In the early 2010s Fred George had a problem. It’s a problem many managers of software people have had: delivering a coherent technical object when software materials are highly plastic, each developer has their own skills and preferences, and the reasons to diverge are many. Usually software architecture is the story of heroically rescuing technical coherence from the murky waters of local interests, programmer cat herding, finite resources, and crude middle manager negotiation tactics, when it is not the story of subheroic gaffer tape fudges and undelivered castles in the air. At a nexus of technocapital, chasing trading opportunities that might disappear next week, George’s advertising trading team did something else: they mostly gave up. His team of developers started building whatever they thought was important in whatever programming language or libraries they thought were useful for the problem at hand.

George called this approach Programmer Anarchy. This was a lie. There was an underlying technical rule, that everything was built as very small components of two hundred lines or less, that communicated over standard network interfaces. These components were named microservices.

Small teams that owned distinct software services were not new. From the early days of Amazon, Jeff Bezos imposed a rule that no team should be larger than the number of people fed by two large pizzas. Mel Conway long ago noted, and empirical research since has confirmed, that software component designs tend to form around the team structure of the organisation. This idea, jokingly called Conway’s Law by Fred Brooks, can be used both ways: distinct technical components help team formation; distinct development teams create distinct components in an overall software architecture. At the turn of the 21st century, network bandwidth was cheap and ubiquitous like never before. Users were communicating with websites over a network anyway, so the latencies for backend components to communicate over networks themselves were a relatively small part of the lag users experienced.

Cheap networks and the world wide web made another kind of software reuse much more common. Infrastructure of software library archives, like Perl’s CPAN, and dependency manager tools, like Apache maven, made sharing and using these libraries viable in the time economy of a software team’s day.

Software libraries of reusable standard parts had been an aspiration of software engineering since the 1970s. The functions are called in-memory, and the boundary defined is a finer-grained one usually dependent on particular mechanisms of the programming language. It might be unclear what is interface and what is internal; it might be useful to reach past officially presented interfaces to manipulate or extend objects within. The new software library infrastructure of the 21st century expanded the toolset of a working programmer in a given language from dozens of standard libraries to hundreds and then tens of thousands.

A software library defines a wide syntactic border with some protections enforced by the compiler and interpreter. A network boundary is more of a physical barrier: it just stops working when the network is busy or a cable isn’t plugged in. It also makes the interface slower, by orders of magnitude, and more complex. Suddenly operations that would just work when called within a single process need to be robust when the network is interrupted, deal with failure, conflicting callers, or out of order operations. It becomes more useful to organise around messages and events instead of sequences and transactions.

On the other hand, changing the overall system becomes easier. Each service can be versioned and released separately. As more transactions are required of the system, multiple instances of each service can be spun up to handle more parallel requests, rather than a single central system. Likewise new instances can run on new machines with similar standard hardware – scale horizontally, in the jargon – rather than increasingly enormous single machines – scaling vertically.

