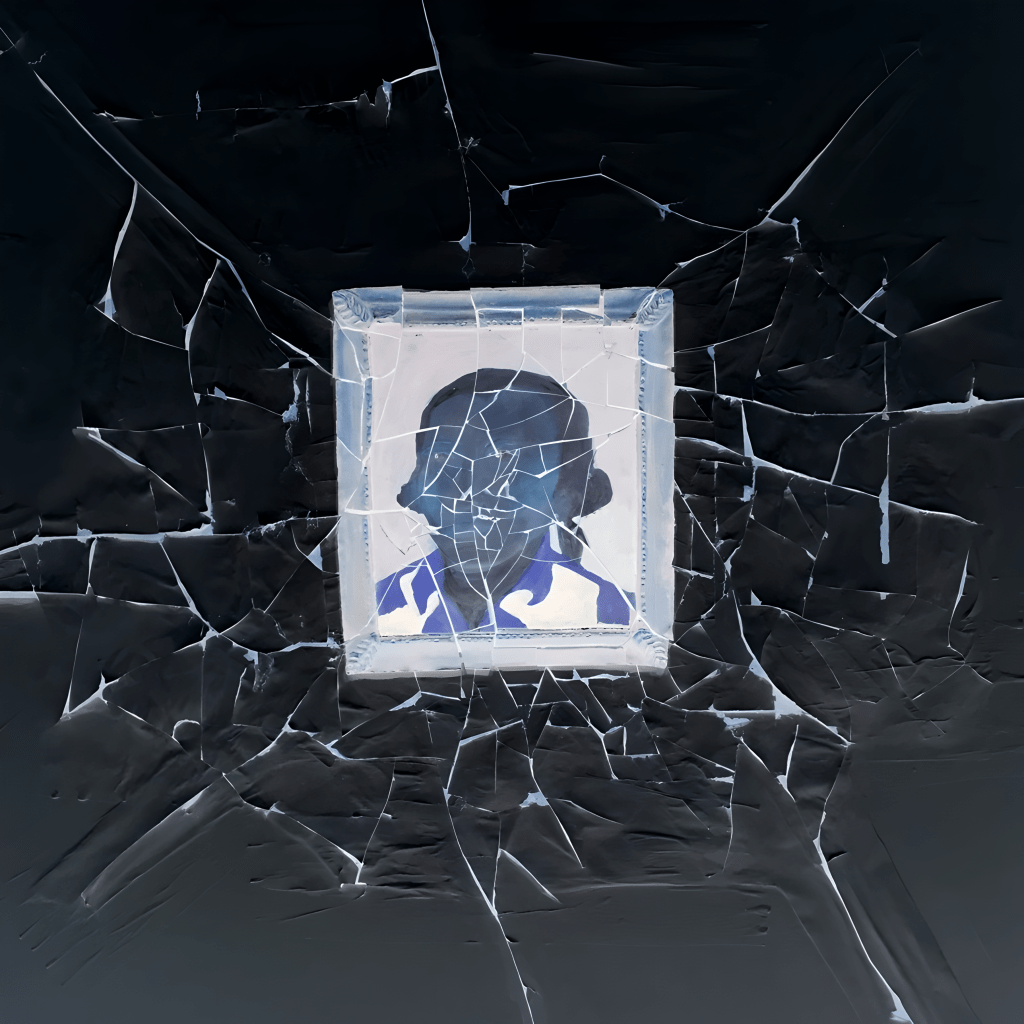

What is referred to in the quoted passage as an abstraction of thought is nothing other than concepts and subjects of Western philosophy, which always remain suspended in timelessness without history: Parmenides’ concept of substance, Pythagoras’ mathematics, Democritus’ idea of pure motion, Hegel’s spirit and Kant’s transcendental subject. For Sohn-Rethel, these concepts are fetish concepts that indirectly refer to the abstraction of value and the exchange process, but are not aware of their own genesis. The abstraction of thought thus arises as a consequence of the material economic exchange process (real abstraction) of which the subject is unaware. Historical materialism (as a “methodological postulate” and not as a completed science (Sohn Rethel, 2028c, 216, translated by author) is thus a fundamental and irreversible break with the entire idealist philosophy, since programmatically the social being and material production of human beings determines their consciousness. Sohn-Rethel thus was primarily interested in the exchange of commodities as a moment of social constitution (what Karl Reitter calls “negative socialization”), which, however, must also provide the genesis of the abstraction of thought.

