Carl (Christian) Olsson is a writer and theorist working with histories and philosophies of science and spatial theory. His work touches on the human self-image, different concepts of freedom in nature, and transcendental philosophy. Carl recently completed a PhD in Human Geography at Newcastle University. He contributed to the second cycle of The Terraforming at Strelka Institute, has been a visiting scholar at Waseda University, and is an instructor at The New Centre for Research & Practice. He has written for Urbanomic, ŠUM, and different geography journals and edited books.

DIFFRACTIONS: Could you reflect on how you approach the intersection of transcendental philosophy, geography, and human self-perception within planetary processes? What personal experiences or formative ideas have shaped your theoretical work?

Carl Olsson: First of all, thank you for this opportunity to think through some aspects of my work from the past few years. I suspect many people who work on philosophical topics are driven by certain problems that compel them. In the beginning we have no idea what they are. Then we go around for a while and try to figure out what these problems are, wandering from topic to topic in a more or less disorderly manner. Then, after some years, we realize that we have been working on the same thing all along without having been able to articulate it except in highly manneristic ways. I’ve always felt I came to philosophy quite late in my mid-twenties, but in hindsight this might not be true. I always feel late to things in general – perhaps because I ended up retaking a year of high school. By training I’m a cultural geographer, so I never really took any philosophy classes. Geography is perhaps the most conservative discipline there is in terms of its philosophy, by the way. As a discipline, it has been in a state of existential crisis and confusion about itself for more than a century. Very few people appear to have thought seriously about what geography is, so there is some low-hanging fruit.

In any case, I think the question requires a personal answer rather than a theoretical one because my trajectory seems determined by my problems. So when I was an undergraduate, I went on this student exchange to Osaka University. I have celiac disease, and it turns out there is gluten in basically all Japanese food. To describe my experience, it was like walking around, starving, in an abundant garden, knowing that all the fruits are filled with a poison tailor-made for me. We were like twenty-four people sharing a small kitchen, but there was this chain restaurant where they had one thing that was officially gluten-free (though in hindsight almost certainly cross-contaminated) where I would eat almost every day. You can see the entire thing was an absolute disaster. Anyway, there was one student who was totally obsessed with Hegel. We didn’t get along at all, but I was intrigued by her dedication. So when I came home, I started to read some theory-heavy texts in geography and branched out from there. Soon afterward I found Deleuze and became obsessed because I understood nothing. It took about four years until I actually talked to someone else who read the same literature, and I suspect the self-study helped me develop an independent position of sorts. Then I failed to get into my PhD program for a year. In Sweden and a few other Northern European countries, we have something called Folk High Schools, which are essentially pre-University level and offer a variety of courses that are often practically oriented. I ended up in a crafts and design course oriented toward building furniture and things, but instead of doing what I was supposed to, I started painting. There’s this passage in A Thousand Plateaus on faciality where Deleuze and Guattari talk about the fungibility of face and landscape that became quite important to me.[1] Before I stopped, I painted a bunch of portraits, and I suppose I was already on the way to thinking that geography has nothing to do with the landscape motif despite the vast literature on that connection. The content of (human) geographical thought is much closer to the self-portrait: a system of a figure designated as a self and a world which surrounds it. To be precise, geography seems to work like an inhabitable self-portrait. If so, geography is irreducible to its incarnation as a historical discipline. It would be better understood as a cognitive action.

But what is a cognitive action? I cannot imagine that the first models of the world were created by anything but hungry microorganisms. To be able to find nutrition reliably, it is beneficial to be able to distinguish prey items from both oneself and irrelevant things in the surroundings. As animals became quite good at forming images of objects and possessed a sense of self, it became possible to cognize oneself in the same terms as other objects. Geography begins when hunters turn inward. We have since become quite good at performing intricate conceptual moves with ourselves as fully fledged objects in the world. I think a real reason for why I came to a position like this is owed to the year I was basically malnourished. Even if those events were ultimately self-imposed and solvable if things had gotten really bad, I suspect it is actually really hard to appreciate our animal nature without having experienced food scarcity for an extended period of time.

That is, broadly, how I came to be where I am right now, which is to say unemployed. If I have any capability as a philosopher, it is probably because I routinely become obsessed with figuring things out. I’m not very technically proficient, nor am I exceptionally well-read. But I do think I have a distinctive sense of dark humor, which I’m willing to follow to its conclusions.