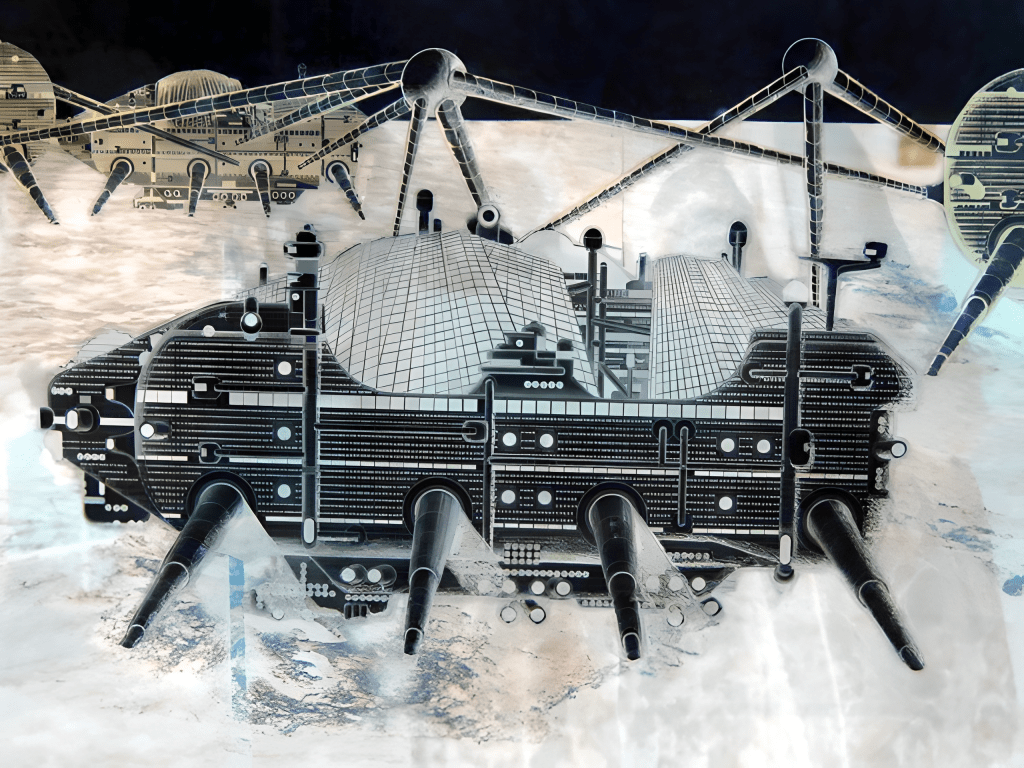

Service Oriented Architecture is the unromantic name for this approach where systems are composed of relatively independent components communicating over a network. It was all the rage in the early 2000s. A graph of interdependent components, half marketplace, half internet routing, replaces a single central point of failure.

There’s a natural fit between, say, Amazon’s two pizza teams, working independently and collaborating bilaterally, and service architectures. A team builds and runs a service and other teams make use of it. And indeed, Amazon is built around tens of thousands of internal services, visible as features within the Amazon Web Services dashboard, or separately loading elements of the cacophonous Amazon retail home page. With such an affinity between social structure and machinic structure, one might imagine that the technical components emerged organically under the genteel evolutionary pressure of Conway’s Law. Not so. Amazon has a service architecture because Jeff Bezos issued a mandate in around 2002, as uncompromising as a high modernist six lane highway pushed through a semi-industrial slum. We know the text indirectly through engineer Steve Yegge, later at Google:

- All teams will henceforth expose their data and functionality through service interfaces.

- Teams must communicate with each other through these interfaces.

- There will be no other form of interprocess communication allowed: no direct linking, no direct reads of another team’s data store, no shared-memory model, no back-doors whatsoever. The only communication allowed is via service interface calls over the network.

- It doesn’t matter what technology they use. HTTP, Corba, Pubsub, custom protocols — doesn’t matter. Bezos doesn’t care.

- All service interfaces, without exception, must be designed from the ground up to be externalizable. That is to say, the team must plan and design to be able to expose the interface to developers in the outside world. No exceptions.

- Anyone who doesn’t do this will be fired.

- Thank you; have a nice day!

Ha, ha! You 150-odd ex-Amazon folks here will of course realize immediately that #7 was a little joke I threw in, because Bezos most definitely does not give a shit about your day.

The formal difference between a regular old service and a microservice is just the size, but size plus an enforced network boundary provokes further transformation. 200 lines of code is tiny. It’s the size of an undergraduate programming assignment, before LLM coding blew them up. Even relatively small problems need to be forcibly decomposed. Each microservice can be rewritten with relatively little effort. This reduces the costs of diversity across the codebase, so many different tools and languages can be used, isolated to their own codebase and execution environment. Software container technologies like Docker make it simpler to specify exactly what library and operating system pieces are required, and run them in a separated virtual machine. As a result of all of this, components multiply, certainly in source control, but especially in production. This in turn generates an infrastructural need for interfaces, routines and tools to observe, deploy and support the mongrel herd of midget services.

