Gabriele de Seta is, technically, a sociologist. He is a Researcher at the University of Bergen, where he leads the ALGOFOLK project (“Algorithmic folklore: The mutual shaping of vernacular creativity and automation”) funded by a Trond Mohn Foundation Starting Grant (2024-2028). Gabriele holds a PhD from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and was a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica and at the University of Bergen, where he was part of the ERC-funded project “Machine Vision in Everyday Life”. His research work, grounded on qualitative and ethnographic methods, focuses on digital media practices, sociotechnical infrastructures and vernacular creativity in the Chinese-speaking world. He is also interested in experimental, creative and collaborative approaches to knowledge-production (http://paranom.asia/about/).

DIFFRACTIONS: Your bibliography reads like a map of the internet’s evolution: from the folk cultures of early platforms to the algorithmic systems of today. As a digital anthropologist/researcher, what was the initial ‘entry point’ that compelled you? Was it a specific piece of digital folklore, a particular online community, or a theoretical puzzle about technology and culture that you felt was missing from the conversation? Secondly, an intriguing throughline in your work is the concept of replication, from the communal mimicry of memes to the automated generation of synthetic media. I’m fascinated by what draws a researcher to this continuum. Was it an initial interest in how culture copies itself that naturally led you to AI, or was it the rise of AI that reframed your earlier work on memes and folklore, revealing a deeper pattern?

Gabriele de Seta: This is probably more of an artifact of my life as a millennial – my first memories of the internet are the sounds of a 56k modem handshake and HTML websites from the early 1990s, so that’s why I am quite fond of those early folk cultures that developed when the term platform didn’t yet mean what it does today. I guess that my entry point into all of this has been my own experience and practice: I learned programming in HTML (and using DOS) as a kid working through some courses with my grandfather during summer holidays, and a few years later I coded the website for my Warcraft III clan. I spent years socializing on the discussion boards of hardware-related websites and music magazines, and eventually I became what in the 2010s we would call chronically online. Overall, I would say that Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied’s book Digital Folklore captured something fundamental that was missing from the conversation: the fact that all these experiences and practices were not just historical curiosities or nostalgia-fodder, but also – and more importantly – a fundamental component of social life. So yes, if you ask about a missing piece in the puzzle of technology and society, I would say that this was it.

More than replication, a throughline in my work is perhaps that of articulation. I think that from the animated GIFs of the early vernacular web and the viral memes of the 2000s to the more contemporary forms of algorithmic folklore and synthetic media, what really interests me is how significance and sociality are articulated by humans and computational systems. What draws me to this intuition is the fact that it is a precise balance of agency that is quite difficult to pinpoint precisely. It is much easier (and uninteresting, I feel) to argue that nothing new is happening, as humans have always articulated meaning out of signs, or that things are drastically different with technologies that can generate signification out of thin air. I am drawn to these difficult balances – and with the return of AI on the scene, this has obviously become even more challenging.

DIFF: You’ve proposed ‘synthetic ethnography’ and the use of ‘synthetic probes’ as new field devices for qualitative research. As you write, “Synthetic ethnography is not simply a participatory qualitative research methodology applied to the study of the social and cultural contexts developing around generative models but also strives to envision practical and experimental ways to repurpose these technologies as research tools in their own right.” Could you walk us through a concrete example of how you used a prompt or a ‘probe’ to generate data or an insight that traditional interviews or participant observation would have missed? What are the unique affordances and blind spots of making ethnography ‘synthetic’?

Also, I found an interesting term discussed in one of your co-written essays, the “latent walk” as a fascinating “analogy for working through assemblages of synthetic data” (Knuutila, 2023, p. 8). Could you elaborate on how that fits into your methodological schema?