DIFF: Your work also brings together a constellation of thinkers such as Wilfrid Sellars, Kathryn Yusoff, and Reza Negarestani to inform your approach to geographical thinking. Could you elaborate specifically on how Sellars shapes your theoretical orientation around the Anthropocene, especially in thinking through a bridge between manifest and scientific images and in addressing the tension between human agency as an impersonal planetary force and as a locus of ethical and political responsibility?

CO: I suppose people knowledgeable about Sellars should find me a bit superficial. I am mostly interested in some of the more accessible aspects of his thought. Still, I think the distinction between the manifest and scientific images has perhaps not been used to its full potential. [2] This seemingly simple distinction is a remarkable contribution to the philosophy of geography. While many thinkers have noticed a seeming contradiction between how we experience ourselves in the world and what the sciences say that we are, Sellars’ notion of conflicting images hits on something rather unique? What sort of images are these? They are images of ‘man in the world,’ of a figure surrounded by a ground. In other words, they are veritable self-portraits, which, if I am right about geography’s grammar, makes their clash something that transpires within geography. I’m not really working on the Anthropocene right now, but to say something, I believe its significance as a geographical concept lies in how it helped us think about ourselves in scientific-image terms, which cast us as relatively small. The clash between the manifest and scientific images has typically been invoked with a view to microscopic particles, whereas the Anthropocene thesis forcibly casts us as causal components of a system much larger than ourselves. I don’t think we can expect anything like a final resolution to the clash between Sellars’ images, but I do believe his distinction gives us some tools to see what sort of conceptual trade-offs will be involved in the geographical task of navigating through the present state of the Earth Systems we participate in.

Now, since you mention Kathryn Yusoff and Negarestani, their work provides some tools for me to respond to what I think is also at stake in your question. Both are thinkers whose work has been of methodological and direct relevance to me, each in slightly different ways. I have only met Yusoff briefly, but the way I look at her work, her trajectory appears to start with a significant affinity with new materialist thought. There are influences from Deleuze, Grosz, and Colebrook in her papers, which are often about how geographical and geological environments shape human life. In her more recent work, which has built up to her Geologic Life,3 there has been a gradual inversion that places knowledge at the center. Spatial practices (forms of geology) are now equally seen to be productive of human beings by their capacity to render people fungible with matter. While the history of geology cannot be divorced from the racial dimension of its effects, its violence having been directed by and large toward people of color and indigenous groups, Yusoff also draws attention to the grammatical aspect. There is something about how the semantics and syntax of spatial knowledge have direct effects on the world, which inherently make knowing space its own determinable spatial phenomenon. I think this is a marvelous trajectory for a geographer. Now, I still think there is a lot of work to do on what these grammars are and how they vary between different spatial practices. What has been interesting for me is to find pseudo-analogies that extend quite far beyond human history so that we can have some tools to contextualize what it is we do when we determine space. ‘This is a mountain,’ ‘that is a bush’ – what do such determinations presuppose when they are asked in the geographical mode that make them, I guess, inhabitable portraits? What other phenomena does the grammar of inhabitable portraits echo?

For me this becomes a question rooted in the grammatical predation, which comes with a sort of indelible violence. There appears to be a presumption among geographers that we can do geography better and less violently so as to dissociate the discipline from its colonial and military past, as though these were just unfortunate coincidences. Alongside a few other writers, Yusoff is showing that this presumption might not be entirely correct. There may be something violent about geography as such. This is not to contest that geography can be done in different ways, some of which are better and some of which are worse. The point is that before the ethics of how to do geography can be raised as a question, there is a layer of essential violence inherent in the geographical way of determining things.

Few people have written more incisively on the violence of determination than Antonin Artaud. He seems to have returned to this problem incessantly throughout his life. Throughout the first year of my PhD, I was fairly lonely and ended up reading Artaud literally every day in an attempt to figure out his potential relevance to geographical thought. I don’t think this was particularly healthy, but ultimately it proved useful. I have my own impatience for the cruelty that things exercise upon us: I get way too angry when there is food stuck on a plate after I wash it or when I try to fix a bike. There is always a kind of friction when we try to act on things – as if they try to control us in turn. Geography is a way to empower ourselves against the world. Maybe I started doing philosophy in response to my inability to engage with the world in a healthy way. What started as maladaptive escapism became its own end.