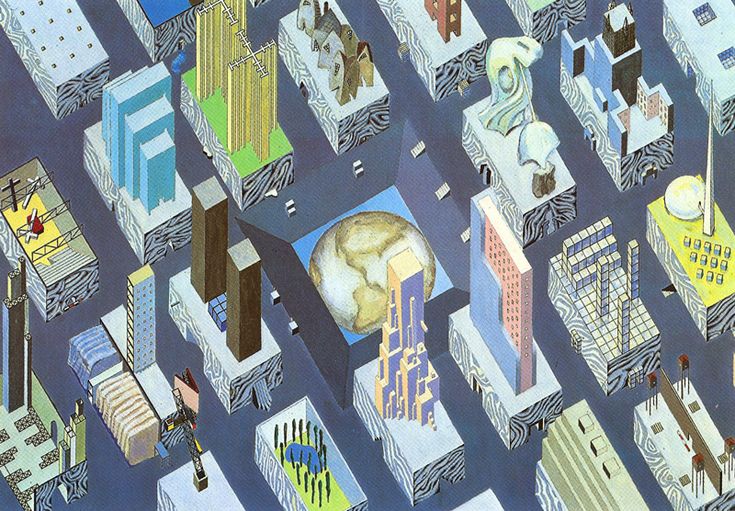

Manhattanism, according to Rem Koolhaus, is “the urbanistic doctrine that suspends irreconcilable differences between mutually exclusive positions”. In his book Delirious New York, a “retrospective manifesto”, Koolhaus lays out the ideas that make Manhattan urbanism work, the way that skyscrapers and pedestrians dominate because nothing else achieves the compressions of space and time that generate improvisational opportunities.

The grid structure of Manhattan is particularly important for Koolhaus. By dividing the city into adjacent chunks of fairly standard size, it becomes easy for one entity to swap into the same physical space as another. The physical construction of the city supports the easy transition of one physical real estate block from hotel to office to apartment block. If a growing business moves within Manhattan to get more space, it is still a similar distance for most of its customers, and has access to most of the same road, rail and communications infrastructure that underlie the entire urban grid.

Manhattan is also segmented vertically. Each floor is also a standardised container, this time stacked vertically instead of laid out in two-dimensional tiles. The steel frame and the elevator were the technical inventions which enabled it. A further conceptual innovation is needed, according to Koolhaus: Each of these artificial levels is treated as a virgin site as if the others did not exist. Each floor of a skyscraper can be a different organisation. A gym can be above an insurer above an advertiser above a deli, with the deli usually found at street level. Each entity added vertically makes the entire block more densely occupied and valuable. Each entity is another potential customer or supplier accessible at low transaction cost. Each storey added acts as vertical scaling, in almost exactly the same way as spinning up another instance of a software service.

Each skyscraper floor is segmented again horizontally, into more reusable containers, such as apartments. Each can help an existing organisation scale further, or hold some tiny new improvisational experiment. Taking up horizontal tiles with transport or communication infrastructure would dissipate valuable density, so services are pushed down into underground cables, sewers and subway lines.

The voxels of skyscrapers and the road grid provide a meta-architecture for swappable units of culture communicating cheaply and orchestrating systems of tremendous profit and sophistication. Koolhaus writes:

The Manhattan Skyscraper [is] a utopian formula for the unlimited creation of virgin sites on a single urban location. Since each of these sites is to meet its own particular programmatic destiny—beyond the architect’s control—the Skyscraper is the instrument of a new form of unknowable urbanism. In spite of its physical solidity, the Skyscraper is the great metropolitan destabilizer: it promises perpetual programmatic instability.

As for the skyscraper in urban physical terrain, so for microservice clouds in organisational computational terrain.

Thinkers such as Shannon Mattern and Scott Rodgers have written of cities as not just architecture, but also media. In Code and Clay, Mattern describes how the city is a construct for transmitting and mutating information from its very beginnings. In ancient Mesopotamia, clay was the material for written tablets and for construction buildings. Some of the first writing surfaces, clay and stone, were the same materials used to construct ancient city walls and buildings, whose facades also frequently served as substrates for written texts. A modern networked and skyscrapered city is both massively physical and densely informational; it mediates between these various materialities of intelligence, between the ether and the iron ore.

Benjamin Bratton notes that what society used to ask of architecture—the programmatic organization of social connection and disconnection of populations in space and time—it now (also) asks of software. Architecture and urban planning, in other words, are a kind of interaction design, and a kind of platform design. Manhattan(ism) is a platform which organises and constrains the ways people live and interact (in voxel containers; in close proximity) and gives up on controlling how they design and interact within those containers.