If all intellectual abstractions in Western philosophy are fetish concepts, why does Sohn-Rethel specifically focus on Kantian philosophy? According to Sohn-Rethel, Kant’s concept of the transcendental subject is not only the “germinal form” (Sohn Rethel, 2018e, 60, translated by author) of the general subject that determines critical philosophy (Fichte & Hegel) but also undergoes its own liquidation in the Theses on Feuerbach. Retrospectively, therefore, not only the conditions for their dissolution can be recognized in the Kantian concepts, but also the foundation stone of a dialectic in the Marxian and Hegelian sense. Sohn-Rethel locates this foundation stone in the synthetic activity of the subject, which requires the category of time a priori. Kant’s notion of time as a category becomes only later historical for Hegel and Marx and thus redeems a truly materialist philosophy. For Sohn-Rethel, Kant’s concepts have two sides: On the one hand, they carry within them a germinal form of critical philosophy; on the other, they are fetish concepts, which must be understood as “necessarily false consciousness”. Consequently, it should be easier to prove the abstractions of thought in the Kantian forms of thought, which result from the real abstraction of commodity exchange.

In Sohn-Rethel’s analysis, the derivation of thought abstractions from real abstraction becomes especially apparent at two critical junctures in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason: first in the chapter on transcendental aesthetics (where Kant examines the pure forms of appearance), and second in the chapter on transcendental analytics (which addresses the pure concepts of understanding). Only the former will be discussed here, since the connection between abstraction of thought and the exchange of commodities is simpler than in the case of the tables of concepts of understanding. Sohn-Rethel’s argument is easy to grasp empirically: When commodities are exchanged on the market, i.e. sold and bought, the commodities themselves are constituted in the process as objects externalised to empirical space and time. The exchange itself socially produces a “standstill of nature” (Sohn Rethel, 2018f, 100, translated by author): Commodities change neither their place (the market) nor their state through time. The abstraction of thought of the two forms of sensory perception (space and time) are therefore not a priori categories but are determined by the spatio-temporal and social process of commodity exchange.

Sohn-Rethel thus relocates the transcendental subject historically, as a market participant who can only define the abstract time created by the real abstraction of commodity exchange as internal. Modern Western philosophy appears as an initial process of reflection that excludes the material conditions of knowledge production itself and thus dwells in the limited bourgeois imagination. The concepts of continental philosophy, whose genesis lies in the act of exchange, arise, like the act itself, without reflection on the traders: “They know not what they do.” (Marx, 1962, 88, translated by the author). Sohn-Rethel pays a high price for this enormous expansion of Marx’s fetish theory: since the exchange process in itself does not yet include surplus-value production (and not even abstract labour), the fetish is not constituted specifically historically but is in fact bound to ‘exchange itself’ (as an almost transhistorical concept).

:: The Great Exchange ::

Land begins his essay, Kant, Capital, and the Prohibition of Incest, by contending that the origins of the division of labor and the resulting wage labor cannot be derived from pure economic principles, but can only be explained by Marx’s original accumulation. Only through brutal displacement and expropriation does a class emerge that is forced to sell its labor on the market. However, Land does not conceptualize the market as an entirely totalising or absolute entity:

“Marx’s contention that labour trading at its natural price in an undistorted market (equal to the cost of its reproduction) will tend strongly to express an equally “natural’ refusal of the market, continues to haunt the global bourgeoisie” (Land, 2011, 58)

If the workers only earn just enough to reproduce their labour power, they would have to recognize for Land that all the surplus value they create is appropriated by the capitalists. The resulting workers’ struggles enable workers to influence the conditions of production themselves. Historical struggles such as the limitation of working time shift the relationship between surplus value and reproduction costs. Land argues that based on this historical movement, a kind of “welfare capitalism” is emerging: the working class in the western metropolises enjoys a special status that globally jeopardizes the “undistorted market price” (e.g. productive capitalist production). The economic and political improvements in working conditions in Western countries thus create a “distorted market price” (e.g. the worker is paid more than his reproduction costs) which must be continuously lowered by the import of “cheap labor”. Land has an imperialism theory in mind here, which can explain on the one hand as a continuous import of labor power, and on the other hand also the process of “freeing” this labor power as a continuous original accumulation at the periphery.

“The global labour market is easily interpreted, therefore, as a sustained demographic disaster that is systematically displaced away from the political institutions of the metropolis.” (Land, 2011, 59)

Is the constant determination of the value of the commodity labour power, which is necessary for productive capitalist production, really only endangered by the emergence of regional differences and a globalized labour market? Isn’t Land indirectly claiming that capitalists in Western countries can no longer produce capitalistically in a productive manner due to workers’ struggles, and that this necessitates a constant expansion and integration of the periphery?