All this said, I think there are few things less interesting than the blanket statement that everything is violence. Ethically it leads nowhere. Those who are called by this type of thought, belief, or experience must be careful to consider the specifics: what sort of escapism does it lead to? What is the grammatical form that makes the violence of an act indelible, and what other acts does it resemble? We need to be precise about these things to avoid clichés.

As for Reza, I always read his work with horror. Sometimes we encounter people who have already been everywhere we wish to go. Whenever I talk to Reza or read his work, I get this strong feeling that I am too late and should probably quit philosophy. I have been able to leave Deleuze behind in the sense of articulating a philosophical problem that departs from his work but leads elsewhere. But Reza seems to have been everywhere I try to go. It is awful, and the way my interests are structured means that I have little hope of committing myself to going in a different direction. I am not, as it were, capable of doing what it takes to go further. And this is where I admire Reza the most, namely his ability to restart and find a new direction, not recklessly or gratuitously, but when it is philosophically required. Very few philosophers are capable of doing this with so little compromise.

Reza’s idea that the concept of the human is a revisable hypothesis[4] has been important to me, but even more so, I think, when it is connected to the notion of a thorough ‘critique of transcendental structures,’[5] a lot of room suddenly opens up. I probably understand this a bit differently than Reza because I am more of an unreformed Kantian, but as I see it, the key question is: ‘What does it mean for something to be a self-revision anyway?’ Clearly, geography, as I have construed it, is all about determining the human being. It is as if by way of representing ourselves in the world, we get a chance to actually transform ourselves, certainly not in a direct way (‘I am Nero’ does not make me the emperor of Rome) but in some way. But if these kinds of transformations rely on a specifiable grammar, it also means that there are some constraints. We can try to find out what they are. So if there is a natural historical dimension of my interest in geography’s grammar (the pseudo-analogies I mentioned), there is also a critical dimension intent on finding the limits. In this essentially post-Kantian endeavor, I believe specificity is indispensable. If we are attempting a critique of transcendental structures that is thoroughgoing, that has to mean identifying a particular explicandum and positing an equally particular explicans. Any transcendental story we tell will, of course, be subject to overdetermination in the sense that any act is constrained by an effectively infinite number of variables.

In philosophy, I think the goal is not to be exhaustive but rather to identify some variable or other that leads to an interesting story when it is used to explicate the target action. I know this may sound abstract, but to stay with the example of geography, I have tried to explicate it by positioning it in relation to natural phenomena that most resemble it, like other systems of figure and ground. In each of these systems there are certain things that just have to be in place for them to be what they are. It is hard to think of a portrait that does not, in a logical sense, consist of a figure-ground relationship. I think Christine Korsgaard and others who have developed a constitutivist position in metaethics have a lot to say about the structure of cases like this.[6] So as to circle back to your question, to understand what positioning ourselves in the Anthropocene means and the particular challenges that come with it, we have to also think through these questions about what goes into self-representation to begin with. This is perhaps what can be contributed by people who feel like they have to run away from things.

DIFF: In your article Naturalism and the Self-Effacement of the Non-Representational Subject, you argue that attempts to naturalize subjectivity in early non-representational and materialist theory risk becoming overly literal, conflating what subjectivity is with what a subject does. How might attempts to naturalize subjectivity risk undermining both the conceptual integrity and practical agency of the ‘subject,’ and what insights does this offer into the spatial dimensions of geographical thought?