GDS: I admit that adding ‘synthetic’ in front of other things is becoming a bit of a shtick in my recent work – I wrote about the need to discuss synthetic media as a new category of content rather than reducing it to specific vernacular categories like ‘deepfakes’ or ‘slop’, and it kind of snowballed from there. But I also appreciate how the term oscillates between the adjectival form (‘synthetic’ as used in the sci-fi imaginary of cyborgs and robots, but also in the existing domains of chemistry, material science or biology) and the more philosophical or literary concept of synthesis (without needing to limit it to dialectical materialism). I think it is a productive word today, particularly as these two usages clash and upend one another. Me and two colleagues (Matti Pojhonen and Aleksi Knuutila) came up with the idea of ‘synthetic ethnography’ a few years ago to describe a variety of approaches to immersive, participatory and dialogic qualitative research that are not simply ethnographic strategies applied to synthetic media, but rather new articulations of ethnography ‘fine-tuned’ for studying the sociotechnical assemblages that emerge around technologies like LLMs, generative AI, or automated agents.

The core idea that our approaches share is that – just as for other kinds of epistemological approaches inspired by the digital methods – it can be productive to use a technology to study the technology itself. If digital methods recommended to think about the “methods of the medium”, we are perhaps pushing towards figuring out what the “methods of the model” would be, in this case. In our work, this approach is embodied by specific tools or instruments, or “field devices” (something we borrow from the work of anthropologists Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella) which can be deployed in a research situation or even precipitate a research situation by themselves. The “synthetic probes” I propose in the article you mention are one example of field device. In very simple terms, I wanted to think through existing uses of probes (in medicine, space exploration, and even in ethnographic interviewing) in the context of machine learning models: how can we probe those?

Computer scientists have their own answers to this question, but I was trying to develop something less technical that did not require any special access to the model besides inference. The idea behind a synthetic probe is that you formalize a mechanism (which can be a prompt pattern, a type of image, a logical procedure, a jailbreaking trick, etc.) and ‘launch it’ into the model’s latent space in controlled conditions over many iterations, trying to map out something that happens inside the model by comparing the outputs. In my article I describe how I probed a specific model (ModelScope Text2Video) with a sequence of minimal prompts about China in order to map its representational repertoire, and ended up with around a thousand outputs that allowed me to describe some interesting findings.

For example, I was able to trace the videos produced to a specific training dataset (WebVid) which in turn was mostly scraped off the ShutterStock website, meaning that the aesthetic and representational decisions of stock image producers ended up determining how a text-to-video model depicts a country. These are very basic observations, but they would have not been possible by simply interviewing the model’s users or even the computer scientists behind it. In a way, this is quite close to what my coauthor Aleksi Knuutila describes as “latent walk” – in his case, he actually trains a model on Google StreetView images of London that are also mapped onto socioeconomic indicators, to then conduct virtual walkalongs with London residents, chatting about the GAN-generated images of the city and discussing their reactions to them. I think that we share an interest in figuring out how to rescale ethnography – a methodology that is traditionally sized to relatively small human groups and bounded social contexts – for the inhuman, multidimensional scales of machine learning and large datasets.

DIFF: Following up on your work ‘Latent China,’ you use the synthetic documentary as a methodological device to explore a model’s latent space. Given that the underlying ModelScopeT2V is itself an evolution of Stable Diffusion, how did its specific technical innovations directly shape the kinds of cultural or social ‘probes’ you were able to create, and what does this tell us about the relationship between a model’s architecture and the qualitative insights we can extract from it?

GDS: The idea of making a “synthetic documentary” was mostly a provocation driven by the hype around generative AI products promising to replace and automate creative production, but it really helped me approach the model with a purpose – having to produce a lot of video material about something as general as ‘China’ forced me to engage with the model over an extensive period of time, and to develop a procedure to move between prompts once I felt that one of them reached some kind of saturation. Obviously, the result is not a documentary, but again, most of the videos were likely generated from the abstraction of stock footage about China, so the border between genres is not that clear-cut. If one can make a documentary by patching together stock footage, what happens when you patch together machine-learned approximations of it?