The text consequently assumes that if workers not only receive the value of the food they need for reproduction, they can free themselves from the compulsion to sell their labor power in the long term. This development (which is historically evident in various workers’ struggles) can be articulated without recourse to a theory of imperialism. How does production maintain its capitalist character while the price of labor power as a commodity isn’t necessarily fixed at the cost of reproduction? The answer is to be found in the production process. The value of a certain quantity of goods produced is made up of the surplus value (the “surplus labor time”), the variable capital (the wages paid) and the constant capital (the raw materials, tools, machines) (c+v+m). Constant capital includes machines, which increase productivity as “dead labor” and continuously transfer value in the production process. If wages rise, this motivates the productive capitalist to replace parts of the variable capital with constant capital, i.e. to replace the worker with a machine. This capital-inherent process of the continuous displacement of living labor by machines, which was later placed at the center of struggles by autonomist Marxists like Antonio Negri, escapes Land’s economic part of his analysis. In a strange way, the accelerationist character of capital appears as a blank in this early text. But perhaps one should not even try (despite the Marxist vocabulary) to regard Land’s starting point here as Marxist – is it not rather Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system that predetermines the economic concepts in Land’s work?

How does this analysis of periphery and center relate to the Kantian subject? For Land, modernity (as the age of enlightenment) is characterized by an ambiguous relationship to its own ‘outside’. “Its ultimate dream is to grow whilst remaining to what it was, to touch the other without vulnerability.”(Land, 2011, 64) This constitutive process of modernity, which is referred to as ‘inhibited synthesis’, finds expression in the philosophy of the Enlightenment (and especially in Kant’s concepts):

“The paradox of enlightenment, then, is an attempt to fix a stable relation with what is radically other, since insofar as the other is rigidly positioned within a relation it is no longer fully other. (…) And this brutal denial is the effective implication of the thought of the a priori…” (Land, 2011, 64)

Kant’s discovery of synthetic a priori knowledge states that certain concepts are the precondition for every possible experience. These concepts are not just definitions (analytic) or observations (a posteriori), but rather the necessary conditions for any experience or knowledge. What interests Land here is the brutal determination inherent in this concept: it defines certain criteria to which objects of experience must be subjected in order to become ‘visible’ at all.

“Kant described his ‘Copernican revolution’ in philosophy as a shift from the question ‘what must the mind be like in order to know?” to the question ‘what must objects be like in order to be known?’” (Land, 2011, 64)

The objects of perception must be subjected to the pure forms of intuition (space and time), which Kant explains in his chapter about the Transcendental Aesthetics. Land sees this relationship as a process of homogenisation: the difference can only be grasped as the same, which then also reproduces itself as the same. Land is already very close to Sohn-Rethel’s analysis here, when he finds this process of homogenisation and quantification in market processes:

“This universal for is that which is necessary for anything to be “on offer” for experience, it is the ‘Exchange Value’ that first allows a thing to be marketed to the enlightenment mind” (Land, 2011, 67)

It can be noted at this point that in Capital, as Marxists such as Moishe Postone, among others, point out, there is already an element of quantification in the production of commodities and the expenditure of labour in relation to abstract time: abstract labour (Postone, 2003). For Land, however, this process of homogenisation is evident above all in colonial relations, which result in the previously described exchange of labour on the one hand and continuous original accumulation on the other (displacement, expropriation). Since Land is therefore primarily interested in the relationship between ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ e.g. colonised states and imperialist states, the process of social synthesis (which Land calls inhibited synthesis) is not constituted by the commodity form analysis as in Sohn-Rethel, but in trade. However, trade is not understood as a purely economic category, but is read culturally with Lévi-Strauss’s concept of dual organisation.

Lévi-Strauss regarded marriage rules and kinship systems as fundamental structures that organise societies. The practice of endogamy prescribes marriage within a social group or class. This can be within a clan, a caste, a village or another defined social unit. Lévi-Strauss saw endogamy as a way for societies to maintain their internal cohesion and preserve certain cultural or social characteristics. The opposite of this is exogamy: marriage outside one’s immediate social group, which can create alliances between groups. Can a group nevertheless maintain its social practices and reproduce itself ‘immutably’ despite an exchange of resources? Land sees dual organisation as a principle that makes this possible: through certain rules that prescribe interactions between two different groups and thus reproduce common myths and narratives. This binary structure often determines marriage patterns – members of one group must marry members of the other group (exogamy), while they are forbidden to marry within their own group (Lévi-Strauss, 1981). Thus, if Kant’s concept of the transcendental subject is ultimately the expression of a real existing lived social interaction pattern (similar to Sohn-Rethel’s real abstraction), where are traces of it to be found in Kant’s philosophy? For Land, above all in the binary organisation of Kant’s concepts:

“It should not surprise us, therefore, that Kant inherited a philosophical tradition whose decisive concepts are organized into basic couples (spirit/matter, form/content)….” (Land, 2011, 69)

It is worth reiterating on Land’s appropriation of Lévi-Strauss’s marriage rules as a theory of imperialism, as it raises some interesting questions. Land proposes the following: The relationship between metropole and imperial periphery is governed by a dual patriarchal structure that regulates the intermixing (explicitly including reproductive aspects) of both groups through codified ‘pre-cultural rules’. This emphasis on reproduction and race stems from Land’s anti-imperialist and feminist orientation, which seeks to conceptualize gender and race as foundational elements (rather than superstructural components) of production. The associated reference to Immanuel Wallerstein’s account of the emergence of the world market explains fundamental differences to a Marxist analysis such as Sohn-Rethel. For Wallerstein, the world market forms in parallel with internal national markets and even makes them possible (Wallerstein, 1986). Therefore, the constitutive moment (the social synthesis) is not abstract labour (Marx) or exchange (Sohn-Rethel), but rather trade under the doctrine of mercantilism, as the ideology of foreign trade.

Land, however, sees the universal ‘pre-cultural’ rules of a dual organisation realised in this moment of ‘trade’, which as a result seems like an anti-imperialist modification of the political concept of the ‘great exchange’. The “theory” of the great exchange posits that through a combination of mass migration, differential demographic patterns, and declining birth rates among white Europeans, a systematic demographic and cultural transformation is occurring in which white European populations are being supplanted by non-European peoples. Land is not far off: The fundamental ‘inhibited synthesis’ of capitalism is a constant exchange with the periphery (the colonised countries) in which, however, it is not the identity of the West that is erased (as in the new-right variant of this narrative), but that of the colonised countries.

:: Production, history and universalism ::

The Homo oeconomicus lives in the time horizon of a small child, so to speak; namely in an eternal present of market actions that all seem to take place on the same timeless level. If the conservative mind conjures up history in order to falsify it in the name of authority, the economic mind flogs history like pants, fighter bombers, ready-made soups and other market objects into which the tangible world is indiscriminately transformed.’ (Kurz, 2009, 30, translated by the author)

Is it feasible to synthesize Sohn-Rethel’s and Land’s propositions? Not really. Though from a broad perspective their methodologies may appear similar. Both assume a material social dimension behind the transcendental subject, behind the synthetic judgments a priori. Kant is trying to say something that he himself cannot say, is not allowed to say and cannot even articulate. The preconditions of thought are material and social, but can only be articulated by Kant himself in bourgeois fetish concepts, which are unconscious of their own origin. For Sohn-Rethel and Land, real abstraction as practice connects bourgeois concepts with social reality. The German ideology in their critique certainly resonates here:

“The sum of productive forces, capitals and forms of social relations, which every individual and every generation finds as something given, is the real ground of what philosophers have imagined as the ‘substance’ and ‘essence’ of man, what they have apotheosized and fought against (…)” (Marx / Engels, 1962, 38, translated by the author)

This results in a sad picture of the bourgeois (transcendental) subject, which is emptied and timeless and never becomes aware of its own genesis. However, while both locate the social synthesis (as a process constituting capitalism) in the sphere of circulation, the processes described differ enormously. For Sohn-Rethel, the general exchange process of the commodity is the starting point, for Land it is the colonial exchange of population as labour power, e.g. trade. Sohn-Rethel extends the Marxist analysis of the exchange movement, Land suggests ‘proto-cultural’ and universal mechanisms based on Lévi-Strauss. For Sohn-Rethel capitalism thus begins with the coin and the commodity in Ancient Greece, for Land the patriarchal clan society has never ceased, but the patriarchal dual organisation develops into the totality of modernity. Ironically, Land inevitably falls into the trap of a universalism that no longer allows for contingency: The unconditional adaptation of a ‘proto-cultural’ principle blurs all the specific peculiarities of a specific historical mode of production.