CO: Just to give some brief background, non-representational theory was this moment in the late 90s-early 00s where mostly British cultural geographers tried to revive their discipline by bringing it into the world. The narrative was sort of that geographers have been too distant and narrative without proper attention to the lived, bodily aspects of inhabiting the environment. It was a highly syncretic moment, which makes it a bit difficult to summarize, but it notably involved an encounter with Deleuze and Guattari mediated by Rosi Braidotti and Elizabeth Grosz as well as reckonings with Latour, performance theories, and a fair bit of phenomenology. In practice, this led to a lot of methodological experiments with dance, performance, and autoethnographical accounts of inhabiting the world that have been a lasting influence on cultural geography. I also think it has had a clandestine impact beyond geography: if I recall correctly, I believe Jane Bennett thanks Nigel Thrift (one of the original synthesists) in her Vibrant Matter.[7]

So, if geography is a realization of our ability to revise our account of who we are, it matters because such revisions achieve something. What do they achieve? As far as I am concerned, they modify our relationship to the environment. I mean this in an ecological sense. An organism that can revise its understanding of itself can do certain things in virtue of adhering to the grammar of revision. Ok, but what happens when it undertakes a revision that breaks with the grammar of being an agent of revisions? There is a kind of performative contradiction that happens here, and historically, this can be seen in the threat of unrestrained naturalism that leaves no conceptual space for free action. This is the old problem of reconciling freedom and nature that became so important after Kant and which, already with Fichte, led to an insistence on the logical primacy of freedom. Why? Because a conceptual determination involves representing oneself as free. What has perhaps not been seen so readily is the geographical aspect of the problem. But it is geographical insofar as geography is the art of representing the self in the environment. In response, it might be possible to tell a story about how geographical thought has undertaken all sorts of strange turns to insulate itself from the consequences of a naturalistic self-understanding. It is extremely weird that the place where the problem of nature and freedom seemingly ought to matter most has almost completely ignored it. How come?

Perhaps it is because the problem is itself poisonous. Perhaps geography operates precisely because of an ignorance that is properly speaking transcendental. To this day geographers construct extremely elaborate theoretical accounts and ontological stories without ever really considering what consequences these stories would have for themselves as geographers. Even the contemporary tendency to emphasize situated knowledge is almost fully devolved to stories about the self rather than to the conditions according to which this self is posited. What has become known as non-representational theory is especially interesting because the contradictions are so plain in these explicit attempts to turn geography into space – into things as they happen. At some point one has to ask when geography ends and dance begins. The upshot is, of course, that geography did not come to an end or anything like it, so above all I think non-rep revealed something about how geography operates to protect itself. If the proponents of non-rep actually did what they said they did and became indiscernible from space, they really did test a limit of geography by exploring the limit of the grammar of self-revision.

DIFF: Your work traces the figure of the gymnast as embodying an ‘imaginative geology’ and an anti-planetary practice, reclaiming bodily freedom shaped by historical shifts in posture and mechanical forces. Could you elaborate on how the gymnast’s ‘struggle’ reflects the broader tension between human autonomy and planetary constraints? In other words, how does this embodied negotiation bring into view the ways in which our physical and practical horizon is structured by planetary forces, and how might it resist or reconfigure them?

CO: Whereas up until this point I have been talking about geography as a type of cognitive action, I have also done a bit of work to highlight individual instances of geographical thought. I sort of like to assume that geographical knowledge is produced by a lot of different people, not all of whom are recognizable as geographers at first sight. If we think about geography as a cognitive action rather than as a discipline, this makes a lot of sense. So I try to reconstruct some strange self-portraits to show this. Incidentally, I think the notion of anti-planetary practice is also a good example of what I mean by following things to their conclusions.

A couple of years ago, I went through a breakup and moved to a different city. A close friend suggested I come with her to the gym. Almost overnight I got really into that and would wake up at 6AM almost every morning to train. I started reading anatomy and biomechanics textbooks and so on. The animal body, considered from a mechanical perspective, is a very interesting geographical space that few in the discipline appear to have examined seriously. So that is one of the things I am trying to work through at the moment. The astrophysical perspective of planets that is being emphasized by some philosophers like Lukáš Likavčan and Bronislaw Szerszynski is an obvious connection for me here.[8] So you can see a general method here: I’m working on a project and have certain ideas in mind, and then there is an encounter or something in the world that catches my attention so as to provide a kind of lever on what was already there. I suspect many people work like this.

In any case, the gymnast is simply a character who, in virtue of what they do, moves directly opposite the Earth’s gravity. Clearly, their capacity to do this depends on their physiology, which over the course of evolution has been constantly constrained and enabled by various Earthly environments some of which are literally global in scope. Earth’s gravity is essentially ubiquitous throughout life’s history even if its impact is highly differentiated due to distance and the presence of different media (e.g. water). But there is also something that is sick about gymnastics in the philosophical sense I’ve tried to outline: of all the factors that constrain life, why should we be so excessively concerned about one in particular? There is not really a good normative answer here, I think, but merely a recognition that sometimes we are. People can become enamored with a lot of different ways of positioning themselves in space. Likewise, we can channel these almost obsessive concerns to think about our past and present from perspectives that change how we appear, which is to say that we can use them for building geographical stories.