As for your question about the sociotechnical history of this specific model: yes, ModelScope T2V is a diffusion model trained on at least three separate datasets (LAION5b, Imagenet, and WebVid), and combines multiple stages (text feature extraction, text feature-to-video diffusion, and latent to visual space video conversion). It is impossible to determine much about all of these datasets and components through synthethic probing. Even my conclusions about the WebVid dataset are partial, and mostly derived from a happy accident: the fact that most video outputs display an approximation of the ShutterStock logo, as the model has likely learned that this is one of the most prominent features in the training data. So I would say that a field device like the synthetic probe can get you a bit deeper than traditional ethnographic research (participant observation, interviews, etc.) or qualitative approaches to machine learning (such as content analysis, close readings, etc.), but it cannot get to the bottom of things – for that, you need to combine more approaches including code analysis, model archaeology, quantitative methods, and so on.

DIFF: You begin your essay China’s digital infrastructure: Networks, systems, standards by arguing that we must move beyond the dual narratives of the ‘Great Firewall’ and ‘triumphal governmental imaginaries’ to understand Chinese digital infrastructure. Using your own example of the Huawei C&C08 switch with its rat-proof mesh and rural focus could you elaborate on how this focus on the situated materiality of infrastructure, from a single cabinet to a global network, fundamentally changes our political and social understanding of China’s technological rise? Further, could you expand a bit on the networks, platforms, protocols, or standards that are specific or native to China’s infrastructural emergence?

GDS: Yes, I stand by that. I think that those are two extremes. One – the Great Firewall – is a much-mythologized assemblage of very real filtering systems, blacklists, censorship practices and management procedures. The other – China’s digital infrastructural imaginary – is a combination of vision, ideal, narrative, a discourse (as most imaginaries are). Both of these things are not all there is to infrastructure. In fact, infrastructure is precisely what happens in between these extremes. Something like the Great Firewall is definitely part of China’s digital infrastructure, but it is important to conceptualize and tease out this infrastructural status, which has also evolved historically from a mostly parasitic relationship with early internet development to a more constitutive role in actively shaping digital ecosystems. In another article (titled Gateways, sieves and domes) I try to examine China’s digital infrastructure through the stack model proposed by Benjamin Bratton, and the Great Firewall is the example I use to discuss “sieves”, infrastructural components that are nestled between layers, filtering and managing access to the usage vectors running between them.

I think it is important to work along these lines and not simply assume infrastructure to just be there or to be relevant by itself, but to actually take infrastructure as a method, if that makes sense – in other words, to examine how assemblages of materials, relationships, efforts and imaginaries come together into something that sustains an existing structure or props up a new one, which is what infrastructure ultimately means. The little exercise in the special issue introduction you mention is just a blueprint for this: I wanted to tell the story of an unassuming piece of network technology (the Huawei C&C08 switch) to show how infrastructure has some fractal properties: you can find traces of much larger developments in minute components, and trace back the origin of current developments and future imaginaries (such as Huawei’s leading position in global digital infrastructure) to seemingly trivial details (adding a rat-proof mesh to a cabinet). Rather than changing our political and social understanding of China’s technological rise, I guess this can at least help question broader “rise and fall” tropes, which are often just partial readings of deeper infrastructural dynamics and configurations.

For example, to answer your question about the networks, platforms, protocols, or standards that are specific China’s infrastructural emergence – there is countless of them! The early history of communication networks (from telegraph cables onwards) in China is fascinating, as is the genealogy of standards – Jack Qiu has written some very interesting pieces on TD-SCMA, for example, which was China’s alternative to 3G and one of the first successes in promoting a homegrown standard globally; I’ve looked into the various GB standards to encode Chinese characters on the web, which have shaped the history of vernacular creativity online; the special issue I edited has some more recent examples in the realm of self-driving cars and data encoding (the QR code). If we go into the realm of platforms, there is more than a decade of history to mine for important insights into how this operational model connects to infrastructuralization. Overall, I would say that the more you scratch the surface of what you think infrastructure is, the more you realize that infrastructuring is what matters, and it often undermines assumptions about the local and the global, the homegrown and the foreign, the cultural and the technical.