Software developers are extraordinarily fashion conscious when it comes to technology choices, and for a while there in the 2010s microservices were the new black. Without a certain level of infrastructural investment, organisational size, and technical sophistication, though, microservices don’t make any sense. It is much easier to run a few efficient components and know the entire codebase if you are a small team in a small organisation. Martin Fowler has said, like a sign on a Coney Island fairground ride, You must be this tall to use microservices, to try and make developers think about why and when they work. While it’s a useful architecture – many, indeed most, situations would do better with a monolith, Fowler says elsewhere. Microservices make sense when you have a computational coordination problem it is easy for Manhattan to solve.

Even when you have the right problem, microservices perhaps don’t quite reach the intense economies of scale of New York. One of the reasons enthusiasm for microservices cooled was that their existence in a graph of bilateral connections requires a maintenance bureaucracy of routing, tracing and permissioning. Most of these elements are resolved concretely in an urban grid just by choosing a location. The street grid establishes communication between buildings using a single address, behaving more like a universal service bus than a quadratic nest of point to point strings between related entities. Alternative routing around points of failure, like roadworks, is also built in for free. No new ticket or license is required. Just walk around.

You must be this high to use microservices.

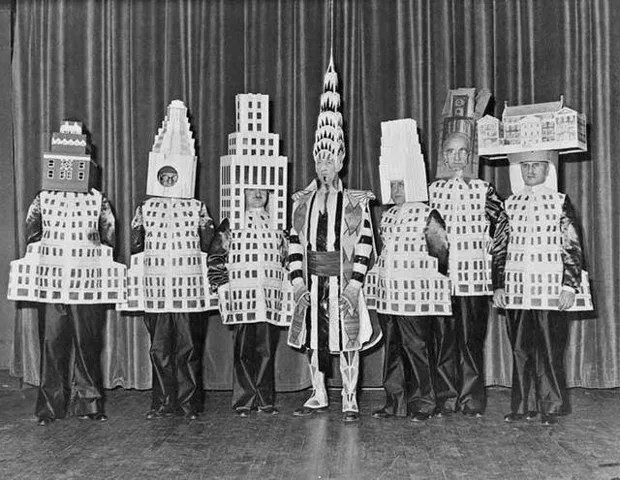

[Architects at the Beux Arts Ball]

Le Corbusier, the high priest of high modernist architecture, loved skyscrapers and hated Manhattan. It was too ornamental, too congested, too unkind to cars. Corbusier pushed an alternative vision Koolhaus calls the Anti-Manhattan: horizontal skyscrapers, giant brutalist and glass rectangles that stretch for dozens of blocks, populated by one organisation, surrounded by corporate lawns, in a dedicated part of town, commuted to by car.

This is where Service Oriented Architecture starts. Big, functionally separated services running on separate hardware, connected by network freeways, designed top down. The Machine for Storing is in a separate computational district from the Machine for Business Logic and the Machine For Presenting to Users. Then at the end of the day workers drive home to their Machine For Living, eat dinner and ask their kids how the Machine For Learning was today. Maybe the software architect even used the Rational Unified Process, a suite of tools and bureaucratic diagramming techniques from the 1990s and early 2000s, named like the lovechild of Rene Descartes and an IBM mainframe.

Jeff Bezos’s services mandate came down like a high modernist decree from Robert Moses. But it was a memo, not a blueprint. Bezos was sometimes a micromanager at Amazon. That same Steve Yegge rant from which we learned about the Bezos services mandate notes how Bezos also headhunted Larry Tesler from Apple to redesign the Amazon retail store homepage. That homepage, then and now, is inspired more by a popcorn maker explosion at a flea market than any tradition of sleek, focused, industrial design, and Jeff rejected every suggestion Tesler ever made. I wonder if Bezos just loved the congestion, like a throwback to his time on Wall Street, the way the dense everythingness of the page evoked how he wanted Amazon to be the everything store. But at the end of the day, he only micromanaged some things. Elsewhere, he sent his executive enforcers to make sure everything would become APIs and services, and then left it to those individually accountable, individually fireable, two-pizza teams.