You’ve asked about freedom in nature a couple of times, and this is probably the place to answer. In this particular narrative, as in most things I write, there is a movement between positive and negative accounts of freedom (thematized by Isaiah Berlin as far as I can tell).[9] Where positive freedom is an ability to do something (such as jump because we have legs and Earth’s gravity pulls us back down), negative freedom is a liberty from a restraining factor (the prospect of an escape from Earth). I think the paradoxes that arise when these two concepts of freedom, which both pervade our everyday experiences, come into conflict often lead to great philosophical stories.

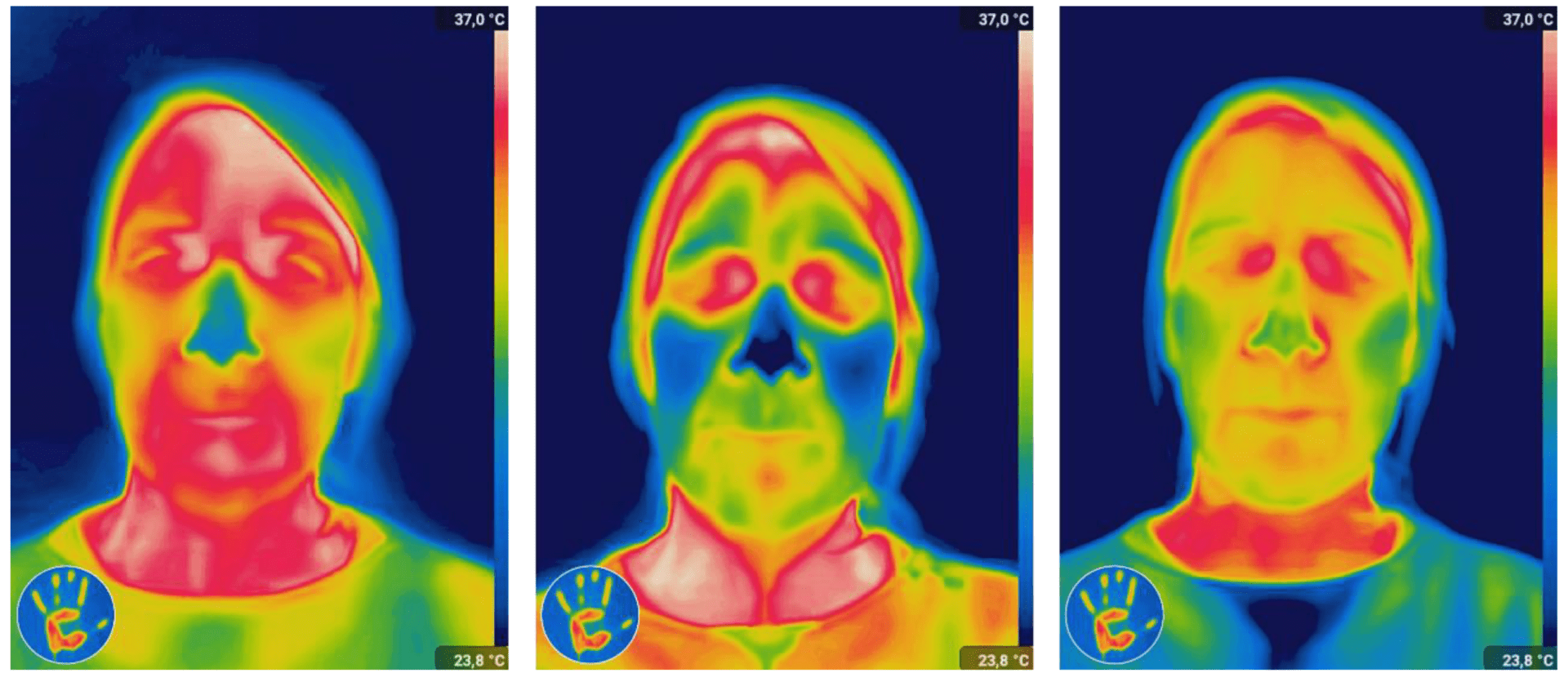

DIFF: I’d like to pivot to your essay, Peak Face for Urbanomic. Considering the centrality of the face in shaping evolutionary biology, social cognition, and planetary organization over hundreds of millions of years, how might a post-peak-face era, characterized by faceless computational intelligences and morphodiverse cognitive architectures, transform our “noosphere” as well as the ontologies of selfhood, sociality, and perception?