DIFF: Your co-written essay LET A HUNDRED SINOFUTURISMS BLOOM evokes Mao’s “Let a hundred flowers bloom,” a slogan that initially encouraged dissent but was followed by a crackdown. If we are to let “a hundred sinofuturisms bloom,” what are the fundamental tensions between them? For example, how does the state-sanctioned “China Dream” futurism of global dominance conflict with the critical, ecological sinofuturism of a author like Chen Qiufan, or the post-human sinofuturism of an artist like Lu Yang? How do they re-introduce concepts of “cyclical time”, “layered history”, or “compressed” time to create a uniquely Chinese relationship with futurity?

GDS: Me and Virginia Conn did (and continue to do) a lot of work on the conceptual articulations between China and the future – the more we delved into this topic, the more we realized that the most important contribution we could add to the debate was a plea to not close off this relationship. So, yes, to let a hundred sinofuturisms bloom without closing off any potential vector or overdetermining which articulations of the future have more legitimacy or purchase on reality. Obviously, we do not plan to crack down on these debates, we will try to stick to the “70% correct” part of Mao Zedong’s phrasing. I would say that the fundamental tensions between different articulation of China and the future reside precisely in how they seek to cut certain relationships: even state-sanctioned futurism (if there is such a thing) is not that simple – think of the crackdown on historical nihilism that seek to purify the past while the near future is bounded by nested goalposts (five-year plans, Made in China 2025, socialist modernization by 2035, etc.), or of how the “China scare” global dominance narratives contrast with Hu Jintao’s “community of shared destiny (or future) for humankind” concept that has become a Xi Jinping favorite.

The same applies to science fiction and contemporary art – there are several threads connecting techno-orientalist representations of Asia to modern critiques and recuperations of these aesthetics (think about ‘Chongqing Cyberpunk’ or Kowloon Walled City nostalgia theme parks); I also think that there are interesting overlaps and disjunctions between linear sci-fi futures and the more cyclical or recursive temporal logics of local genres like chuanyue, in which time travel to the past becomes an occasion to speculate about the possibility (or impossibility) of different presents. In short, I would be careful with simply attaching a “sinofuturist” label to whatever policy, imaginary, aesthetic or cultural product that combines China and the future, as their relationship might be articulated in very different ways.

DIFF: The article Imagining machine vision: Four visual registers from the Chinese AI industry argues that Chinese tech companies articulate a “cohesive” sociotechnical imaginary of machine vision through a limited set of visual registers. As you spell out, “These four registers, which we call computational abstraction, human–machine coordination, smooth everyday, and dashboard realism, allow Chinese tech companies to articulate their global ambitions and competitiveness through narrow and opaque representations of machine vision technologies.” Given the different company categories (tech giants, AI specialists, hardware manufacturers), where do you see the most significant points of tension or divergence in their imagined futures, despite the overall cohesion?

GDS: As I hinted above, sociotechnical imaginaries are quite specific visions of how technology and society interact. In the case of machine vision, China’s AI industry produces a relatively stable and consistent imaginary, which relies on multiple registers to articulate their vision. I wish I had more interesting findings here, but the truth is that this imaginary is quite boring! Our main finding was that the Chinese AI industry seems to be quite aligned with global aesthetic registers – the classic neon blue and green wireframes of brains and circuit boards, minimal consumer interfaces, comfy photos of active and satisfied users, and simplified representations of dashboards peppered with signifiers of efficiency and accuracy. Perhaps this non-uniqueness and global alignment is interesting in itself, as it demystifies – at least at the level of corporate aesthetics – the narrative about the Chinese tech industry having profound local characteristics or a distinct episteme. In fact, the main difference we noted was in the few companies that had pages dedicated to government contracts or social good endeavors, the aesthetics tended to veer towards a more official palette of reds and golds, relegating a certain vibe of cultural “Chineseness” to communications with the state. We did not see significant points of tensions or divergence between these companies, and their future imaginaries are quite trite.