Buildings are more plastic than they look, and the walls of software are much more plastic than the walls of buildings. (Yet a well-used relational database will persist longer than many buildings.) So Amazon rewrote itself around thousands of services, and then it has kept rewriting itself around services. Some are critical; some are experimental. Benedict Evans describes Amazon as a combined sociotechnical grid of infrastructure and teams:

Amazon at its core is two platforms – the physical logistics platform and the ecommerce platform. Sitting on top of those, there is radical decentralization: Amazon is hundreds of small, decentralized, atomized teams sitting on top of standardised common internal systems.

Because it constantly behaves as a platform towards itself, with all the overhead and elbows-out competitive redundancy that implies, Amazon finds it easy to turn itself inside out, both in integrating suppliers and gazumping them with cheaper duplicates. It also oscillates between being a marketplace and a supermarket, depending on what is most profitable at the time. The most spectacular example of this was the launch of Amazon Web Services (AWS) itself, where it surprised almost everyone by suddenly selling cloud compute services externally the way it had sold them internally for years. “Amazon, then, is a machine to make a machine – it is a machine to make more Amazon,” as Evans puts it. Isn’t that also Manhattan? The city that makes a city. Delirious technocapital.

Le Corbusier eventually won a beachhead in New York. And what a beachhead: the United Nations General Assembly building, the paradigm of mid-twentieth century high modernist technocrat utopianism. And though Corbs was just one member of a ten person committee, it was still an International Style gang, with plenty of hallmark features. Instead of being tall and thin, it’s short and long: a mere four storeys, but over a hundred metres long. The Secretariat Building next door tries to fit in a bit more, reaching 39 storeys, like a mid-level career diplomat dutifully joining in a dance at the edge of a rather more energetic party. Part of the site is given over to New York’s most boring park. But though the entire headquarters takes up seven hectares of prime riverfront metropolitan real estate at self-importantly low density, Koolhaus notes that the point of ingress stopped there. Manhattan simply enveloped the contradiction. The easiest way to get there is still walking from a subway station. The park attracted some handsome political ornaments, with Saint George and the dragon upstaging austere geometry. Like an oversized service monolith surrounded by independent microservices, it still fits into the Manhattan grid, like the Guggenheim Museum, or the vital infrastructure of Central Park.

Fred George was presenting at a conference for programmers when he called his team’s approach Programmer Anarchy. It was even an Agile Software Development conference, at a time when that term was still more associated with technologist empowerment instead of high cadence management surveillance. Both the Agile Manifesto and Manhattanism camouflage utopia in smart business clothes. From the supposedly insatiable demands of ‘business’ and from the fact that Manhattan is an island, the builders construct the twin alibis that lend the Skyscraper the legitimacy of being inevitable, Koolhaus observes. [T]he incipient tradition of Fantastic Technology is disguised as pragmatic technology.

Now material on microservices focuses more on how to domesticate them. The strict line of code limit has mostly disappeared, replaced with more of a one-small-concept vibe, but the constraints of automated deployment, independence, and networked communication are still routine parts of the definition. I’ve never met Fred George, but I wouldn’t be surprised if his original team required a bit of pushing to get started, being brought under the new meta-architectural rule, just as the Amazon teams did. Most successful managers have a bit of prick in them. Today, as I am writing this, if you google “microservices”, the top result is a page from Amazon selling AWS cloud solutions.

It’s a pretty good overview.

REFERENCES

Benjamin Bratton (2015) – The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

Mel Conway (1967) – How Commitees Invent. Datamation.

Benedict Evans (2017) – The Amazon Machine https://www.ben-evans.com/benedictevans/2017/12/12/the-amazon-machine

Martin Fowler (2014) – Microservice Prerequisites

https://martinfowler.com/bliki/MicroservicePrerequisites.html

Martin Fowler (2019) – Microservices Guide https://martinfowler.com/microservices/

Fred George (2012) – Programmer Anarchy https://youtu.be/uk-CF7klLdA?si=61Fh3c7cuM9fkvyk

Rem Koolhaus (1994) – Delirious New York. 20th anniversary ed.

Shannon Mattern (2017) – Code + Clay … Data + Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media

Rodgers and Moore (2018) – Platform Urbanism, an Introduction https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2018/10/platform-urbanism-an-introduction/

Steve Yegge (2011) – Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant https://gist.github.com/kislayverma/d48b84db1ac5d737715e8319bd4dd368

Adam Burke blogs over at Conflated Automatons.