CO: The Peak Face essay came from a short video I did with my friends María Buey González and M. C. Abbott.[10] The essay, while its own thing, built on this video, so I just want to recognize that. I said before that I painted portraits for a while, and I sometimes feel a bit sad that I quit. But it became impossible, and I got completely lost in trying to keep the figure together. Peak Face was personally important in light of this trajectory because it created some closure. I really do think of it as a sort of ultimate portrait – a conceptual machine that would capture every face that has existed or will exist in the future.

There are so many ways to imagine the future of the face once it is liberated from its association with the human. For me, one of the most interesting story lines is that the face may have been a local maximum of sorts. It became a dominant interface either by chance or because there is something about planets that makes body plans suitable for faces adaptive. But it might be that if we move our perspective sufficiently far away in time or space, there will be a transition away from the face. What might be useful in this context is to use the concept of ‘interface’ as a material foundation for how different types of intelligent systems can interact with the environment. What Peak Face did in relationship to the face historically may be possible in relation to other interfaces too. In this broader sense an interface would be something that encompasses both input and output, and what we call a “face” is a highly pervasive and deeply entrenched historical type of interface. Imagining different interfaces is actually not particularly arcane. The USB standard is a pretty good example of how a faceless architecture can be set up even in a facial world. We seem to already be well on our way to defacing Earth.

The other interesting possibility is that perhaps our bilateral bodies lend themselves to a particular structure of thought or what might be called transcendental structures rooted in our anatomy. If so, it might well be possible to imagine what a faceless future looks like in terms of architecture, but it might be harder to think a faceless thought. I am working on a project which combines these story lines at the moment, so I don’t want to say too much right now. Instead, a more grounded approach can be found in Patrick Gamez’s recent book about surveillance capitalism which presents some interesting ideas about making a faceless future serve us.11

DIFF: Finally, building on your work with Lukáš Likavčan, if artificial neural networks act as ‘mirrors’ that let humans rethink their own cognition, how might geography confront the spatial uncanny of machine intelligence? To what extent, if at all, could we consider the Anthropocene obsolete? Moreover, how could we also situate machine intelligence within the notion of the ‘inhuman’ (Negarestani, 2014) and a widened aperture of planetary-scale processes?

CO: So to situate what I’d like to say, let’s entertain the existence of two orthogonal philosophical responses to the rise of new technologies and other environmental changes. This is probably not a good typology, but let’s see where it leads: One response is focused on the consequences for the world and merges philosophy with a kind of futurology. Someone who responds this way may want to follow the new technology to its conclusion. How will generative AI change our conditions? Will we all die? How are we going to live in the Anthropocene? The other kind of response is more existentially focused because it is principally concerned with what will happen to our self-understanding. Let’s call it humanistic. What does AI tell us about human cognition? How might we understand ourselves and our place in the world now? While I think that my interests belong to the humanistic response in some way, it can descend into a type of parochial conservatism á la late Heidegger.

Nevertheless, I do believe it is worthwhile to think about revolutionary change in terms of its effects on our concepts – specifically its effects on what we make of ourselves. But the scales and frames of reference need to be opened up for this humanism to lead anywhere. Parochialism can be defeated by sufficient alienation. ‘Peak Face’ is a pretty good example of this too because it places everything that is happening now in terms of facial technologies on a completely different time scale. All too often philosophers find themselves looking at the human in terms of what is most intimate and, therefore, in a sense, least interesting. From this perspective, I have to be honest and say that I don’t find any recent technology particularly uncanny, though there are of course many interesting consequences of planetary-scale sensing and so on. But we should not forget that except for a few circumstances, humans have never been the most consequential agents of spatial change on a planetary scale. Had the Anthropocene been formalized, it would have been as an epoch, which is basically at the bottom of the hierarchy of the geological timescale. In the grand scheme of things, it would not have been that revolutionary – especially not from the viewpoint of human self-understanding. So, to answer your question in a direct way, I do agree that the Anthropocene is now an obsolete notion, but I also think there was never that much at stake because planetary-scale thinking would be possible without it.