DIFF: Finally, could you speak about your essay “Technologies of Clairvoyance Chinese Lineages and Mythologies of Machine Vision” featured in Machine Decision is Not Final China and the History and Future of Artificial Intelligence?

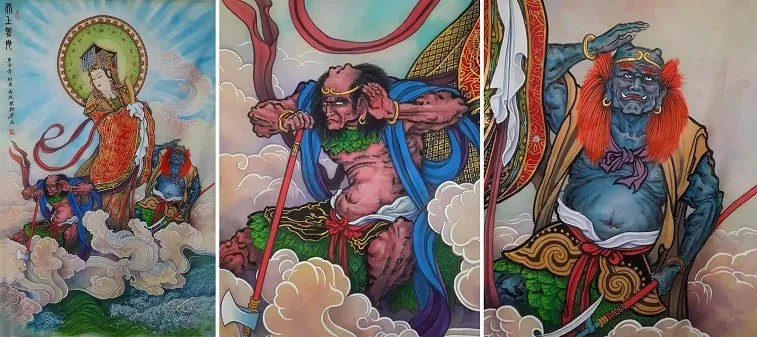

GDS: That chapter has been in the works for several years – I started writing a longer genealogy of machine vision in China, and only parts of it ended up in there. My idea was to look backwards in time and trace how machine vision connects not only to recent advancements in machine learning but also to modern technological development and ancient scientific discoveries. I center the chapter around the concept of “clairvoyance”, which in Chinese is translates as qianliyan (literally ‘thousand-mile eyes’) from the name of a guardian deity. I found it quite interesting that several commercial products – ranging from surveillance cameras to delivery robots – are also branded with this name (including a whole brand called QLYBot), as this points towards some rhetorical continuities between traditional and technological myth-making. Clairvoyance embodies a more-than-human kind of vision, capable of transcending distance and capturing details beyond what the eyes can see; this has obvious resonances in contemporary domains of technology like remote sensing, satellite imaging and computer vision, so I tried to sketch out a short history of the concept connecting the dots. The chapter also jumps forward in time to the arrival of the telescope via missionaries – a new optical technology that was called qianlijing, or ‘thousand-mile mirror’, testifying to the continued relevance of clairvoyance – and ends at the arrival of cybernetics in China via Qian Xuesen and other scientists who developed the foundations of contemporary optical automation. Overall, it is more of a sketch of a much larger project that I am still hoping to complete one day, but I think that it adds a useful perspective to the book.

REFERENCES

Conn, V. L., & de Seta, G. (2023). Let a hundred Sinofuturisms bloom. In The Routledge handbook of CoFuturisms (1st ed., pp. [ 1–11]). Routledge.

de Seta, G. (2023). China’s digital infrastructure: Networks, systems, standards. Global Media and China, 8(3), 245-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364231202203 (Original work published 2023)

de Seta, G., & Shchetvina, A. (2024). Imagining machine vision: Four visual registers from the Chinese AI industry. AI & Society, 39, 2267–2284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01733-x

de Seta, G. (2024). Synthetic probes: A qualitative experiment in latent space exploration. Sociologica, 18(2), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/19512

de Seta, G. (2025). Technologies of clairvoyance: Chinese lineages and mythologies of machine vision. In B. Bratton, B. Konior, A. Greenspan, & A. Ireland (Eds.), Machine decision is not final: China and the history and future of artificial intelligence (pp. 141–155). Urbanomic.

de Seta, G., Pohjonen, M., & Knuutila, A. (2024). Synthetic ethnography: Field devices for the qualitative study of generative models. Big Data & Society, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241303126 (Original work published 2024)

Knuutila A (2023) Generative models for visualising abstract social processes: Guiding streetview image synthesis of StyleGAN2 with indices of deprivation. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.00570