A confrontation of theoretical positions should always cause problems. The first of these concerns the definition of a specific mode of production, i.e. the historical localisation of a social synthesis. Behind both positions are questions about the relationship between base and superstructure, about ‘determination in the last instance’ and, finally, about ‘non-economic’ factors of specific modes of production. Here one should consult Louis Althusser’s essay Contradiction and Overdetermination (Althusser, 2011, 105), which distinguishes a Hegelian singular contradiction from a contiguous overdetermined Marxian contradiction: the irreducible complexity of real social production as a ‘non-linear’ dialectic. One would then have to continue to follow the historical materialism of Étienne Balibar and the schizo-universalism of Deleuze and Guatarri in order to be able to provide a contingent redefinition of the concept of basis, on the ground of real social production. This brings me to the second problem: Land never did this. Despite the precise objection that race and gender have no role in the basis of orthodox Marxism, Land never takes this critique beyond an ‘other universalism’ and remains fundamentally trapped in a Hegelian model of the singular all-determining contradiction. Xenogothic in Evil Scenius?: Reflecting on the Mythology of Nick Land points to a somehow similar conclusion:

“The problem that Land posed for the left, however, was that he was not then (nor was he ever) a Marxist. Although his first book deals with Marx’s critiques of political economy at length, Land likes capitalism.” (Xenogothic, 2024)

Even in his early work, Land was not particularly concerned with establishing a Marxist framework for discussion. Land himself appears to acknowledge this point retrospectively, noting that he employed Marxist terminology primarily as academic language—a means to situate his own ideas within academic discourse rather than as concepts he genuinely endorsed. What makes Land’s relationship to Marxism so strange is his methodological approach of reinterpretation, which is evident in the analyzed text. Land takes problems initially raised within Marxist philosophy (such as Sohn-Rethel’s interpretation of the a priori as a blind spot in bourgeois philosophy that points toward material production) and attempts to resolve them through idealistic propositions, normative sociological approaches, and ultimately classical economic theories.

To examine Land’s development of concepts like ‘cybernetic capitalism,’ the relationship between AI and production modes, and desire’s role in economic foundations requires understanding the specific problems these later texts address. One would find the ‘automated subject’ in Marx’s Capital, as well as the ‘General Intellect’ in the Grundrisse. One would find Marxists like Dieter Wolf, who conceptualised Capital as the movement structure of the absolute spirit as early as 1979 (Wolf, 1979). One would find the anti-humanism of Althusser, who describes a mode of production structurally independent from individual humans. One would need to reread Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus in its historical context to understand the violence required for Land to separate Marx from their work. This second problem, a lack of investigation into the relationship between Marxist theory and Land’s theoretical corpus, is becoming less important by the day. Right-wing accelerationism in a truly Kantian fashion has successfully overwritten all traces of its own genesis in Marxist theory with arch-bourgeois economic theory (Austrian School of Economics) and has thus made itself the useful idiot of a completely hegemonic mode of production.

:: Bibliography ::

Althusser, Louis. 2011. “Widerspruch und Überdetermination” In Für Marx. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Engster, Frank. 2014. Das Geld als Maß, Mittel und Methode. Berlin: Neofelis Verlag.

Kurz, Robert. 2009. Schwarzbuch Kapitalismus. Frankfurt: Eichborn Verlag.

Land, Nick. 2011. “Kant, Capital, and the Prohibition of Incest: A Polemical Introduction to the Configuration of Philosophy and Modernity” In Fanged Noumena – Collected Writings 1987-2007. Falmouth: Urbanomic.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1981. Die elementaren Strukturen der Verwandtschaft. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag

Marx, Karl. 1962. “Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Erster Band” In Marx Engels Werke (MEW 23), Volume 23. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1962. “Deutsche Ideologie.” In Marx Engels Werke (MEW 3), Volume 3. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Postone, Moishe. 2003. Zeit, Arbeit und gesellschaftliche Herrschaft. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018a. “Sohn-Rethel über Sohn-Rethel. Fünfzig Jahre Denken mit Marx” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 2. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018b. “Das Geld, die bare Münze des Apriori (1976/1990)” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 2. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018c. “Geistige und körperliche Arbeit (1970/1989)” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 1. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018d. “Notizen zur Kritik der Marxschen Warenanalyse(1971)” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 1. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018e. “Eine Kritik (der kantschen Erkenntnistheorie) (1957/1975)” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 1. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Sohn-Rethel, Alfred. 2018f. “Warenform und Denkform. Versuch einer Analyse des gesellschaftlichen Ursprungs des reinen Verstandes” In Geistige und körperliche Arbeit – Theoretische Schriften 1947-1990, Volume 1. Freiburg: ça ira-Verlag.

Wolf, Dieter. 1979. Hegel und Marx – Zur Bewegungsstruktur des absoluten Geistes und des Kapitals. Hamburg: VSA Verlag.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1986. Das moderne Weltsystem. Die Anfänge kapitalistischer Landwirtschaft und die europäische Weltökonomie im 16. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt: Syndikat.

Xenogothic. 2024. “Evil Scenius?: Reflecting on the Mythology of Nick Land.”

https://xenogothic.com/2025/02/19/evil-scenius-reflecting-on-the-mythology-of-nick-land/.