We live in a time where we tend to think that everything new is revolutionary. That makes sense per se. But in philosophy it is interesting to be a bit more careful. When it comes to how we understand ourselves, change can take time. I absolutely don’t think we adequately reckoned with Darwin and how the theory of evolution makes, for example, the idea of eugenics possible. I think that is a good example of genuine revolution. What we know of our nature is already so alien to our everyday lives that things like processing natural language by artificial means should not surprise us at all. While generative AI and the like are obviously consequential for society and remarkable feats of engineering, I’m not so sure how we should assess the philosophical implications. We obviously already knew that language is a medium for reasoning, just as we knew that there are many types of intelligence. For me, the chapter I wrote with Lukáš about looking at ourselves through a weird mirror was done in an interrogative mood. If there is going to be something like a Copernican revolution, it may take a long time to arrive. The rubric of Copernicanism was always a marketing scheme used to group together philosophical achievements that should be evaluated on their own terms anyway: a sort of generic appeal to revolutionary consequences that is a bit silly because anything revolutionary is unique by definition.

I don’t mean to say that we should avoid speculations; indeed, philosophy lives by speculating. It’s just that the projects that currently seem most interesting to me tend to take something from, say, at least two or three hundred years ago and project it into an indefinite future. On these time scales we can begin to see consequences that give us something to work with. Of course, current events will be a part of the narrative, but they are subsumed under the trajectory. Their importance will be determined by the act of projection. So if I were to end with proposing a maxim for how humanistic philosophers should approach their task right now, it would be to think about the human in the most inhuman terms we can imagine. Here, the lens of natural history seems far more potent than current events.

List of works cited by Olsson

Olsson, C. C. (2025) “Gymnastics and the philosophy of anti-planetary practice”. Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy 21(1), pp. 280-311. https://cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/view/1233

Olsson, C. C. (2025) “Naturalism and the self-effacement of the non-representational subject”. cultural geographies. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14744740251319033

Likavčan, L., Olsson, C. C. (2023) “Can artificial neural networks be normative models of reason? Limits and promises of topological accounts of orientation in thinking” in AI Theory in the Humanities. Models, Objects, Practices, Gross, R. and Jordan, R. (eds.). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, pp. 333-349. https://www.transcript-verlag.de/media/pdf/bc/05/b6/oa9783839466605.pdf.

Olsson, C. (2023). “Peak Face”, Urbanomic Document 0056. https://www.urbanomic.com/document/peak-face/.

Olsson, C. C. (2021). The Anthropocene conjecture and Wilfrid Sellars’ scientific image: (another) prolegomenon to rethinking the human?. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 103(2), pp. 103-115. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/04353684.2021.1891448

Works Cited

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987: 171-3.

- Sellars, Wilfrid. In the Space of Reasons: Selected Essays of Wilfrid Sellars. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Yusoff, Kathryn. Geologic Life: Inhuman Intimacies and the Geophysics of Race. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024.

- Negarestani, Reza. “Labor of the Inhuman.” In #Accelerate, edited by Robin Mackay and Armen Avanessian. Falmouth/New York: Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2014, 425-66.

- Negarestani, Reza. Intelligence and Spirit. Falmouth, UK/New York, NY: Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2018: 128.

- See Korsgaard, Christine M. Self-Constitution: Agency, Identity, and Integrity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

- Likavčan, Lukáš. “Another Earth: An Astronomical Concept of the Planet for the Environmental Humanities.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 25, no. 1 (2024): 17-36. Clark, Nigel, and Bronislaw Szerszynski. “What Can a Planet Do?”. cultural geographies (2025): 14744740251326904.

- Berlin, Isaiah. Two Concepts of Liberty. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1958.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcfp25LaWjI

- Gamez, Patrick. Posthumanism Meets Surveillance Capitalism: How to Delete the Manifest Image. Cham: Springer Nature, 2025.